29 July 2022

A unique collective, SUPERFLEX was established in 1993 by Jakob Fenger, Bjørnstjerne Christiansen, and Rasmus Rosengren Nielsen. There is a reason they call themselves an “expanded collective.” Apart from their artistic work processes, SUPERFLEX has consistently worked with a diversity of collaborators, from gardeners to engineers, architects to sociologists, from artists to audiences.

Suggesting alternative models for new social and economic systems, SUPERFLEX works appear before us as energy systems, beverages, sculptures, copies, hypnosis sessions, infrastructure, paintings, plant nurseries, contracts, or specifically designed public spaces.

In recent years, the most striking of their works has been the projects they engaged in for Superkilen. The meeting-place called Superkilen is where different ethnic groups living in the neighborhoods of Denmark can participate in a platform that encourages interaction between people beyond their different ethnic backgrounds, religions and cultures. Working in or outside of the customary physical exhibition location, SUPERFLEX continues in the realization of major public space projects in the region following its Superkilen enterprise, which opened in 2011. It is generally local communities, specialists and children that participate in these projects that are based on the concept of collaboration, but opposing public entities are also often brought together to suggest alternatives to relations between human beings and non-human forms. While defining the concept of community as “interspecies,” the collective works on the common urban landscape of humans, plants and animals. The projects for which the collective has so far suggested new public entities gives us an idea of the times and of the sociopolitical issues of the region.

Another subject that SUPERFLEX tackles is the act of copying. Copying can be identified under the keywords creativity, intellectual property, copyright, law, art, originality, and the economics of fakes and copying. In this article, we will speak of some of the work SUPERFLEX does in this context.

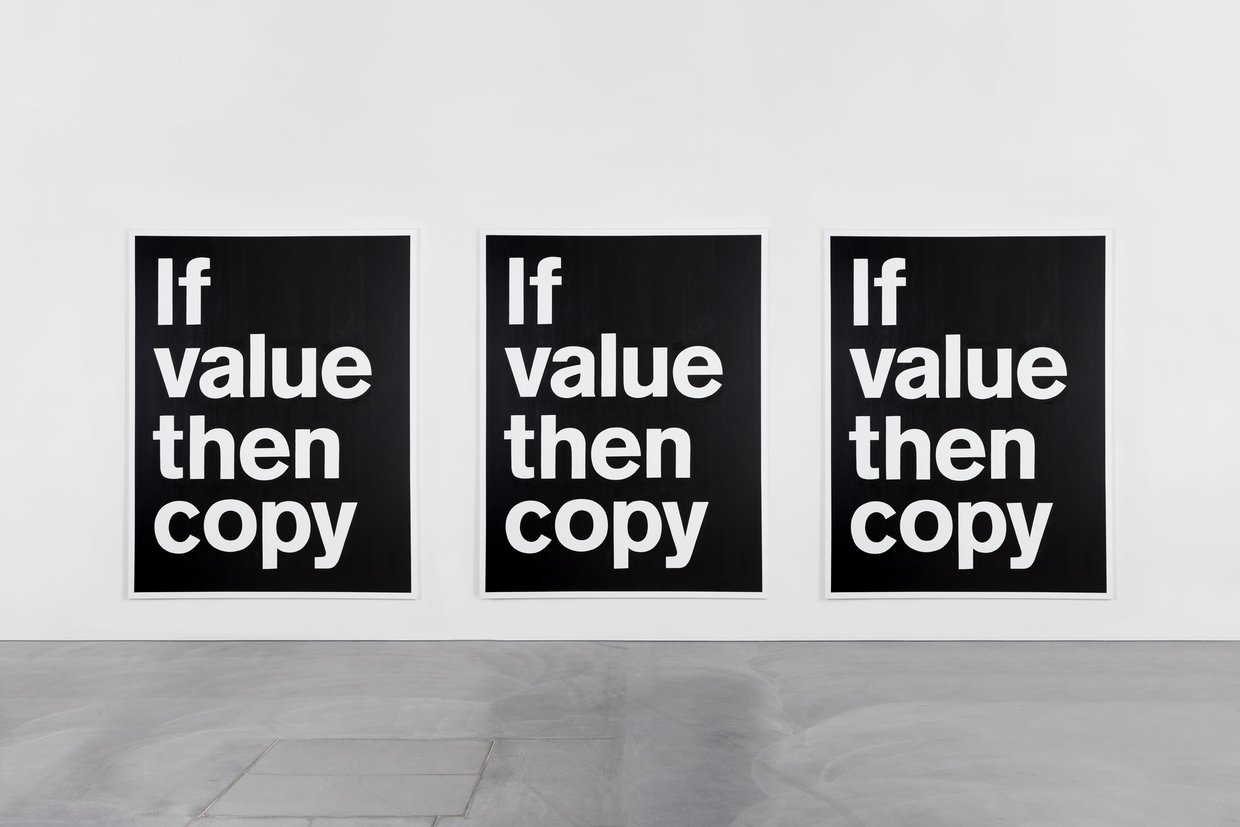

If Value Then Copy, 2017. Photo: Nils Stærk

If Value Then Copy, 2017. Photo: Nils StærkThe work of SUPERFLEX in collaboration with Copenhagen Brains, If Value Then Copy, which is what they define as a text painting, represents a slogan that questions the rights to nonmaterial works and ideas. Referring to the dictum, “If value then right” and consisting of three separate paintings, this work points to the uniformity of commercial mass production, challenging in effect the concepts of originality, authorship and value. In the spectrum of our everyday life reaching up to the area of creativity, how can we know whether any idea is actually original? Can a person demand property ownership of goods that are nonmaterial? If we don’t imitate what surrounds us and copy it, how can there be evolution?

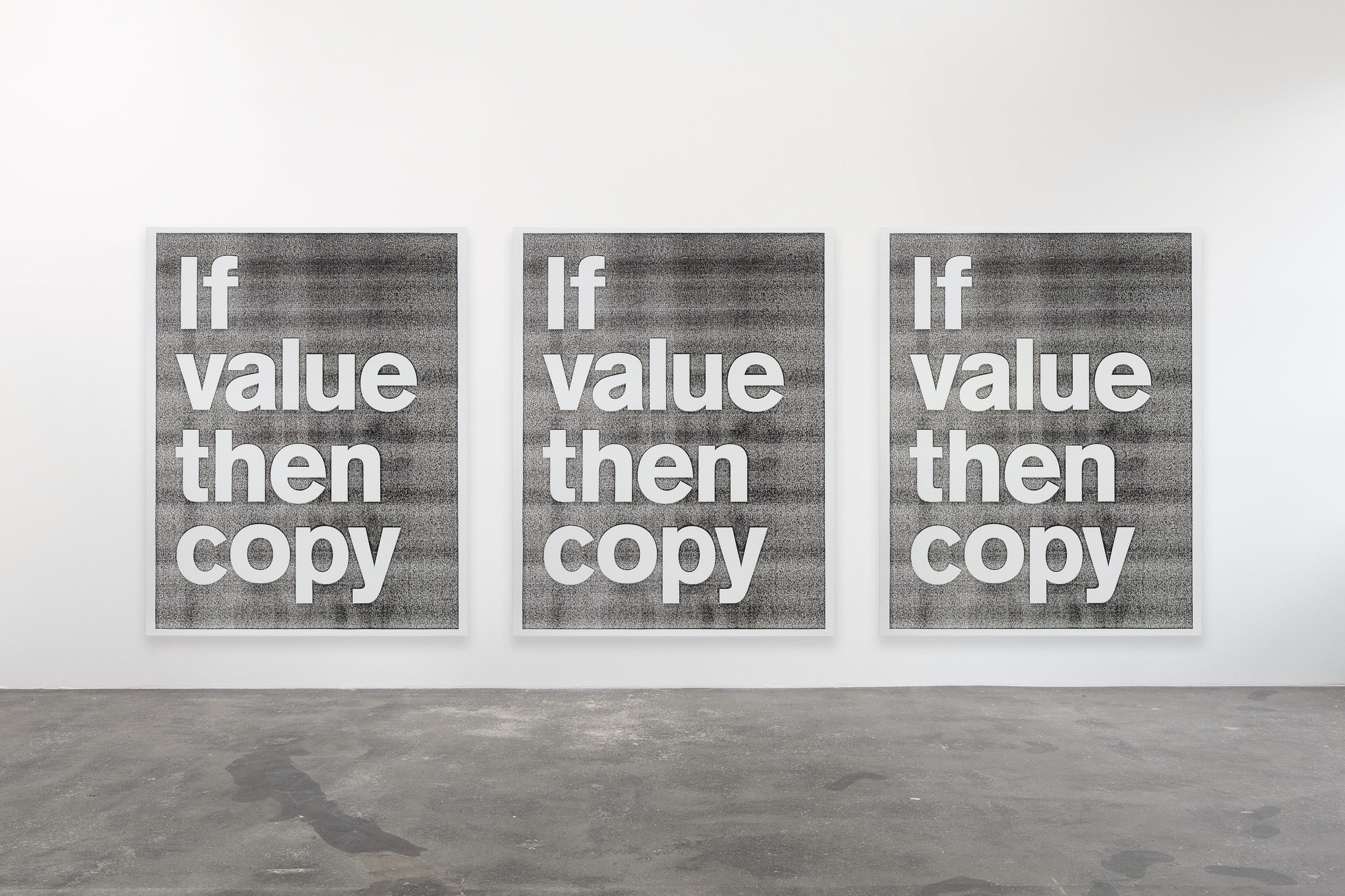

Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007. Photo: Nils Stærk Gallery

Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007. Photo: Nils Stærk Gallery Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007 installed at Fundación Jumex, Mexico City, 2013. Photo: SUPERFLEX

Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007 installed at Fundación Jumex, Mexico City, 2013. Photo: SUPERFLEX Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007. Photo: Nils Stærk Gallery

Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007. Photo: Nils Stærk Gallery Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007. Photo: Nils Stærk Gallery

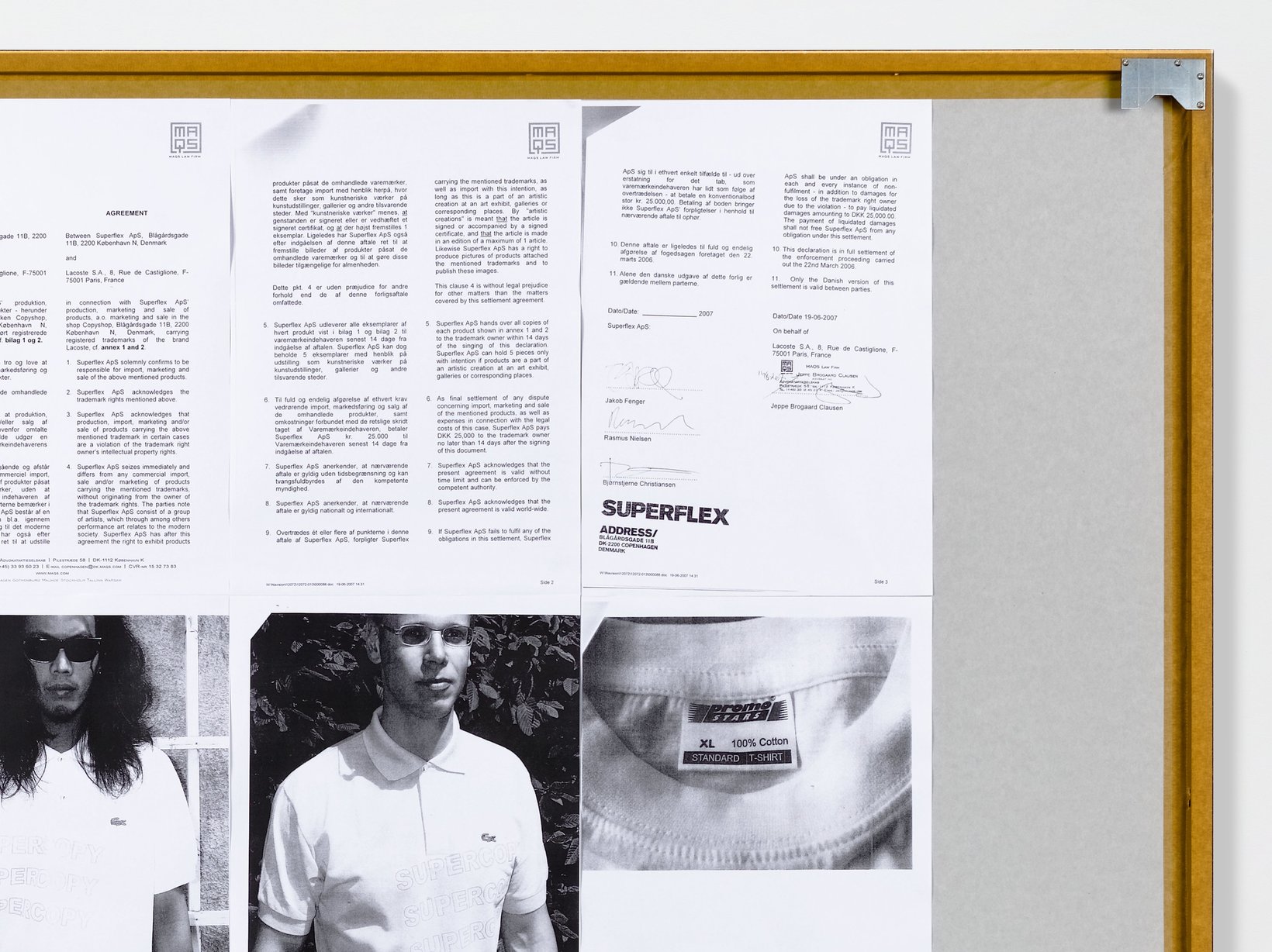

Supercopy/Lacoste (blackout), 2007. Photo: Nils Stærk GalleryAnother endeavor of SUPERFLEX that challenges the concept of intellectual property rights is Supercopy/Lacoste. The collective used screenprinting to print the word “SUPERCOPY” on the knock-off Lacoste t-shirts it procured from the Thailand market. Lacoste subsequently took legal action against SUPERFLEX for violation of copyright and trademark infringement in Denmark. After the litigation process, nine documents representing the legal agreement between SUPERFLEX and Lacoste were added to the backs of the photographs. The work consists of the photographs of the persons wearing the t-shirts and the legal papers.

Today, fakes/copies of many brand products sold at exorbitant prices are both manufactured and bought. The economics of copying provides thousands with jobs and its effects have a great impact on the social, economic and daily life of especially people in the Far East. Supercopy/Lacoste not only calls attention to the economics of copying and its magnitude, but also invites the viewer to think about the desires and habits of consumers.

In its work Free Beer, in which SUPERFLEX reflects on the relationship between economics and intellectual property rights, the word “free” is a reference to “Free Speech,” not to be confused with “cost-free.” This concept was inspired by the free software activist Richard Stallman, who is known for saying, “‘Free software’ is a matter of liberty, not price.” The work proposes a counter-system to the contemporary system of copyright. Collaborating with the students of Copenhagen IT University, the Collective produced a beer that they called Vores (Our Beer). The recipe and branding elements of the beer are accessible for use by everyone under the Creative Commons (Attribution-ShareAlike 2.5) license. Free Beer has been brewed in a variety of breweries, workshops and kitchens all over the world, including in Taipei, Sao Paolo, Los Angeles, Munich, Knoxville, Lausanne, Cornwall, Bolzano and Auckland, with or without the participation of SUPERFLEX.

This time, Free Sol LeWitt is a project in the form of a workshop whose concept derives from a quote from the artist: “I believe that ideas, once expressed, become the common property of all. They are invalid if not used, they can only be given away and not stolen.” The project is a workshop that produces copies of Sol LeWitt’s work Untitled (Wall Structure), 1972. The copies are metal replicas of the 1972 work and are distributed to the public. These production and distribution processes open up for discussion the controversial matter of the relationship between intellectual property rights and art. At the same time, Free Sol LeWitt is a reminder of how much the works of art exhibited in museums, those that are branded “cannot be copied” or “unique,” are so sterile and so detached from everyday life. Consequently, this reminder leads us to ask the following questions: What would the function of museums be if works of art were copyable and not unique? What would it mean for museums to own copyable works of art? What would actually be owned in such a case?

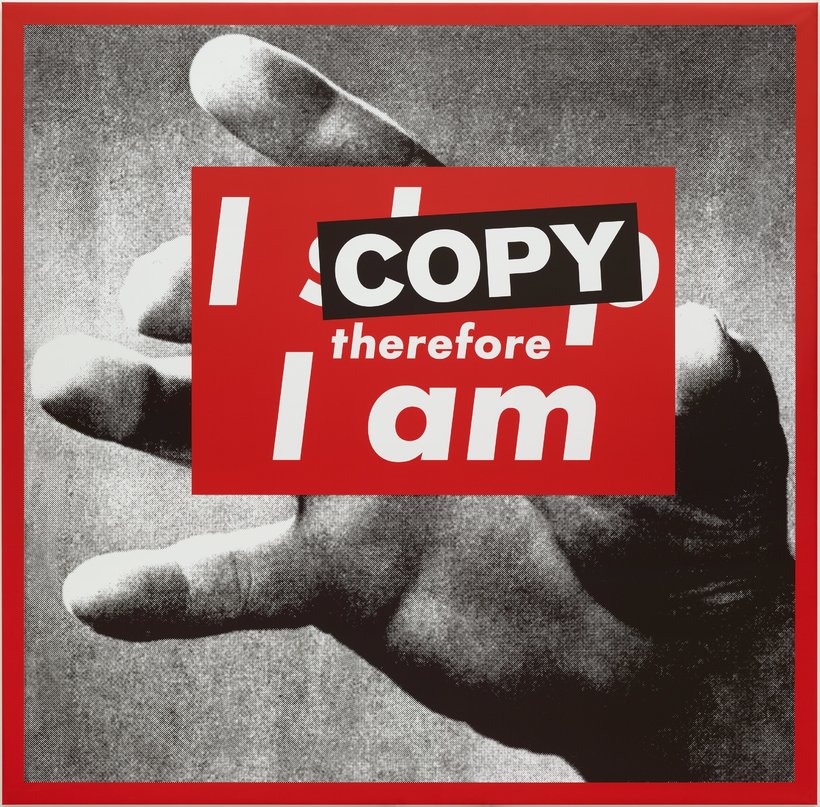

I Copy Therefore I Am. Everything put forward today that has been copied and owned by different minds amid all the possibilities holds its own uniqueness. Each new piece of information or data copied into a separate existence at different times and in different spaces creates its own originality. Can we then think of the project by SUPERFLEX titled I Copy Therefore I Am in the same way as we pondered the Free Sol LeWitt project?

The collective this time has turned the iconic anti-consumerism message created in 1987 by the artist Barbara Kruger, Untitled (I shop therefore I am) into a work called “I Copy Therefore I Am,” producing a statement against copyright. The project recreates Kruger’s work as it points to the political and philosophical aspects of copyright laws. While Kruger used Descartes’ famous quote to produce a critique of consumerism, the version by SUPERFLEX provides an existential statement: we are what we copy.

SUPERFLEX’s “I Copy Therefore I Am” project exhibited in And Now the Good News: Works from the Nobel Collection exhibition between April 13 - August 7, 2022 at the Pera Museum.

Coffee was served with much splendor at the harems of the Ottoman palace and mansions. First, sweets (usually jam) was served on silverware, followed by coffee serving. The coffee jug would be placed in a sitil (brazier), which had three chains on its sides for carrying, had cinders in the middle, and was made of tombac, silver or brass. The sitil had a satin or silk cover embroidered with silver thread, tinsel, sequin or even pearls and diamonds.

Inspired by the exhibition And Now the Good News, which focusing on the relationship between mass media and art, we prepared horoscope readings based on the chapters of the exhibition. Using the popular astrological language inspired by the effects of the movements of celestial bodies on people, these readings with references to the works in the exhibition make fictional future predictions inspired by the horoscope columns that we read in the newspapers with the desire to receive good news about our day.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)