24 April 2012

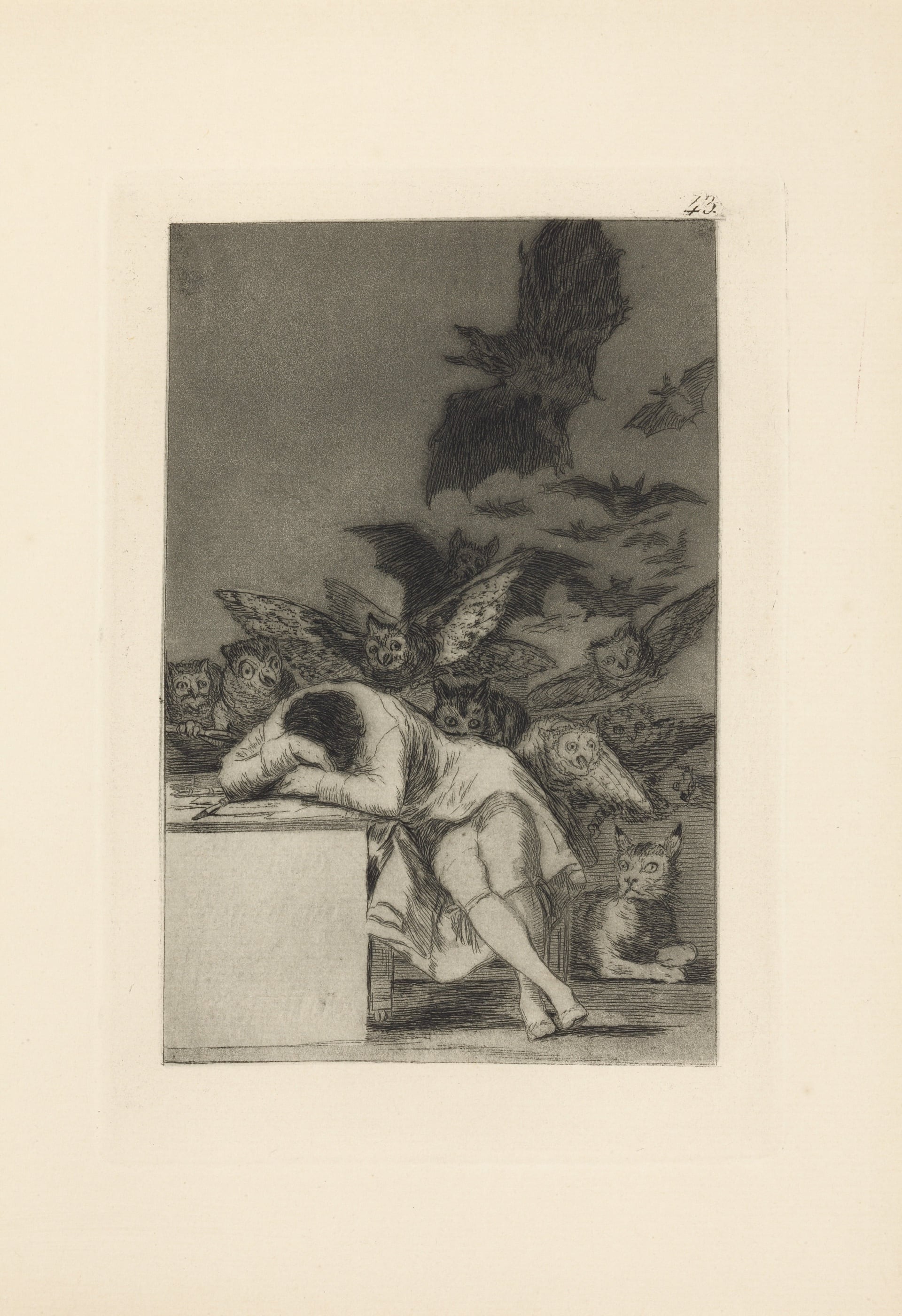

It can be seen how Goya gradually and constantly investigated all the technical possibilities of creative engraving from etching to lithography. His first series was a collection of copies of paintings by Velázquez in 1778 and also his first failure as an engraver; however, this work would contain the seeds of his subsequent graphic creations, starting with Los Caprichos.

In the Spanish Dictionary of 1729, capricho (caprice) was defined as “a judgement formed by an idea [of intent] and in general outside ordinary common rules. It seems to originate as a compound word derived from Caput and Hecho (fact), like made in one’s own head [a creation]; but it is doubtlessly taken from the Italian Capricio. In painting, it is synonymous with concept”. Goya, according to this, was a capricious man, i.e. one who “has the sharpness to form singular ideas, and with the novelty that they will be successful”. Today’s Spanish Dictionary indicates that capricho is a “determination taken arbitrarily, inspired by a whim, humor or delight in the extravagant and original”; and also a “work of art in which ingenuity or fantasy break the observance of rules”.

This collection comprises eighty prints dealing with whimsical subjects, created and etched by Goya, put on sale in 1799. The intention of the master from Fuendetodos was explicit and no one better than himself (possibly with the aid of the writer Leandro Fernández de Moratín) has explained it:

“The artist was convinced that censorship of human errors and vices (even though this may seem peculiar to eloquence and poetry) can also be the object of painting, and has chosen as subjects for his work, from the multitude of extravagances and mistakes that are common in any civil society, the concerns and common lies, authorized by custom, ignorance or interest, those that he believes most apt to supply material for ridicule, and at the same time exercise the artist’s fantasy. This creator has neither followed the examples of others, nor has he copied from nature”.

Goya began his sketches for the engravings in two albums created in the residence of the dukes of Alba, in Sanlúcar de Barrameda (Huelva) and in the so-called Madrid Album. The strong critical-satirical tone of the prints irritated the Inquisition and Goya offered the eighty original copper plates and the unsold collections to King Charles IV. The monarch accepted the offer (1803) and in exchange took the painter’s son, Javier, into the service of the Royal House. Goya stated that ignorance and passions are the objects of his criticism.

The Caprichos were well known outside Spain. They were the first symbol of “Goyesco” or Goya-style and a new way to depict reality, presenting it as close and expressive, with a fresh and daring language, which was to influence 19th century artists. His work put an end to cold and artificial neoclassical engraving.

An extract from the article by Ricardo Centellas Salamero, Member of the Real Academia de Nobles y Bellas Artes de San Luis de Zaragoza, from the exhibition catalogue.

Martín Zapater y Clavería, born in Zaragoza on November 12th 1747, came from a family of modest merchants and was taken in to live with a well-to-do aunt, Juana Faguás, and her daughter, Joaquina de Alduy. He studied with Goya in the Escuelas Pías school in Zaragoza from 1752 to 1757 and a friendship arose between them which was to last until the death of Zapater in 1803.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)