14 July 2012

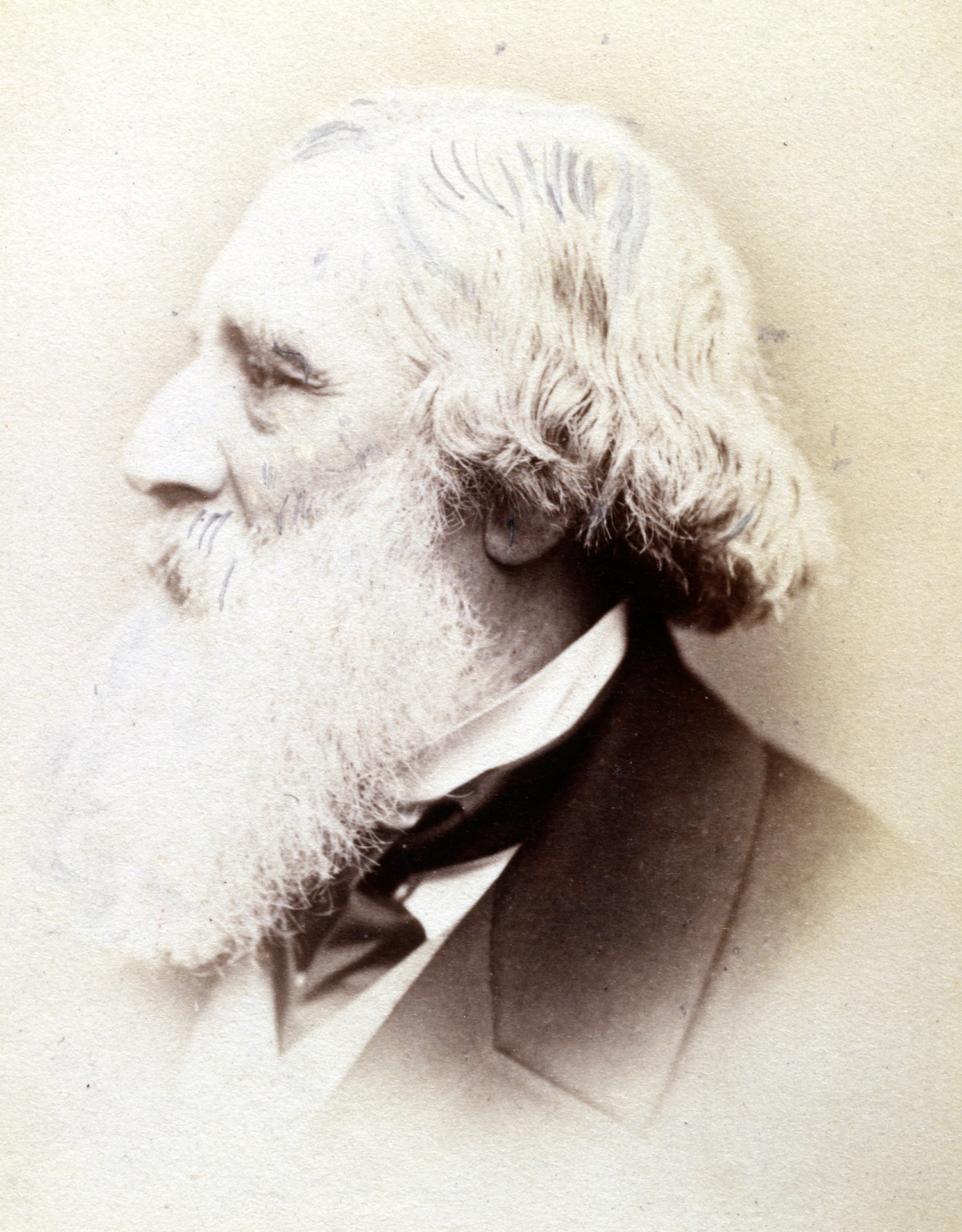

John Frederick Lewis, John Watkins (1864). Royal Academy Of Arts, London.

John Frederick Lewis, John Watkins (1864). Royal Academy Of Arts, London.

John Frederick Lewis is considered one of the most important British Orientalist artists of the Victorian era. Pera Museum exhibited several of Lewis’ paintings as part of the Lure of the East exhibition in 2008 organized in collaboration with Tate Britain.

In 1876, the year that John Frederick Lewis died, his fellow Royal Academician, Charles West Cope, exhibited a painting at that institution, entitled The Council of the Royal Academy selecting Pictures for the exhibition, 1875. Lewis, seated on the left, is one of a number of eminent Royal Academicians, including Sir Francis Grant, Sir Frederic Leighton and John Everett Millais, selected by Cope to represent the Academy at this time. It was, in the opinion of a later Secretary of the Academy, Frederick Eaton, “a very representative group of some of the principal members of the Academy at the time it was painted, in 1875, and most of the likenesses are excellent”, although this was not “a Council that ever actually existed – that is to say the members depicted never all served on the council together”. The painting shows Lewis in his public role as a distinguished member of the British art establishment of the mid nineteenth century, commensurate with the high standing he had achieved during a career of over a quarter of a century as the pre-eminent painter of meticulously observed and exquisitely rendered scenes of Oriental life. But in these paintings we can discern another, less orthodox, aspect of his life, a reference to the Oriental role that he had fashioned for himself. The tension between Lewis’s two personas – his conventional ‘Western’ face and a more outré ‘Eastern’ obverse – is worth exploring.

Caricature of John Frederick Lewis

Caricature of John Frederick Lewis

As his fellow artists well knew, the public role that came with the success of Lewis’s Oriental paintings did not sit easy on his shoulders. He was elected President of the Society of Painters in Water Colours in November 1855, but resigned little more than two years later. When required to make an official speech at a members’ dinner, he was tongue-tied: “I was all abroad – depressed & spiritless…. you have a President who whatever other qualities he may possess is evidently a very bad chairman”, he wrote next day to the Secretary. In February the following year, he resigned both presidency and membership of the Society, on the grounds of over-work: his watercolour methods were “so laborious & unremunerative, that I now find it imperative to pursue it in another & more lucrative material”. The strain of juggling his efforts between watercolour and oil, producing work for both exhibiting institutions, had become too much for him. Ambition dictated that oil should be preferred, prompting his decision to resign from the Water-Colour Society in order to manoeuvre himself into a better position for election to the Royal Academy, since the institution’s rules at this time precluded membership of another exhibiting society.

The artistic ‘club’ that Lewis joined when he was elected, in 1859 as Associate and in 1865 as full member, of the Royal Academy, does not seem to have been a milieu in which he felt at ease. Ruskin later noted this dislocation from convivial life: “There was something un-English about him, which separated him from the good-humoured groups of established fame whose members abetted or jested with each other. … He never dined with us, as our other painter friends did”. Nor did Lewis relish the obligatory teaching duties as a “Visitor” in the Painting School, where he was remembered by a student, William Silas Spanton, as “not a good teacher, being too fidgety, and particular as to materials”. His methods were too meticulous to encourage followers and he preferred to work alone away from the smoke and dirt of London, aided by his wife who is said to have “cleaned his brushes and set his palette”.

With this image of an aloof, unsociable Lewis in mind, apparently at a far remove from the dandified bon viveur of his younger days, the features of the Watkins photograph – craggy brow, large beaky nose and wary expression – which the “SEM” caricature brings more sharply into focus, construct an identity that seems aptly described, fifty years after his death, as “this solitary eagle”.

Interior of a Mosque At Cairo—Afternoon Prayer (The ‘Asr), 1857, Oil On Panel. Private Collection.

Interior of a Mosque At Cairo—Afternoon Prayer (The ‘Asr), 1857, Oil On Panel. Private Collection.

Public recognition and success in the market were undoubtedly of paramount importance to Lewis, and were goals that he actively pursued. His deliberate removal of himself and his wife away from the hub of artistic activity in London to the suburban seclusion of Walton-on-Thames, however, seems to indicate that contradictory impulses, propelling him towards a constructed public persona on the one hand and recoiling from it on the other, were at work within his personality. I would suggest that this dichotomy in Lewis’s life between the seeking and the shunning of the limelight is reflected in the disguised auto-mimetic representations that recur so frequently in his work.

Born into a prodigiously talented artistic family, Lewis was aware from a young age of the intensely competitive art market of early nineteenth-century London and the need to create an artistic niche for himself. An early pencil drawing, which shows him posing nonchalantly, with his two younger brothers behind, neatly encapsulates the dandyish persona that Lewis adopted as a young man. The consciousness of self that was invaluable for a young, ambitious artist is evident in the numerous self-portrait drawings that are also contained within this album of Lewis’s early drawings (Figs. 4 and 5). Like many artists before and since, Lewis used his own features to experiment with different poses as well as to communicate aspects of his self-image, adopting the practice later recommended by a younger contemporary, William Powell Frith. Although, like Frith, Lewis was probably aware that he was following established artistic tradition, his early self-portraits, unlike those of many other artists, did not enter the public arena, being made, it seems, solely for himself and his family.

An Arab of the Desert Of Sinai, John Frederick Lewis, 1858, Oil On Panel. Shafik Gabr Collection, Cairo

An Arab of the Desert Of Sinai, John Frederick Lewis, 1858, Oil On Panel. Shafik Gabr Collection, Cairo

Just as his career changed direction several times, so Lewis affected different personas at different times of his life, some of them conflicting, some complementary, reflecting the contrarities within his personality. Apparent non-productivity contrasts with painstaking attention to detail; the respected but aloof “great Oriental” was at the same time an uxorious husband; the extrovert dandy who loved extravagant clothes and frequented clubs was also an introverted seeker of solitude, with a nervous disposition. He was, as his younger contemporary, Baudelaire, wrote in 1863, “an ‘I’ with an insatiable appetite for the ‘non-I’”. Nevertheless, in a career that was punctuated by intermittent translocations, one of the unifying themes might be the representations of himself that extend from his boyhood to his venerable old age.

Extract taken from Briony Llewellyn’s article in The Poetics and Politics of Place.

Canadian artist Marcel Dzama shares five albums he listened to most frequently while preparing his exhibition Dancing with the Moon at Pera Museum. Spanning from post-punk depths to subtle folk tones, this list offers a glimpse into the sounds that shape his visual world.

Each memory tells an intimate story; each collection presents us with the reality of containing an intimate story as well. The collection is akin to a whole in which many memories and stories of the artist, the viewer, and the collector are brought together. At the heart of a collection is memory, nurtured from the past and projecting into the future.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)