12 November 2019

Pera Museum presented a talk on Nicola Lorini’s video installation For All the Time, for All the Sad Stones, inspired by the Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection, bringing together the artists Nicola Lorini, Gülşah Mursaloğlu and Ambiguous Standards Institute (Avşar Gürpınar, Cansu Cürgen) to focus on concepts like measuring, calculation, standardisation, time and change. Enjoy the short text that is compiled from the inspiring talk!

Ambiguous Standards Institute

The cryptic, fluid and fragmented structure of everyday life require specific ambiguous descriptions, instructions and standards. Definitions of ambiguous standards are made using ingredients, spatial data, anatomic references, thus ‘loaded’ categories. Given standards enounce proximity, not certainty related to the dimensions of the notions they signify. Most of them are qualitative instead of quantitative, thus challenging to investigate solely through physico-mathematical methods and analysis.

The Ambiguous Standards Institute is a design-debate initiative based in Istanbul, dealing with the secondary impulses of the standards on our design environments. Ambiguous standards are the words that describe, represent mostly physical equivalences or analogies between the appearances, and the amounts of the goods, primarily function-based on the four principles of representation defined by Aristotle and later by philosophers. These principles are analogy, identity, similarity or opposition. So, we are using these principles to understand design environments as part of our standardised worlds, but in between these relations, ambiguities emerge.

On the other hand, we have seen that a long part of human history has passed without these central institutions of standardisation. We recognize that, especially towards the end of the 19th century, individual national or international institutions began to be established to ease up the commerce process or come up with a specific grading, normalization and standardization system, so that the flow of goods, money and people, and all kind of objects becomes much easier.

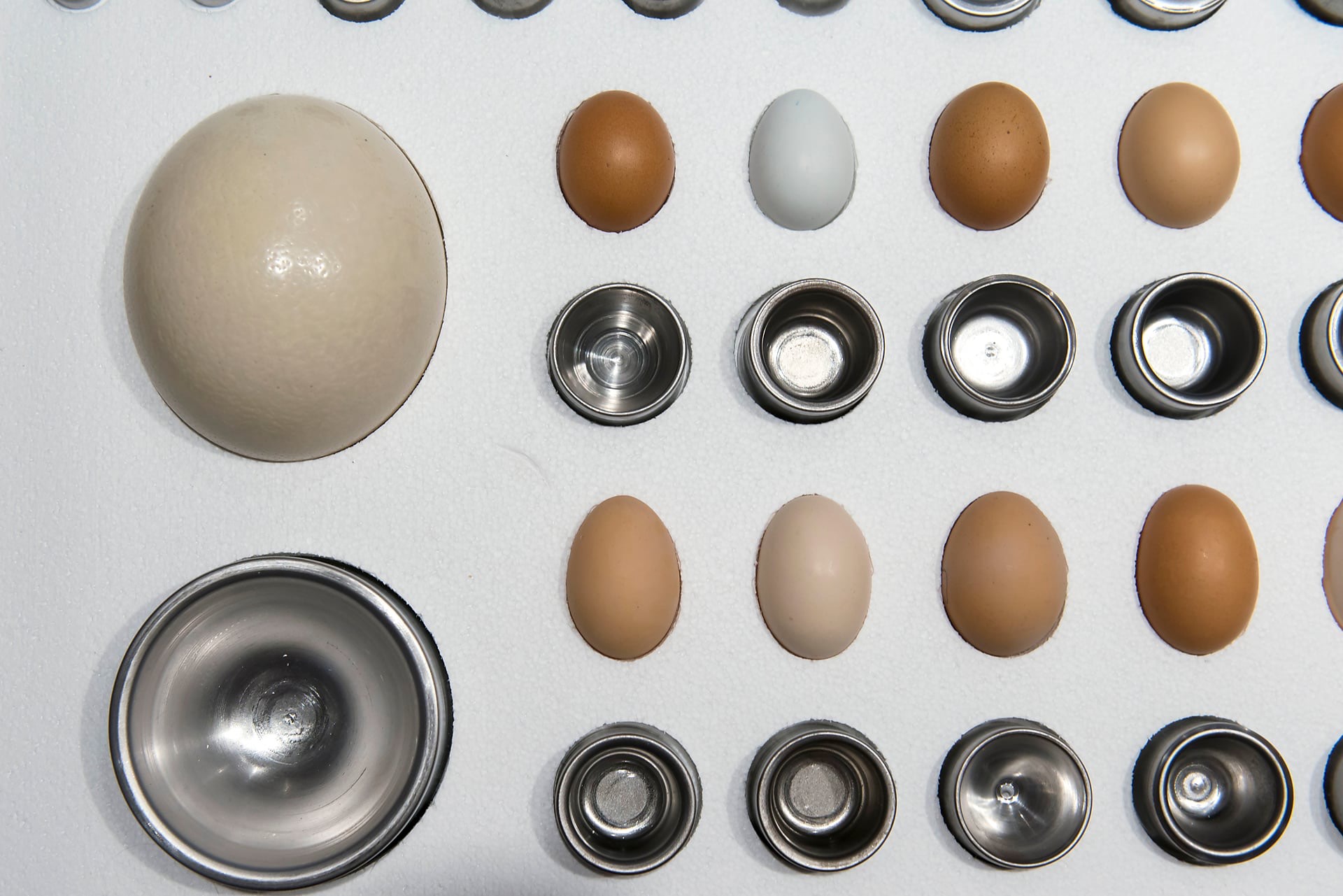

How these standards and the objects in the world relate to each other, how standards are not only standards, can be visualized through an elementary example: The journey of an egg from the rear of a chicken to our tables. It gets out of the back of the chicken; it goes into a viol (box). This object should have a particular shape to accommodate the egg. The viol goes into another carton box, that box goes into another box, and multiple boxes come on to a palette. They all go into a container which also has a particular standard, which goes into a big ship, and then again, going smaller and smaller, it goes into the supermarket, then into the refrigerator and then onto our tables and the egg holders. When we talk about a standard, we are not just talking about the standard itself, but this infrastructure, the whole network of relations tying them together.

First, we should see how we came up with the idea of a kilogram. So, the first idea was to take something from nature and equalise it to 1 kilogram, so that everyone can use the same thing. A piece of ice…. 0.1 m3 of water equals to 1 kg. But then, we realised that the weight of water changes a lot. So, we came up with a new idea. In the late 19th century, we equalled it to a piece of mass, another weight. For a century, it stays like that. So, the weight of everything is related to the weight of another object. The original kilogram rests under three layers of vacuumed environment. Even these cautions are not sufficient for the mass to resist the natural changes, so it loses weight. So, in the 21st century, in 2019, we decide to change that as well because that weight, our standard weight, is losing weight. Only about the weight of an eyelash, but still. So, we equalise, tie it to the Planck constant. We can calculate or be sure about its one kilogramness to a very microscopic degree, so to say.

There’s something very modern and non-modern about this. On the one hand, it’s quite modern as it tries to reason nature by setting a standard and organising everything around that rule. There is also something non-modern about this because it does not make sense, it’s illogical, or it resonates the same thing humans did centuries ago: The weight standard before this, in prominent modern eras, was also fixed to a natural object. It was the weight of a particular core of a vegetable. Thus, it’s practically the same thing, like equaling 1 kg to 1 L of water.

The whole world is in some frenzy to deal with the ambiguity of the world. So, this is maybe the reason why we have all sorts of standards, fixations on the size and the measures, and everything because the other side, the taste of something, you cannot standardize it as everything is so both ambiguous and relative. It is also a psychological obsession that we don’t want things to be undefined. We want everything to be categorised and fixed. Not knowing something, not being able even to name something create restlessness. Thus, we collectively work towards this definition and identification of things.

Eventually in design, commerce or art, even environmentalism, we see an overemphasis on the importance of human beings. Maybe, this is why our having new types of philosophies which give equal importance to humans and non-humans, animate and inanimate things, or calling everything objects, proper objects. So, maybe it’s time to see what the planet has come to, environmentally and geologically. Perhaps it’s time to realise that although we are essential, we give value to ourselves, we have self-value, we are also not more important or valuable than any other thing around us.

The 10.000 objects of the Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection from a period covering 4.000 years of history resonated in my mind for a while, until the point I decided to come to Istanbul to visit the collection. I was expecting massive buildings containing all these objects, surprisingly the archive was quite small, most of the items have the size of a coin. The research I developed after the first visit happened at a distance and I dealt with the collection like if I was working with a landscape without being in it. This allowed quite a lot of speculation.

Since the beginning I was driven by a fascination for the fact that these objects gathered together became a sort of “photograph” of human efforts and struggle to define things, to make sense of what is “out there”. I didn’t want to focus on a specific aspect or artefact in the collection but rather engage holistically with that dense accumulation of characters, moods, figures, materials, and surfaces. I was interested in accessing the archive emotionally.

I started collecting images and stories, Iayering references horizontally. At the beginning I was interested in the punishments given to people who were not respecting measures.

Within this process I came across two stories that later on became the background of my project. One was the redefinition of the kilogram model, a platinum-iridium cylinder conserved in Paris that in 130 years lost weight. The other one was a web news about the attempt to define the physical weight of all the electrons making the Internet possible in this exact moment, which apparently is the weight of a medium size egg. On one side the preoccupation for the disappearance of a physical model, on the other side the necessity of making material an “immaterial” aspect of the Internet.

I think we find ourselves in a moment of human experience that, due to the impact of digital paradigms and, even more, due to the climate crisis we are facing, is facilitating a reconsideration of specific models of thought typical of western culture. In a context, in which questioning an anthropocentric understanding of things became a necessity, a set of inevitable questions arises. This doesn’t involve only the relationship human/nature, natural/artificial but it expands to dualistic understanding of good/bad, past/future and in so the notions of history and time, meant as purely linear phenomena, start collapsing.

The development of the installation For All the Time, For All the Sad Stones took place with these questions in mind.

Gülşah Mursaloğlu

When I met Nicola last week, to see the piece he installed in the Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection, we started talking about the two recent phenomena that inspired his installation: the change of the kilogram model and the calculation of the weight of the internet. Then I went home, and started researching how the kilogram model changed from a material to an immaterial state and what I found most interesting was the intense and extreme measures that were taken to protect this object; the big K, and how precious it was.

As you can see in the image above, the big K is placed in three different bell jars, on top of one another, which in turn are each sealed. These bell jars have been then placed in two separate safes and stored in a controlled environment, in a basement in France since 1879 — so ever since the big K was set as the standard. There are three separate keys to open these vault cells; two of which are stored in France, and one that is located elsewhere. Over the years, the big K was only removed from all of these vessels every 40 years to be taken and compared to the other standards around the world. The procedure of removing it is also very specific and ceremonious; no hands or gloves are involved. They remove it with a specific tool that is right next to it in the picture, and this tool is covered with filtered paper. So, in other words, all possible measures are taken to prevent this object’s interaction with other elements in the world. I find the efforts we devote to controlling and manipulating a certain matter by isolating it quiet fascinating.

As you can see in the image above, the big K is placed in three different bell jars, on top of one another, which in turn are each sealed. These bell jars have been then placed in two separate safes and stored in a controlled environment, in a basement in France since 1879 — so ever since the big K was set as the standard. There are three separate keys to open these vault cells; two of which are stored in France, and one that is located elsewhere. Over the years, the big K was only removed from all of these vessels every 40 years to be taken and compared to the other standards around the world. The procedure of removing it is also very specific and ceremonious; no hands or gloves are involved. They remove it with a specific tool that is right next to it in the picture, and this tool is covered with filtered paper. So, in other words, all possible measures are taken to prevent this object’s interaction with other elements in the world. I find the efforts we devote to controlling and manipulating a certain matter by isolating it quiet fascinating.

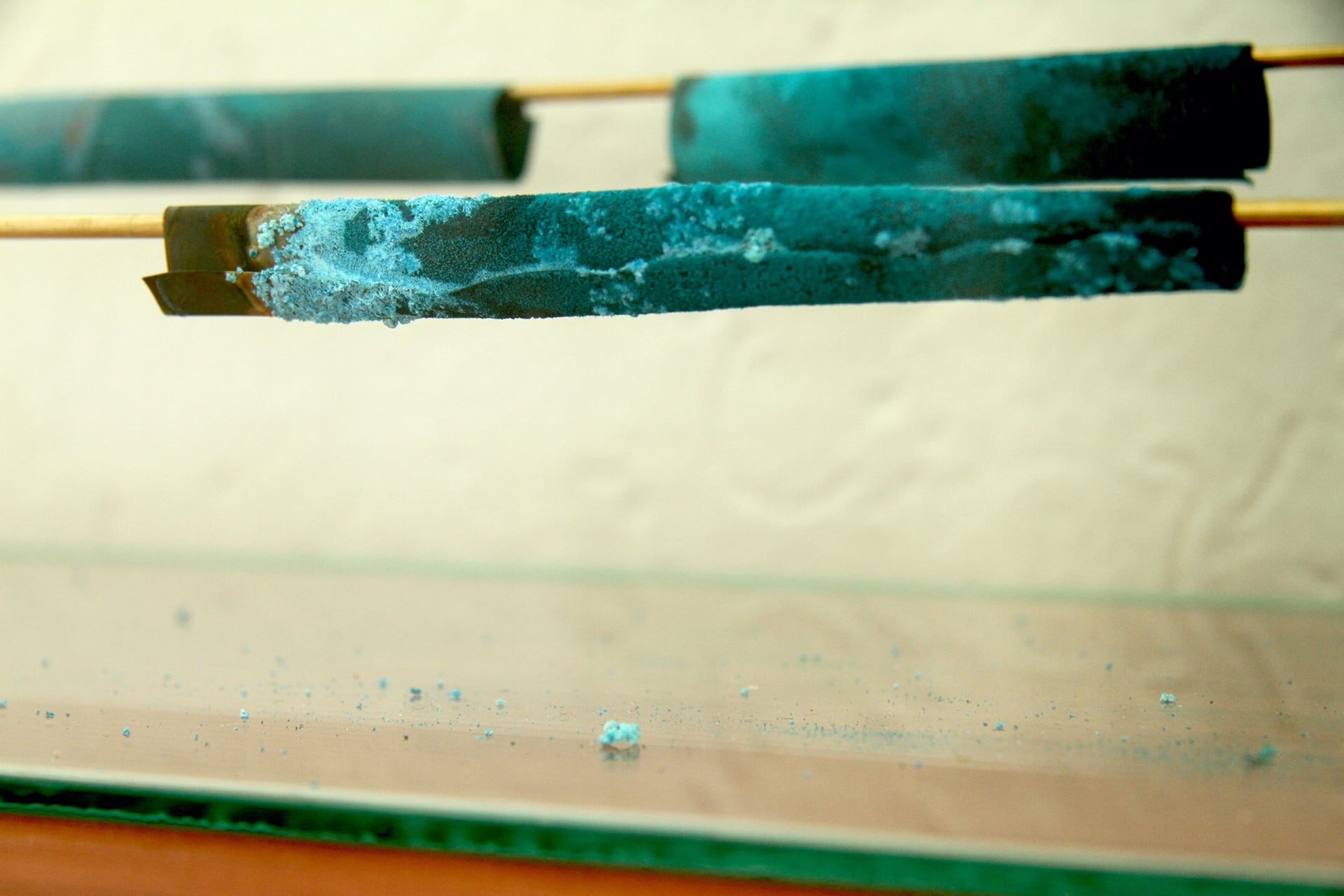

The big K is made from a platinum and iridium alloy. Both of these metals are really dense and malleable, highly radioactive and have high corrosion resistance. So, even in 2000˚C, iridium doesn’t show any sign of corrosion. In that sense while designing the big K, scientists picked the two metals that would collaborate with them the most, which I found interesting. Ever since I started having a studio practice, I’ve been interested in this urge we have, as a species, to control matter, to shape and manipulate it in ways, which serve our purposes.

I’m also interested in the hierarchies we create between us and other species and the matter that surrounds us. We often position ourselves as superior to the matter that we define as inanimate, and ignore the fact that matter is also shaping us in various ways. The results of this approach are becoming more alarming than ever with the effects of climate change being more visible. A new approach that recognizes this continuity between us and the matter proves to be essential. When I’m working in the studio, I try to avoid these hierarchies as much as I can, consider materials’ respective agencies and conceptualize the work as a collaboration between myself and the materials. So, whenever I do an intervention to a material or facilitate an encounter between them, I try to wait and observe their reactions and choreograph the rest of the work accordingly. Of course, these observations and reactions happen within various temporalities, and some of these intervals will definitely outlive me, and I’m interested in these non-human temporalities that are larger and smaller than ours.

So the big K, losing weight despite all of these human measures was for me a fascinating manifestation of the fact that no matter how much we try to designate ourselves as the main agent behind all earthly operations, matter finds ways to exert its own agency and show its presence.

Inspired by its Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection, Pera Museum presents a contemporary video installation titled For All the Time, for All the Sad Stones at the gallery that hosts the Collection. The installation by the artist Nicola Lorini takes its starting point from recent events, in particular the calculation of the hypothetical mass of the Internet and the weight lost by the model of the kilogram and its consequent redefinition, and traces a non-linear voyage through the Collection.

In 1962 Philip Corner, one of the most prominent members of the Fluxus movement, caused a great commotion in serious music circles when during a performance entitled Piano Activities he climbed up onto a grand piano and began to kick it while other members of the group attacked it with saws, hammers and all kinds of other implements.

Mersad Berber (1940-2012), is one of the greatest and the most significant representatives of Bosnian-Herzegovinian and Yugoslav art in the second half of the 20th century. His vast body of expressive and unique works triggered the local art scene’s recognition into Europe as well as the international stage.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)