20 April 2020

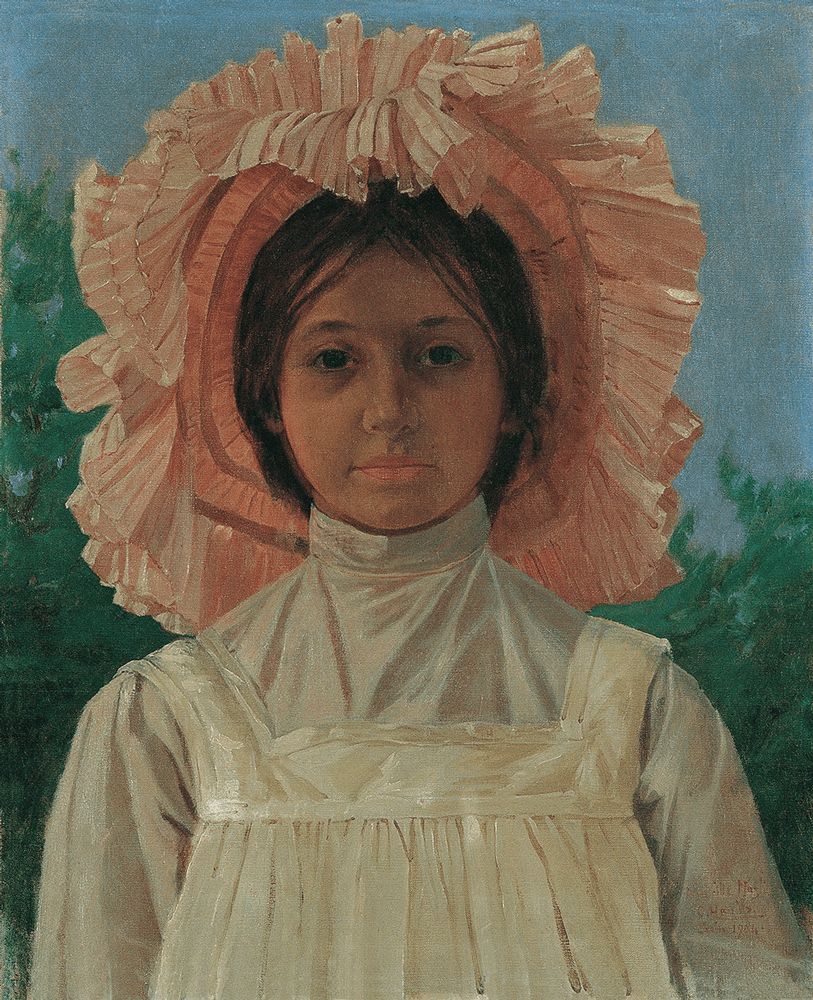

The Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation’s Orientalist Painting Collection includes two children’s portraits that are often featured in exhibitions on the second floor of the Pera Museum. These portraits both date back to the early 20th century, and were made four years apart. One depicts Prince Abdürrahim Efendi, son of Sultan Abdulhamid II, while the figure portrayed on the other is Nazlı, the daughter of Osman Hamdi Bey. Although Nazlı was only one year older than Abdürrahim, this fact is not immediately apparent to the observer, as Nazlı was 11 years old at the time of the painting, while Abdürrahim Efendi is seven in his portrait. Both children were born to their fathers in their fifties, and held a special place in their hearts. The portrait of Nazlı, the youngest child of Osman Hamdi Bey, was made by her father himself, and she was a popular subject in many of his other paintings. The portrait of the prince was made by Abdulhamid II’s court painter Fausto Zonaro at the Yıldız Palace. Both children grew up in an environment immersed in music and painting.

The Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation’s Orientalist Painting Collection includes two children’s portraits that are often featured in exhibitions on the second floor of the Pera Museum. These portraits both date back to the early 20th century, and were made four years apart. One depicts Prince Abdürrahim Efendi, son of Sultan Abdulhamid II, while the figure portrayed on the other is Nazlı, the daughter of Osman Hamdi Bey. Although Nazlı was only one year older than Abdürrahim, this fact is not immediately apparent to the observer, as Nazlı was 11 years old at the time of the painting, while Abdürrahim Efendi is seven in his portrait. Both children were born to their fathers in their fifties, and held a special place in their hearts. The portrait of Nazlı, the youngest child of Osman Hamdi Bey, was made by her father himself, and she was a popular subject in many of his other paintings. The portrait of the prince was made by Abdulhamid II’s court painter Fausto Zonaro at the Yıldız Palace. Both children grew up in an environment immersed in music and painting.

Born in August 14, 1894 to Abdulhamid II and Peyveste Hanım, Prince Abdürrahim Efendi grew up to be a decorated soldier, and his childhood portrait depicting him in an artilleryman’s uniform can be taken as a foreshadowing of his future life. In 1908, Abdürrahim enrolled at the Mühendishâne-i Berrî-i Hümâyun (Imperial School of Military Engineering) that trained military engineers and artilleryman. He went on to join the Mekteb-i Harbiye (Military Academy) in 1910, graduating in 1912. From 1914 to 1916, he trained in Germany in the first regiment of Wilhelm II as an artilleryman first lieutenant, and continued his military service in the World War I as a colonel and regimental commander. Fluent in German and French, Abdürrahim Efendi was skilled in music and played the piano, mandolin and cello. An avid painter as well, he gifted one of his oil paintings to Victor Emmanuel III, heir to the Italian throne, during the latter’s visit to Istanbul. (<http://www.erolmakzume.com/wp/?p=3087>). Similar to his interest in the military, Abdürrahim was enthusiastic towards painting at the time his portrait was made, as evident from Zonaro’s account:

“One day, Chamberlain Emin Bey relayed to me that the Sultan wanted me to create a painting of his youngest son: A little artilleryman…

The prince in question was no other than Abdürrahim Efendi, who would later accompany his father into exile on Thessaloniki. He was yet to grow over a meter tall, but he was in a true officer’s uniform, complete with spurred boots, a sword and military decorations adorning his chest.

It proved to be a difficult task to draw him, because he would not sit still for even five minutes. He often had me worried by attempting to paint on the canvas I was working on. These were small acts of mischief characteristic of a young prince that were so often tolerated by their teachers in Oriental cultures. What did I do? I took care to prevent his brush from touching the head of the figure on the canvas.

I took the opportunity to make two paintings of the prince. I would work on one, making corrections and repainting it, and copying the work on the second. Of these two, one was hanged in the harem, and the other in one of the Sultan’s chambers in the selamlik. (Zonaro 2008: 220-221).”

Nazlı was born in September 4, 1893 as the youngest child of the French Naile (Marie) Hanım and Osman Hamdi. She grew up in a warm family environment, spending her time between her family’s mansion in Kuruçeşme and their summer villa in Eskihisar. The guestbook she kept from 1907 to 1911 provides accounts of the family members in their household as well as those of artists, diplomats, archeologists and aristocrats who visited Osman Hamdi Bey and were part of his circle of friends. In 1912, Nazlı married a diplomat, Esad Cemal Bey, with whom she had a daughter, Cenan (Sarç). She divorced and later married a French engineer in Paris named Audoin Fouache d’Halloy.

The artists who created the portraits of Prince Abdürrahim Efendi and Nazlı, the latter of which came to be known as “Girl with Pink Cap”, namely Fausto Zonaro, the Italian “ressam-ı hazret-i şehriyari”, or court painter, of Abdulhamid II, and Osman Hamdi Bey, director of the Müze-i Hümayun (Imperial Museum) and Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi (Academy of Fine Arts), a painter, archeologist and curator, were two of the most prominent artists in the culture & art community of late 19th century to early 20th century Istanbul. The two established a friendly relationship beginning from Zonaro’s early days in Istanbul, and went on to assume similar, pioneering roles that shaped the artistic environment of westernalization. Osman Hamdi was reported to be one of the famous visitors of Zonaro’s house in Akaretler, as well as a prestigious guest at the opening of the Italian painter’s exhibition in 1908 (Makzume 2004: 48, 59).

The artists who created the portraits of Prince Abdürrahim Efendi and Nazlı, the latter of which came to be known as “Girl with Pink Cap”, namely Fausto Zonaro, the Italian “ressam-ı hazret-i şehriyari”, or court painter, of Abdulhamid II, and Osman Hamdi Bey, director of the Müze-i Hümayun (Imperial Museum) and Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi (Academy of Fine Arts), a painter, archeologist and curator, were two of the most prominent artists in the culture & art community of late 19th century to early 20th century Istanbul. The two established a friendly relationship beginning from Zonaro’s early days in Istanbul, and went on to assume similar, pioneering roles that shaped the artistic environment of westernalization. Osman Hamdi was reported to be one of the famous visitors of Zonaro’s house in Akaretler, as well as a prestigious guest at the opening of the Italian painter’s exhibition in 1908 (Makzume 2004: 48, 59).

According to Zonaro’s memoirs, Osman Hamdi visited Zonaro in March 1906, to ask him to create works to be showcased at the Turkish pavilion at the International Monaco Exhibition. The Italian artist had been living in Istanbul for years, and in time, he had embraced an Ottoman lifestyle and became a prominent representative of the cosmopolitan cultural and artistic community in the city. Although reluctant at first, upon further thought, he did grant the request: “What was I to do? How was I to be part of the Italian pavilion anyway?” (Makzume 2004: 53; Zonaro 2008: 314). Although they hailed from different nations, the two artists were favorably disposed towards representing the same culture on the international community. Their paths had taken them, in different stages of their lives, to Paris, a beating heart of European Art where they kept abreast of developments in the art world.

Both painters created works for the first exhibitions in this cosmopolitan artistic community of Istanbul, and assumed important roles in art education. Osman Hamdi became the director of the country’s first school of fine arts, Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi, and contributed to the development of an arts education in the Western style. Zonaro did the same as a trainer in the painting workshop he ran at night in Parmakkapı, Beyoğlu, which, he claimed, he had opened for three Ottoman Greek students who dropped out of Sanayi-i Nefise, whose commitment to learn, he thought, should not be left unanswered (Zonaro 2008: 120-121).

Zonaro also recounts how he came to meet Osman Hamdi before being appointed as a court painter. The two were introduced by the renowned harpist Cervantes, who was in Istanbul at the time working as a tutor for the harems of mansions:

“Among his pupils was the daughter of the Turkish painter Hamdi Bey, a man of considerable wealth as the discoverer of what he claims to be the sarcophagus of Alexander, a curator, an advisor to Düyûn-ı Umûmiye (Ottoman Public Debt Administration) and many similar roles.

Hamdi Bey was enthusiastic about meeting prominent guests of the royal court and inviting them to his house or office. He was married to a French actress, and was a polite and sincere man. He frequently hosted parties at his mansion in Kuruçeşme. It was Cervantes who introduced me to Hamdi Bey. I found him to be a courteous and artistic individual who was quite familiar with Paris, where he spent many years. He displayed a wealth of knowledge as he talked about anyone or anything. He was curious to see my paintings. I had some of them brought to his home. He gave me hope towards many things, yet I had only placed my trust on myself. I graciously accepted his promises, and courageously walked on the path my heart guided me (Zonaro 2008: 62).”

While it is not possible to glean when exactly this took place from the memoirs of Zonaro, who arrived in Istanbul in 1891, it is apparently in the earlier stages of his career in the city where he was still trying to establish a following and promote himself and his works. Osman Hamdi Bey’s daughter mentioned by Zonaro is probably Leyla, Nazlı’s older sister born circa 1880.

Zonaro relates another event from his early years in Istanbul, where he attracted a crowd while painting a picture of open-air barbers working around the New Mosque. The crowd, in turn, attracted police officers, who took the painter responsible for the commotion to the police station. There, Zonaro told the pasha in charge that he was friends with almost every European ambassador and that he personally knew the museum director Hamdi Bey as well as the First Secretary to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Münir Bey, upon which he was released and given express verbal permission to create his art anywhere in the city, with the exception of Eyüp and the neighborhoods surrounding the palace (Zonaro 2008: 83).

The Italian painter mentions that he paid frequent visits to keep his relations close, which included occasionally joining Hamdi Bey at his mansion in Kuruçeşme. In one such visit, he found Osman Hamdi “with another prominent Turk” setting up fishing poles, and Osman Hamdi invited the painter to join them on a fishing trip to take advantage of the Atlantic bonito migration up the Bosporus. Two days later, as they returned on their boat to the mansion, Hamdi Bey asked “Do you figure we caught enough?” to which Zonaro, a novice fisherman at best, replied: “Enough to feed the entire population of Taksim.” He recounts that he barely managed to carry his share of the catch back to his home, gave some away to his neighbors, and that fish preserved in salt was the main course at his home for an entire week (Zonaro 2008: 78-79).

Osman Hamdi Bey died in February 1910, and the Italian painter Zonaro, 12 years his junior, returned to his country with his family one month later, as the government was changed and he was discharged from his position as court painter (Makzume 2004: 65).

The portraits of two children from the early 20th century serve as windows to their time; what we see through these portraits shed a light to the late 19th century to early 20th century with the similarities and differences in the lives of the children portrayed in them and the intersecting lives of the painters.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

CEZAR, Mustafa. Sanatta Batı’ya Açılış ve Osman Hamdi,Erol Kerim Aksoy Kültür, Eğitim, Spor ve Sağlık Yayını, İstanbul, 1995.

ELDEM, Edhem. Osman Hamdi Bey Sözlüğü, Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, İstanbul, 2010.

ELDEM, Edhem. Nazlı’nın Defteri, Osman Hamdi Bey’in Çevresi, Homer Kitabevi, 2014.

KIBRIS R. Barış (ed.). Osman Hamdi Bey, Bir Osmanlı Aydını. Pera Müzesi, İstanbul, 2019.

MAKZUME, Erol. “Doğumunun 150. yılında Osmanlı Saray Resamı Fausto Zonaro”, Doğumunun 150. yılında Osmanlı Saray Resamı Fausto Zonaro, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, İstanbul, 2004, 31-69.

RİFAT Samih, Barış KIBRIS ve Begüm AKKOYUNLU, ed. İmparatorluktan Portreler, Pera Müzesi, İstanbul, 2005.

ZONARO, Fausto. Abdülhamid’in Hükümdarlığında Yirmi Yıl, Fausto Zonaro’nun Hatıraları ve Eserleri, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, İstanbul, 2008.

1638, the year Louis XIV was born –his second name, Dieudonné, alluding to his God-given status– saw the diffusion of a cult of maternity encouraged by the very devout Anne of Austria, in thanks for the miracle by which she had given birth to an heir to the French throne. Simon François de Tours (1606-1671) painted the Queen in the guise of the Virgin Mary, and the young Louis XIV as the infant Jesus, in the allegorical portrait now in the Bishop’s Palace at Sens.

This life-size portrait of a girl is a fine example of the British art of portrait painting in the early 18th century. The child is shown posing on a terrace, which is enclosed at the right foreground by the plinth of a pillar; the background is mainly filled with trees and shrubs.

In a bid to review the International System of Units (SI), the International Bureau of Weights and Measures gathered at the 26th General Conference on Weights and Measures on November 16, 2018. Sixty member states have voted for changing four out of seven basic units of measurement. The kilogram is among the modified. Before describing the key points, let us have a closer look into the kilogram and its history.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)