06 August 2023

Isabel Muñoz is a Spanish photographer renowned for her captivating monochromatic portraits of individuals and cultures from around the world. Her works have been widely exhibited in numerous galleries and museums globally. One of the primary reasons why Muñoz's photography holds international significance is her exceptional ability to encapsulate the essence and aesthetics of diverse cultures through portraiture. Her photographic oeuvre typically depicts individuals from marginalized and traditional communities, thus emphasizing the unique ways of their lives while perpetuating their cultural heritage for posterity. Muñoz's artistic and technical acumen is outstanding and permanently contributes to the significance of her work. Her mastery of light and shadow, coupled with her ability to capture her subjects' emotional depth through facial expressions and body language, renders her portraits not just as mere representations but also as artistic expressions that reflect human experience. Furthermore, Muñoz's work has garnered accolades such as the National Photography Award in Spain and the Hasselblad Foundation's International Award in Photography, among others. Her works have also been exhibited in significant global exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale and the International Center of Photography in New York. She is being introduced to Türkiye’s art audience with a solo show at Pera Museum concentrating on three archeological sites: Göbeklitepe, Karahantepe and Sayburç. We had a conversation with Muñoz, who is engaging in this type of archaeological work for the first time in her career, about her practice, life path, her understanding of photography and the new exhibition.

You were born in Barcelona in 1951, then moved to Madrid in 1970 where nine years later, you registered at PhotoCentro to completely dedicate yourself to professional photography. After several years in the press and advertising sector, you returned to Madrid where you opened your first solo show: Toques. This began art career if I’m correct. Could you please share with us the story of your first exhibition and how your career in photography continued after that?

The field of photography in Spain has undergone significant changes over the years. During the 1970s, PhotoCentro was the only establishment dedicated to photography. One little-known fact about me is that during this time, I was married and had twins. As a photographer, I spent my summers in the United States studying photography because I had a strong desire to learn more about my profession. I have always been driven to seek new knowledge and experiences.

My first solo exhibition, Toques, which translates to Touch in English, was an essential event in my career. I chose this title because I believe that touching things - not only with my hands but also my eyes and heart - is crucial to my artistic process. The exhibition was held in the French Institution, which, at the time, had an atypical gallery space: The infirmary of the institution, complete with white tiles. During this exhibition, I was experimenting with new techniques such as platinum prints, cyanotypes, salted paper prints, and others.

I even have a humorous memory from the exhibition. One day, a piece was stolen, and everyone was alarmed. I reassured them, saying, "Please don't worry. If someone took the time to steal a piece, that means they loved it. They can have it, and I'm pleased they do." Additionally, I will never forget the memory of my dear grandmother climbing the stairs of the institution to attend my show. Some memories stay with you forever.

Your artistic vision is filled with a willingness to assert your ideas. Tango and Flamenco (1989) is considered the starting point of your unremitting search for the sentiments and emotions of humans in an attempt to capture the expressions of beauty within the human body. Your camera allows us to move in very close to your subjects, closer than we would permit ourselves. This should originate from your curiosity. I wonder the sources of this curiosity, what are the origins of your interest in Ethiopian tribal members, Brazilian Capoeira dancers, Iranian protagonists, African minorities and so on?

As human beings and professionals, we make evaluations. However, certain aspects of ourselves, such as our ways of loving and feeling, remain constant even as we change the way we express them. In my search for origins, I turned to tribal communities. When I first encountered the tribes in Ethiopia, I felt a connection to our shared heritage. I wanted to see how people lived in these places, how they dressed, and how they interacted with nature. Through art, I can convey not only the challenges that these tribes face but also the importance of Universal Human Rights. I discovered that I could use dance and the body to tell stories about ourselves and our cultures.

Regarding shyness in front of the camera, I find it to be a magical moment. It could either be a person or an object, as I also believe in the magic of nature and objects. I need to be close to the subject, both physically and emotionally. I have to love the subject. Over the years, I have learned that when someone feels loved, they give from themselves. In photography, there is no generosity, but rather love. If the person in front of the camera gives themselves to the camera, the moment becomes magical. There is no shyness in that moment, only respect. Photography cannot exist without respect, and if you love, you must respect. It is an integral part of the process.

Trance’n’dance was your first major exhibition (in Belgium). In the press, it was reported as “a journey into the visual world of an artist who is sometimes called a ‘body portraitist.’” The practices and rituals you have observed in the four corners of the world were the theme of your exhibition. How do you feel when you are identified as a “body portraitist”?

I have a personal dislike for names, as I believe they can be limiting. Instead, I prefer to use the body as a means of expression. At times, I also incorporate dance to communicate other ideas. I consider myself more of a storyteller, using various forms of art to convey messages.

How do you approach your subjects, and what do you hope to capture in your photography?

I strive for my photography to serve a purpose and tell a story with every image. I believe in the power of the visual medium and that art can communicate many things, including life and beauty. It brings me great satisfaction to think that my photography can be a support for people in different ways, and I hold this belief dear. If I ever feel like my photography fails to evoke emotions or give voice to a story, I feel the need to make a change and create something that serves society. Art is a fundamental part of life, like a guiding light that helps us navigate through the darkness.

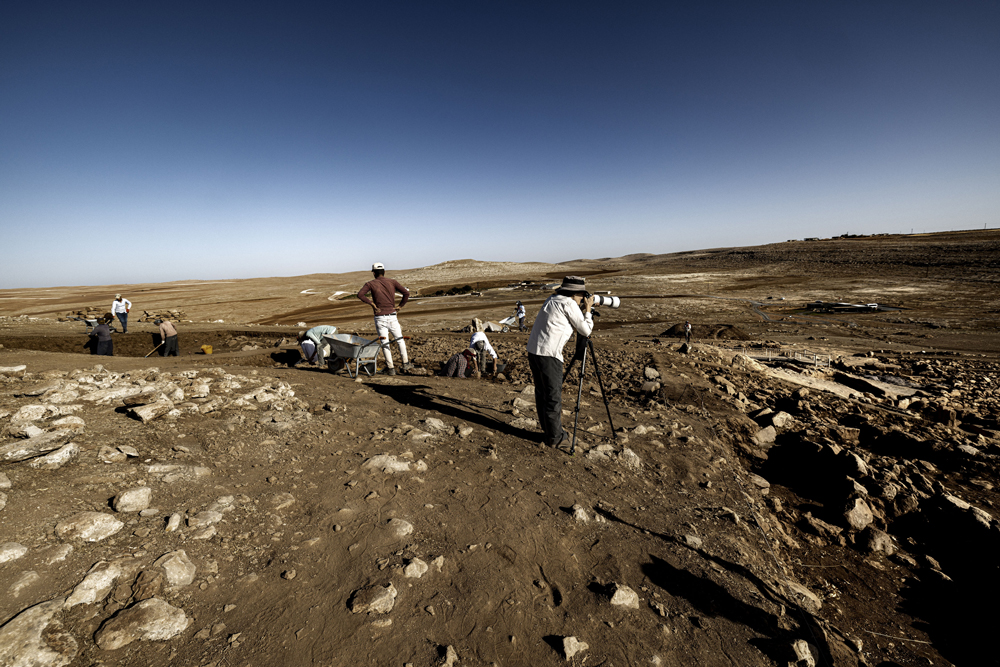

This time in Turkey, I had the opportunity to work with archaeologists for the first time, and I found their perspective on the importance of their discovery fascinating. They shared with me their dedication to understanding the past and working for the future, for the betterment of society. This mindset resonates with me as a photographer, as I strive to create work that allows people to connect and share experiences.

Your artistic creation made me think about the concept of “image.” The audience could understand what your works mean once they interpret the imagesIn his book titled What do pictures want? The Lives and Loves of Images . W. J. T. Mitchell asks what images “want” instead of asking what images “do”, and adds that “Because I wanted to turn power into desire. I turned a dominant model of power to be opposed into a model of innocence to be investigated or invited to speak out.” What is your opinion on that power and desire antagonism?

You are absolutely right. In my work, I see images in every human being, in music, and even in literature. When it comes to photography, it's not just capturing a moment, it's capturing a piece of something significant, like a ceremony or an event. It's like those beautiful Ottoman cemetery stones, they are not just lifeless objects, they have a story to tell, and they are alive in a sense.

I have a problem with the concept of power. I believe in desire and the connection between the artist and the viewer. It's not just about what the artist wants to convey, it's about what the viewer wants to see and how they interpret it. The viewer is free to complete the image in their own way, and that desire to create something together is what makes art so powerful. However, I don't like to use the word power in this context. I would replace it with strength. I believe in the strength of words and the connection between people through art. As a visual artist, I also need the support of words to convey my message effectively.

You came to Türkiye for your work during the 90’s and in 2010. For which of your projects did you visit Türkiye and what parts did you go?

My first trip to Türkiye was for my honeymoon in 1972 so Türkiye has always been very special to me. Since then, I have returned for many touristic and work-related purposes. In 1992, the Spanish Consulate organized a beautiful exhibition for me at Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University, which was situated in front of the Bosphorus. During this exhibition, I was given the key to photograph oil wrestling, which was quite complicated to include but fascinating.

I can only photograph things that I love, and I am particularly drawn to the architecture and mysticism of Türkiye. Through my work, I have had wonderful experiences in this country, including working with the Whirling Dervishes, olive oil workers, and even performing gypsy dances in Sulukule. Türkiye and Spain share many things in common, such as olive oils, and culturally, those Sulukule dancers in Türkiye could be Spanish in a very natural way. I have also had the privilege of working with UNICEF in Mount Nemrut. Despite politics, I only focus on people, and Turkish people are very special to me. They are a real heritage. Politics come and go, but the people stay. To understand many things, you must live what many generations have lived.

I understand that those journeys were mostly to take photographs of people and their stories or for a specific occasion but this time, within your upcoming exhibition at Pera Museum, you photographed Göbeklitepe and Karahantepe where there are only human traces but nothing alive. What was the main motivation behind this project and how was the experience from your point of view?

Yes, this time there were no living humans in the photographs, but that was not my focus. I have a passion for archeology and architecture and have previously done work in these areas. When I visited Türkiye, I was struck by the beauty of your cemeteries, particularly the Ottoman cemeteries, which are incredibly poetic. Although the physical figures are not present, the human element is still there. When I see the beautiful Ottoman stones and read the poems on them, I can imagine physically the women they represent. Similarly, when I photographed Göbeklitepe, I tried to immerse myself in the ancient culture and understand it in my own way. I was inspired by the knowledge of stars that they possessed and made use of their understanding of light to create my images. When I photographed Göbeklitepe and Karahantepe, I saw them as living entities. The anthropomorphic animal figures with human figures underneath added to this sense of life. To me, the stones themselves felt alive.

Göbeklitepe is important for several reasons. First, it is one of the oldest known examples of monumental architecture and dates back to around 10,000 BCE, predating Stonehenge and the Great Pyramids by thousands of years. Meanwhile, it also challenged our understanding of how ancient societies were organized. The construction of such a complex structure suggests the existence of a sophisticated social structure and organization at the time.

In addition, the site provides valuable insight into the religious and symbolic beliefs of ancient societies. The numerous T-shaped pillars found on the site, some of which are elaborately decorated with carvings of animals, suggest that the site was used for ritual and religious purposes. Lastly, the site's discovery and ongoing excavation have sparked renewed interest in the study of prehistoric societies and their cultural and technological achievements. It has also highlighted the importance of preserving and protecting archaeological sites for future generations. What were your main reasons for selecting this area?

At first, it was the novelty of the discovery that intrigued me. As a photographer, I have a natural curiosity and a desire to explore new things, and even before I had a camera, I was seeking to understand how people in the past lived and felt. In Spain, we have a rich tradition of Paleolithic art, but in Göbeklitepe, I found a spiritual element that spoke to me. In Spain, we have bullfighting, which is a very controversial topic today. While I love animals and am against these fights, it is still a part of our culture, and we have always been taught that it came from the Minoans. But a year ago, we discovered the first relief of bullfighting, and it changed our understanding of our own identity. Sometimes we can become overly confident and feel that we know everything, but this is a mistake. We are nothing in the grand scheme of things.

Beyond what Göbeklitepe means to me personally, I also consider what it can mean to other people. In Türkiye, I was fortunate to receive permission from Professor Necmi Karul to explore the site. It's not just about touching but being in the presence of these ancient artifacts and seeing the bodies of the sculptures together can evoke many emotions and sensations.

In the contemporary art world, both locally and internationally, Göbeklitepe is a source of inspiration for artists. I remember Taner Ceylan’s series of works inspired by the carvings in Göbeklitepe. His paintings feature highly detailed depictions of animals and other symbols, rendered in a photorealistic style. Another example is Murat Germen’s series of images of the T-shaped pillars at Göbeklitepe. His photographs highlight the intricate carvings and the unique shapes of the pillars, and they often incorporate elements of nature and the surrounding landscape. Also, Julian Charrière who created a video installation inspired by Göbeklitepe. His work, titled Towards No Earthly Pole explores the site's significance as a marker of human history and our relationship with the natural world. Are there any artworks that also shaped your vision before (or after) your visit?

I would love to see their work, but I don't know it yet. I prefer not to see others' work beforehand so that I'm not influenced by it. I always approach my work based on what I feel in the moment. Of course, I have ideas for installations, and I need to prepare my team, but I want my approach to be pure and free from any outside influence. For me, it should be untouched and pure.

Karahantepe, which is located just a few kilometers from Göbeklitepe, is an important archaeological site in its own right. It was first excavated in the 1970s, and it has yielded important artifacts and structures dating back to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, including a large stone wall and a temple complex.

The relationship between Göbeklitepe, Karahantepe and Sayburç is important as it provides evidence of a larger social and cultural network in the region during the Neolithic period. The construction and use of these sites would have required significant social organization and communication, suggesting the presence of a more complex society than was previously thought to have existed in the region at that time. I see that you did not divide these three areas. Why were they inseparable to you?

Thanks to Professor Necmi Karul, who gave me the address, I had the opportunity to visit several archaeological sites in Türkiye. Each place I visited had a different impact on me. While Göbeklitepe was as we had discussed, Karahantepe was inhabited and had remarkable stones in the form of vaginas and temples. Seeing how human beings began constructing round architecture was a unique experience. The significance of the round shape in architecture is quite special. Karahantepe is also interesting archaeologically because they used to construct their houses as a unit of communal living. Whenever something tragic happened, they would cover it up with respect and move on to building another house. This practice interests me because it shows that places hold memories. Sometimes, it's challenging to look at the same objects after a tragedy. Covering them up was their way of preserving those memories. I believe humans are made of feelings. Although Göbeklitepe is monumental, Karahantepe is special to me.

During my visit, I also discovered Sayburç, a very small area. There, I saw a relief of bull fighting that impressed me, especially after seeing all those anthropomorphic figures. I also saw a real human figure holding something in front of a bull. To be honest, I can never get enough of these archaeological sites. I would love to have access to all the areas. I visited Türkiye twice, in September and then in January, and both trips were intense. When I work on something I love, there is no measure, and when I'm allowed to work, there is no time limit.

I know that you first thought of the name “Origin” as the exhibition title at Pera Museum. What does the origin of the world, of life, mean to you?

It has always been a dream of mine to speak about the origins that have influenced my work. What legacy will we leave for future generations? We need to believe that there is something greater than us and this is what drew me to explore this fascinating subject. Origins hold many meanings for me; the beginning of everything, the first domesticated grain, and the need for human communication and the circulation of knowledge, to name a few. Even though I'm not an archaeologist, I believe in human beings and have seen both their dark and bright sides. We needed to hear stories for thousands of years, and our desire to believe in something beyond ourselves has given birth to the concept of eternity.

In the case of Göbeklitepe, it's not just about the origins, but about eternity as well. The site represents the beginning and the end of a civilization, as it came to a point where its creators said "we want to cover it. Our civilization is finished." This mysterious aspect of the site allows us to dream about what happened there, but we cannot be certain. This is why we changed the name of the exhibition to A New Story, which reflects the fact that the discovery of Göbeklitepe has changed scientific knowledge and represents a new story for my work.

Curator François Cheval suggested the name, and the Pera Museum team agreed to it. The exhibition mainly focuses on Göbeklitepe, but there is also a section on Karahantepe and Sayburç. I come from Córdoba, a beautiful Spanish town that was once the capital of the Muslim world for 800 years. The most beautiful mosque in the world, for me, is located there. Unfortunately, when the country was invaded, everything else was destroyed except for this mosque, which was protected by a group of people.

There are new techniques you are using in this exhibition: Tepetype and charcoal print. Have you used these techniques before and what do these novel productions mean to your career or for this series in particular? How do you balance technical excellence with the need to convey emotion and meaning in your photographs?

I am very interested in stepping out of my comfort zone and exploring new things. Currently, I am focused on experimenting with printing techniques, particularly platinum prints. I have a strong belief in the power of objects, and I wanted to print on Turkish soil to capture its magic. To achieve this, I have developed a technique called "Tepetype" which involves layering silk screen engravings, similar to the methods used in ancient times. This results in a mixed media print that combines archival printing methods with a beautiful texture created solely from stone.

We have also experimented with gold and silver prints using 24 karat gold and glass, inspired by the calligraphy of Ottoman culture. Calligraphy is a significant part of their legacy, and I wanted to pay homage to it through these prints. Each piece we have created tells us a story about that time.

While we did not use carbon prints in this project, which is associated with the origin of photography, it still held significance to us due to the use of carbon-14 in archaeological excavations. We have continued to explore other techniques in our pursuit of creating meaningful and unique pieces.

How has the photography industry changed since you first began working, and how have these changes affected your work? How do you think advances in technology, such as digital cameras and social media, have affected the photography industry, and how do you see technology evolving in the future?

I am very enthusiastic about embracing the advancements that technology brings us. It facilitates a lot of creativity and innovation. However, there are concerns about how it will impact the future. I am always investing and researching to keep up with these developments. In the future, the streets we walk on will become a part of our history, even if historians only tell the stories of the winners. There are many stories that will be told by cameras in the coming years. We must prepare the new generation to learn how to use this technology.

As we discover more about AI, there needs to be legislation in place to regulate its use. It has the potential to limit our freedom, and my generation highly values freedom. It is a risky situation if someone has control over our liberty. While I am in favor of technology, I believe there should be checks and balances. There are always risks and benefits to using technology, and this exhibition is an example of how I have used it to explore and understand our past.

In my discussions with archaeologists, I learned that bones and other parts might be missing from discovery. They left us with everything they could, but in addition I wanted to create an auto portrait. The helmets that measure EEG activity are fascinating, and I used them to study my brain. When the helmets were placed on my head, the fireworks of neural activity exploded all over my brain, each connection represented by a different color. I projected my EEG onto one of the heads found at Karahantepe, a mysterious head that some believe to be a snake, while others think it's a man. This piece is my first experience and a representation of my self-portrait, created during an era when people didn't even know how the brain worked.

You have won numerous awards throughout your career such as Fundación DEARTE (2012), UNICEF Spain Awareness Rasing Award (2010), Bartolomé Ros Prize, PHotoEspaña (2009), Spanish Ministry of Culture Gold Medal to Fine Arts in Spain (2009), The first prize in photography by Comunidad de Madrid (2006), The two World Press Photo prizes (2000 and 2004), The Biennial of Alexandria Gold Medal (1999). Which award or recognition are you most proud of, and why?

Back in my school days, periodically they would give out a beautiful bag to the good girls who behaved well. As we grew older, we were given medals. However, I was never able to receive one of those. When I received my first recognition, it made me think of those days. Every time I am recognized for my work, it reminds me of my past and inspires me to continue growing. I feel fortunate to be recognized because it means that someone else may not have received it, and they deserved it as much as I did. This recognition gives me the strength to move forward and continue my path. The most recent recognition I received was special to me because I became the first female photographer to be a part of the Royal Academy of Beaux Arts. Photography has given me so much, and I want to give back even in the smallest way possible. Art historian Publio López Mondéjar has done a lot to position photography, and even though it's not always easy, I still have hope. The association is happy to push photography, and I am grateful for that.

What legacy do you hope to leave with your work, and what impact do you hope it will have on future generations? What projects are you currently working on, and what can we expect to see from you in the future?

At the moment my concern is for future generations. My goal is to use my work to create as much positive change as possible and to better their lives. I'm not worried about what will happen to my work after I pass away, as I believe we cannot bring anything with us. To be honest, it will be good to preserve my work when I'm no longer physically here to serve future generations. I'm not possessive and want my work to serve the people. I'm currently working on a project with blind people, and I need to have projects to continue with life. Unlike some, I don't worry about my work, but rather wish for it to be shared. I believe art should be given to museums to be shown and not accumulated in boxes. It's important to have documentation that's freely accessible from anywhere in the world. However, it's not the same to study a digital image as it is to see the real thing. In a digitalized world, humans may start to have mental problems because we need to touch and feel things. We cannot solely rely on digital experiences. For example, it's not the same to see a replica of a paleolithic cave in a museum as it is to see the real thing, to feel it, and smell it.

Photographs: © Toni Català

Inspired by the exhibition And Now the Good News, which focusing on the relationship between mass media and art, we prepared horoscope readings based on the chapters of the exhibition. Using the popular astrological language inspired by the effects of the movements of celestial bodies on people, these readings with references to the works in the exhibition make fictional future predictions inspired by the horoscope columns that we read in the newspapers with the desire to receive good news about our day.

Pera Museum, in collaboration with Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV), is one of the main venues for this year’s 15th Istanbul Biennial from 16 September to 12 November 2017. Through the biennial, we will be sharing detailed information about the artists and the artworks.

Martín Zapater y Clavería, born in Zaragoza on November 12th 1747, came from a family of modest merchants and was taken in to live with a well-to-do aunt, Juana Faguás, and her daughter, Joaquina de Alduy. He studied with Goya in the Escuelas Pías school in Zaragoza from 1752 to 1757 and a friendship arose between them which was to last until the death of Zapater in 1803.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)