12 August 2016

Pera Museum Blog is publishing the last one of a series of creepy stories in collaboration with Turkey’s Fantasy and Science Fiction Arts Association (FABISAD). The Association’s member writers are presenting newly commissioned short horror stories inspired by the artworks of Mario Prassinos as part of the Museum’s In Pursuit of an Artist: Istanbul-Paris-Istanbul exhibition. The fourth story is by Galip Dursun! The stories will be published online throughout the exhibition. Stay tuned!

The voice recording, whose transcript appears below, was made at the crime scene of the terrorist attack on the 5.45 p.m. Eminönü-Kadıköy ferry on May 26, 2016, consisting of a recording found on a cell phone taken into police custody and registered as A0530/2016/009361; the recording was translated from the Arabic by C… Y…

The contents have been listed under headings designated according to file names.

2016-05-26_16_33.m4a:

I remembered a game as I was waiting in the passenger lounge for the ferry to arrive just a few minutes ago. A game we used to play at home when I was young, in my country that is very far away from here, a relic from the distant past; I don’t even remember how we used to play it. The kind of game that makes me feel a thousand times lonelier than I already am among the crowd waiting to get on the ferry.

Was it like the game I played as I sneaked on the ferry like a ghost, holding a box under my arm? I don’t remember.

My mother used to say that all games were alike. Her voice echoes in my mind but comes from so deep down I can barely hear it. I still recall the time she put me on the bus to Istanbul at the Burdur bus terminal. She says she’ll buy a pack of cigarettes and be right back, and smiles. “I’ll come with you,” I insist, but to no avail. She leaves. That’s the last time I saw her. I forgot about her until the day Rıza Bey brought us back together. That’s a shameful thing.

Rıza Bey says “Remembrance is the curse of the mind.” He taught me a whole bunch of things, but I guess this is the most important one.

Rıza Bey… Well…

That’s not how I intended to begin. There’s an order to the things I want to tell; I wrote them down on paper. The cardboard box sits in my lap, making my legs sweat. I couldn’t resist saying it. Excitement makes me babble. The dude sitting across from me gives me a look.

2016-05-26_16_34.m4a:

I got rid of him. Now I’m sitting all by myself in the last row in the back. I’m recording this in Arabic so no one knows what I’m saying. Still, some people stare at me. They don’t like me, us. And I don’t like them. But I’m digressing; I don’t have much time.

We’ve just departed. The ferry will go from Sirkeci to Kadıköy. And I, Elif, will tell you everything that happened, in the order it happened.

I was born in the Syrian city of H… I was the oldest of five siblings. It seems like ages have passed since my childhood. I’ve forgotten even what the place we used to live looked like. But it was a small, likeable place. It didn’t look like Istanbul or the other cities we took refuge in. Dad had a domestic appliances store. He had met Mother in college. But because I was born a bit early and through illegal means, both had to drop out. The last time I saw Dad was three years ago. I don’t have a clue about how the war broke. The insurgents didn’t like us, and neither did the soldiers. So our only hope was to run away. In order to get us through the border to Turkey, my father… sacrificed himself.

I can’t… go on…

2016-05-26_16_35.m4a:

I have to go on. I’m 19. I lost my family at the border crossing, and we found each other through sheer luck a few months later at the immigrant camp. The things we went through as Mother and my siblings and I went from town to town to stay alive… Now, thinking back, it feels like they all happened to someone else. Rıza Bey used to talk about that. He said the human mind tried to protect itself.

As we were whipped from one place to another, we received news of Dad. Some people we knew were talking about a man who said he had seen my father. We had to decide whether to move on to Europe or stay in Turkey and wait for him. We had to find him. Mother went to talk with these men. She looked very upset when she came back. But she tried not to show it. She forced herself to smile as she gave us the good news. Dad was in Istanbul.

Mother and I decided to leave my siblings with our relatives, who were better off than us, and go to Istanbul. She had found out that her people lived in Burdur; we would go there first and ask then to lend us some money. Then we would go to Istanbul to meet Dad. Mother was always going off to places, meeting with people who brought news of Dad. Every time she came back looking more worn out and hopeless. The Burdur Bus Terminal… That’s where I last saw her…

I came to Istanbul two years ago, on my own.

2016-05-26_16_36.m4a:

The ferry approaches the Maiden’s Tower. Even though I’ve seen it dozens of times in two years, its beauty still fascinates me every time. I probably got this love for the Maiden’s Tower from Dad.

Once, before he got married to Mother, Dad had come to Istanbul on business. And he was smitten. Whenever he talked about Istanbul he turned into another man, jumping to his feet and taking me or one of my siblings by the arm and giving us a fast-paced tour of Istanbul in the living room of our house. Mother would get secretly jealous and make innuendos, but he wouldn’t mind, and keep talking about good things. In my father’s Istanbul, there was no room for evil. Like all the man who carry more than one love in their hearts, Dad had many favorites. But his greatest love was the Maiden’s Tower.

Incidentally, that’s how I got my name. The elegant figure of the tower rising in the middle of the sea inspired my name, Elif, incongruous really with a baby like me, tiny and weak. Loving the Maiden’s Tower is like my father’s legacy to me. And whenever I see it, I forget all my troubles and woes, and drift away.

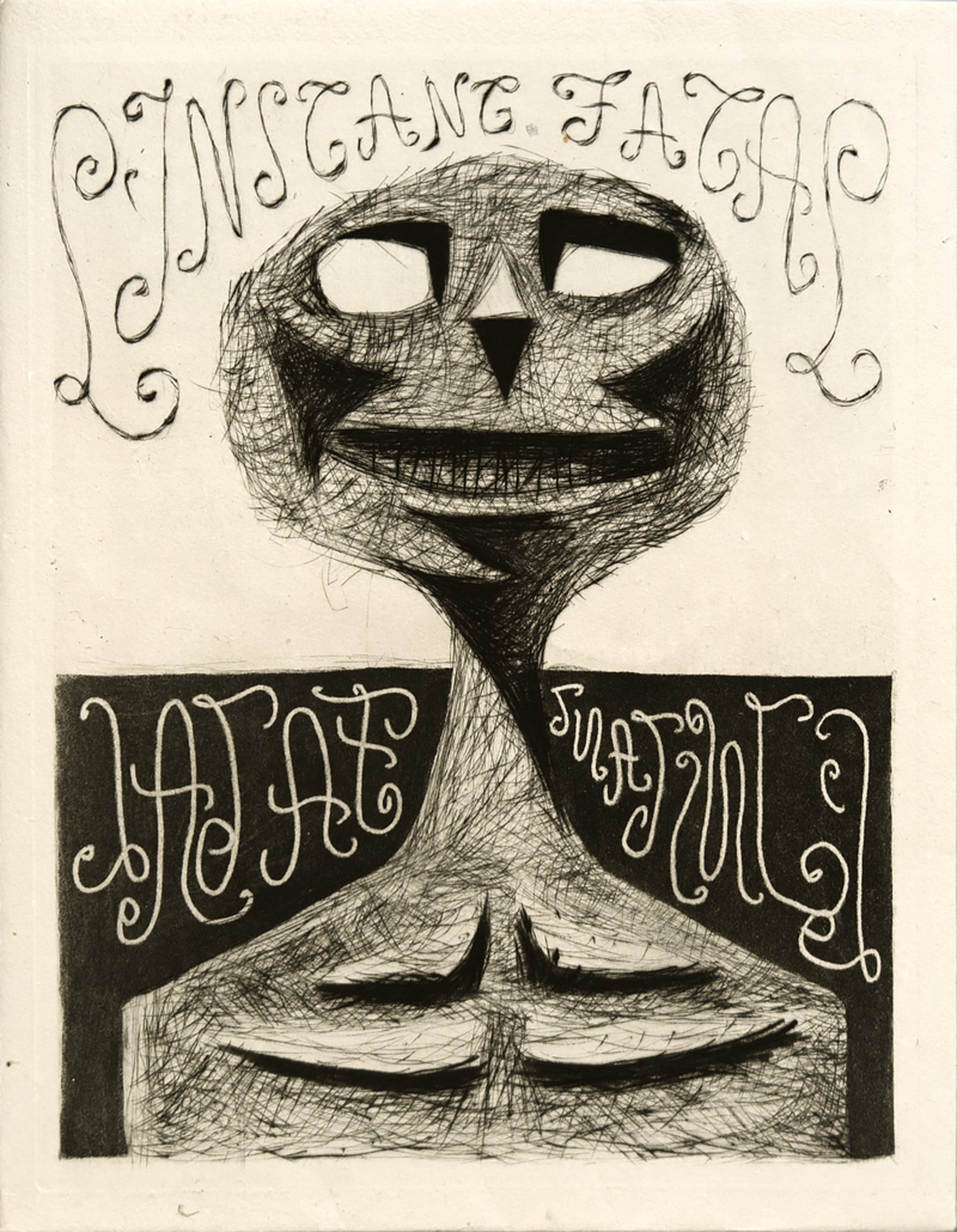

Ochre-Black-Yellow Autumn, 1962, Aquatint, etching and engraving on copper,

76,2 x 57 cm., FNAC 35358, Centre National des Arts Plastiques

Rıza Bey would point at the Bosphorus and the deep water that separates Asia and Europe, and say, “The Bosphorus is where good and evil meet. These waters mix the good deeds and the evil deeds of the two continents. They become one; they become Istanbul.”

There is one thing that Rıza Bey fails to mention, without which all this grand talk is really shallow. The Maiden’s Tower is where these two worlds meet. Maybe it’s not located right in the center, maybe the division has not been made justly, but it does separate everything from each other. Just like I do.

2016-05-26_16_37.m4a:

I have to speed up. Let me quickly cover the part after my arrival in Istanbul. Not much left to Kadıköy.

I was on my own when I got here. I was unable to reach my siblings or my mother. I didn’t know what to do, I couldn’t speak the language, I didn’t know my way around the city, I had no job… I slept on the street. I begged for money; I did what I had to do to survive. I even worked for a short while. But there, too, I was…

I’ve written many things on this paper I hold in my hand. But I don’t want to talk about any of them. All I want to say is this: the Istanbul I saw had nothing to do with the fairy land Dad had fallen in love with.

I tried to stay alive for a year, doing everything you can imagine. Then I made my peace with all that had happened to me. The day I thought of killing myself, which was maybe the thing I should have done on the first day, I met Rıza Bey.

2016-05-26_16_38.m4a:

I look at my fellow passengers on the upper deck of the ferry instead of watching the view outside. I’m not interested in the view. Hiding behind my glasses, I watch the people around me, which surprises me every time. People are so strange. They look like they are wearing disposable masks. None of them makes an impression on you.

On the other hand, it’s impossible to forget Rıza Bey’s face once you’ve seen it. It’s like a kite – a tetragon standing on one of its corners.

Seriously.

When I told this to Rıza Bey, he laughed and laughed. I met him at restaurant where I was about to order my last lunch at a nice restaurant with my last money. Actually… that’s a lie.

It wasn’t my last money. And we weren’t at a restaurant. We were at a small pub, and I had been taken there by a man who kept telling me how beautiful I was. We weren’t having lunch. I was gulping down whatever I laid my hands on.

I don’t remember the face of the man who took me there. But I have a good excuse for that. His breath smelled horrible, and I looked away from his face as much as possible. The man thought I was being coy, which aroused him even more and he continued his compliments, dribbling. It was while I was looking away that I met the smiling eyes and the tetragonal face of Rıza Bey sitting at the end of the long table where we also sat. We eyed each other for a while under the dim light. He nodded towards me and took a sip from his shapely glass. Everything got engraved in my memory – his shortness, his thin neck straining with pleasure, his pointed head. There was an indiscernible meaning in his eyes, and I couldn’t figure out whether it was good or bad.

When the scumbag next to me got up to go to the toilet, Rıza Bey came up to me and whispered in my ear. His voice was unlike any I had heard. It had a calm tone that was definitely not soothing. His words found a way to flow into my brain like clear, pellucid water; I understood everything he said right there and then. I agreed to it. Rıza Bey had gone back to his table by the time the scumbag returned. I told him I wanted to go someplace quitter. His eyes lit up, and without thinking for even a second, he called the waiter and payed the check, and we walked out.

Rıza Bey followed us to a shabby hotel. I knew the kind of place. My mind told me to run away, that something bad was about to happen to me, but I was like under a spell. As we entered the room the man payed cash to rent, I was thinking about Rıza Bey’s words. I said I wanted to take a shower; the man had already begun to undress. I remember turning back to walk to the small bathroom tucked away at the entrance of the small room and opening the entrance door, and then taking a long shower. When I came out, I saw Rıza Bey sitting on a chair smack in the middle of the room. The right side of his face was washed with blood, and he called me over with a mischievous smile.

I was a bit shy, but had no fear as I went over to him. Over Rıza Bey’s shoulder, I looked at the scumbag killed like a pig, lying on the bed. When I saw the corpse whose name I didn’t even know, something inside of me broke, and I felt something was freed. All the things I had been bottling up inside were changing color and shape, slowly filling me up.

When I refocused, I saw Rıza Bey working on his victim like an expert butcher. I saw pieces of flesh placed meticulously on different parts of the bed. The dark pieced all looked the same to me, but Rıza Bey explained them to me at length. For a second, I thought he was talking to himself. But when he nudged me with his stubby finger, I realized he wasn’t. This was my first lesson.

“The man may be horrible, but you’ll see, his meat will be delicious. It’s a common mistake, but don’t be fooled. Bad guys always taste better.” He took the shivering piece of flesh on his finger to his mouth with great appetite and swallowed it. “My dear, try not to waste any part of it.”

I don’t know how I kept down the piece of flesh he offered me. I remember filling with joy as I hungrily licked his crooked fingers. I looked at Rıza Bey with surprise, and the first thing to come out of my mouth was laughter. Which was followed by specialties of the pub kitchen. I barfed on the corpse as Rıza Bey watched me disapprovingly.

We worked on our victim till the break of day. Rıza Bey’s appetite was a sight, and he singlehandedly gobbled up most of the poor guy. When he left me in the room to get a few things, I was exhausted. I knew they would find me right away if I left the corpse there, so I stayed in the room the whole day. In the afternoon, deciding I had nothing better to do, I cleaned the place up. I wanted to kill Rıza Bey by the time he came back when night was falling.

Rıza Bey looked different during daytime. The smiling, nice face of last night gone, replaced by a strange semblance of a man with a long nose that looked like a bird’s beak. He was carrying two big suitcases. We quickly divided up the remains of our victim and made roughly one-kg bags. Rıza Bey had brought me clean clothes, makeup stuff, and a wig of a color different from my own hair. I dressed up; while making up my face, I wondered to myself what I would have done if it hadn’t been for Rıza Bey’s help.

The room was spick and span when we left it room after dark. I thought we would drop off the suitcases in a garbage container and get lost, but Rıza Bey’s question brought me back to my senses. He was asking me whether I knew the people sleeping on the streets, having run away from the war like I did. I suspiciously asked him why he was curious about the others, and his laughter echoed in the street.

Rıza Bey’s smiling face that resembled a kite had come back with the night. He pointed to the suitcases.

“My dear, what will we do with all this meat? We’re not going to throw it away, that’s for sure.”

That night, we went around Istanbul and handed out meat to everyone until both suitcases were empty.

2016-05-26_16_39.m4a:

I can see Haydarpaşa. The ferry stopped to let a cargo ship pass. There’s someone sitting over there, looking impatiently at the Selimiye Barracks. Anyway, I have to continue.

After that first day, I didn’t see Rıza Bey for almost a month. I’m not sure if I was more afraid of seeing him again or of going back to the pub as the last person the guy we had killed was seen with. But I made a point of avoiding the area as well as Rıza Bey. One night, as I was trying to sleep in a park, cold and hungy, someone came up to me. It was him. It didn’t take him long to convince me with a fistful of money and a bagful of meat. I gave the meat to the others in the park and followed Rıza Bey. He was walking fast, and talked like he was in a hurry, although he did pause a few times.

“My dear, I will teach you everything. I know you have it in you, in your bones. I will train you so that everyone will see and adore you.”

We didn’t do it all the time. We didn’t bring in everyone. We took breaks, which Rıza Bey carefully picked and insistently reminded me we needed to allow ourselves to miss the thing we did; during these breaks, he would point at the people we passed and speak like telling me a rigmarole:

“How to choose, where to butcher, how to watch, where to hide – I will tell you all. How to clean, which parts to save, how to smile to their faces, how to cut the meat; I will teach you all.”

Killing wasn’t the only thing I learned from Rıza Bey; I was slowly gaining his insatiable appetite as well. With each passing day, I looked at people, smiled at them, killed them, and ate them more like he would. I changed when I was with him; I became a different person. I tended to forget everything else.

We did great things in Istanbul for about a year.

2016-05-26_16_40.m4a:

At first, I was under the impression that we killed only the bad guys or those who had it coming. But then the line between good and bad disappeared. Some people just gave themselves up to us. Those were the ones Rıza Bey respected the most. People who sacrificed themselves to a higher cause… People offering themselves to the hungry. The good and the bad intertwined as one – like Istanbul.

Some people believed they could go on living with the money they received in return for giving one of their kidneys or a part of their liver. The precious organs they donated… did nothing to satisfy our hunger. But Rıza Bey never turned these sacrifices down, though I knew the real reason why. The only truth for both of us was meat.

Lozenge Figure, 1937, Oil on panel, 39 x 30 cm., Private Collection

One night Rıza Bey introduce me to Mother. She had come to Istanbul with my siblings; they needed money to go to Europe. She thought maybe if she gave one of her kidneys to Rıza Bey we could give her the money for the trip. Mother looked me in the eye and pleaded. I wasn’t even listening to what she said. I couldn’t believe she hadn’t recognized me. I offered her money – I told my own mother to take the money and fuck off. Rıza Bey, on the other hand, had put on his kite face and was watching us with a smile. Mother chose him instead of me, and Rıza Bey accepted her despite my protests.

I ran away. I did nothing to save Mother. I couldn’t. I wanted to find my siblings and take them with me. When I did find them, Rıza Bey was there, too. Along with the other refugees hiding in the building, they had swarmed that small man, busy trying to land the meat packs he was handing out. Something stirred inside of me when I saw those packs. That was my longing for Mother. It was a different kind of love, a new connection between us. It was hunger.

That’s when I realized Mother was dead.

2016-05-26_16_41.m4a:

When I went back a year later to the pub where I had first met Rıza Bey, I couldn’t recognize the place. It was like a century had passed. I found the table where my first victim made passes at me, and sat down. When I looked at the… at the end of the table… I … him again. … had found…

Rıza Bey…

He was actually…

[recording incomprehensible due to noise]

2016-05-26_16_42.m4a:

Here we are in Kadıköy. People are getting up. They want to get off and go as soon as possible. But I have nowhere to go. I’m at the end of my road. I will never get off this ferry.

I have been thinking about the people around me since I got on the ferry; I’ve been trying to sense their smell, guess what the precious meat they hide under their clothes would taste like. It’s a habit I’ve picked up during the last year or so, and it’s a real drag.

Looking at the paper, I see I haven’t left out much. I think I’ve said everything there is to say, apart for this box.

There is a Lupara inside the box in my lap; it’s a hunting rifle, a double-barre with the butt and the point cut. It means “for the wolf” in Italian. According to Rıza Bey, the shepherds in the mountain villages of Sicily use these rifles to shoot wolves.

Lupara isn’t for wolves who enjoy easy flesh or recognize the shepherd’s weak heart from the way he smells. Those are easily staved off by dogs. Lupara is for wild-eyes wolves. The shepherd use the rifle to shoot the wolves who desperately attack the herd. These wolves are desperate enough to enter the Lupara’s range, that’s how much they crave for flesh.

I feel like a desperate wolf hiding in the ferry’s crowd.

Mine was made very cheaply by an old gun repairer in Küçükpazar. It was a bit difficult finding the right cartridges, but I took care of it. You would be amazed how easily you solve your problems once you have decided to commit suicide.

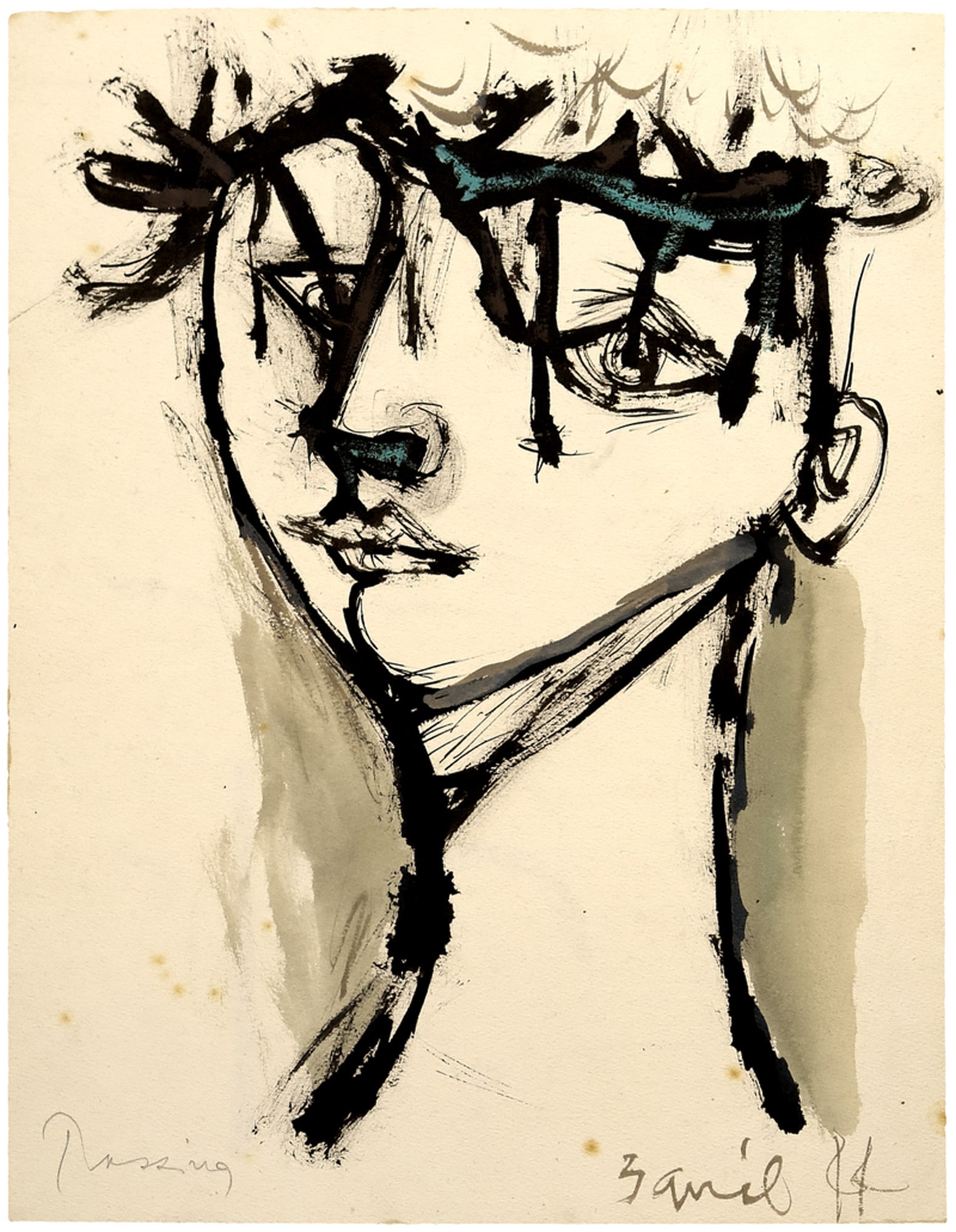

Untitled, 3 April 1944, Ink on paper, 31,7 x 24,6 cm., Private Collection

Yes, if nothing else goes wrong, I’ll shoot myself after I finish this recording. I will put the Lupara’s cut barrel against my insatiable mouth and pull the trigger. My salvation depends on it.

I wonder what the green-and-white painted wall behind me will look like.

I wonder what they will think when they find me. Will they believe me when they listen to this recording? Will they search for Rıza Bey? Is there another wolf here? Will he try to stave off his hunger as he looks at my face, all blown to pieces?

I don’t know.

Written by Galip Dursun

Translated by g yayın grubu

Among the most interesting themes in the oeuvre of Prassinos are cypresses, trees, and Turkish landscapes. The cypress woods in Üsküdar he saw every time he stepped out on the terrace of their house in İstanbul or the trees in Petits Champs must have been strong images of childhood for Prassinos.

About a year ago, Ela was dead for seven minutes. Death had come to her as she was watching her younger brother play gleefully in the sandpit at the park. A sudden flash that washed her world with a burning white light, a merciless roar resembling that of a monster…

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)