29 January 2016

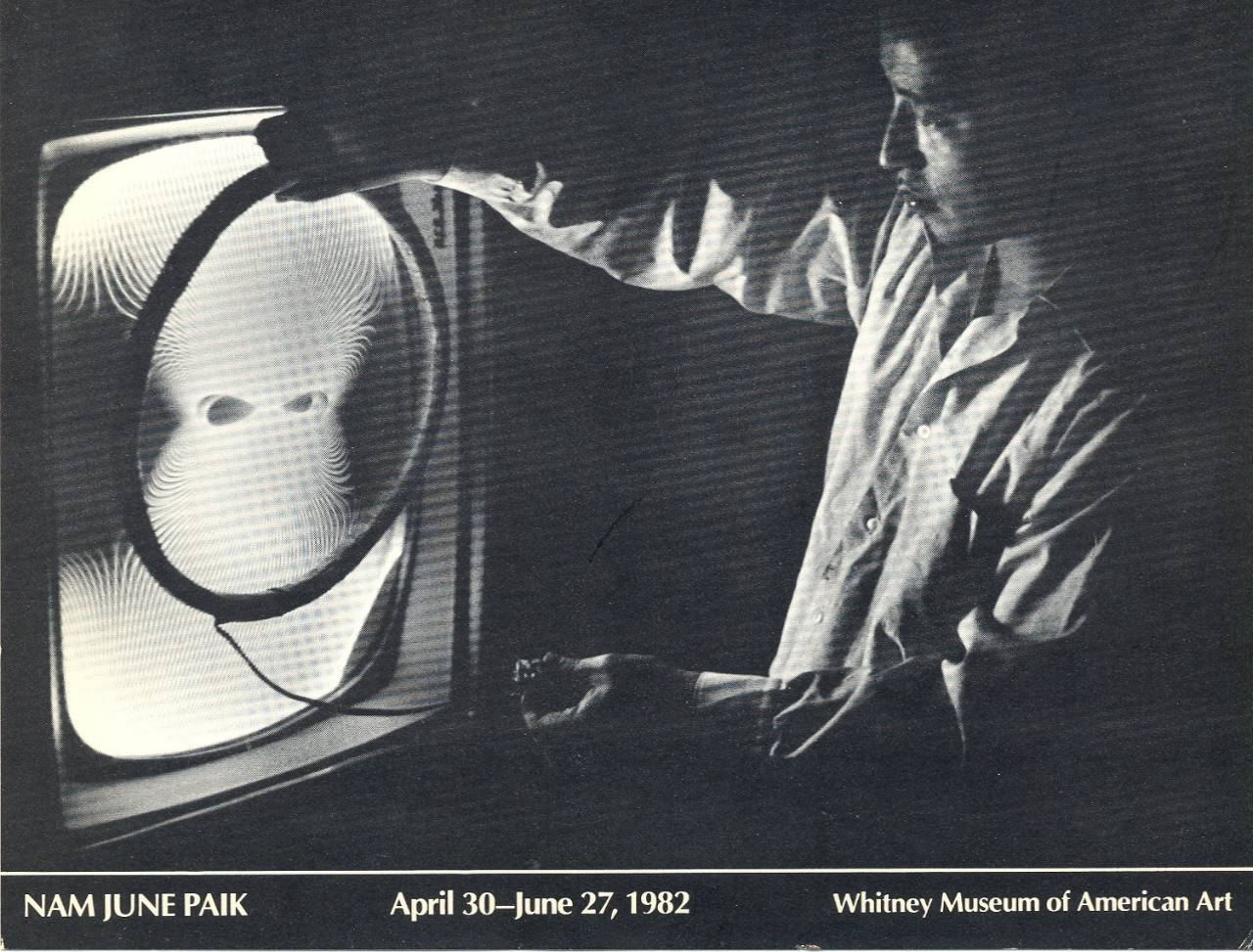

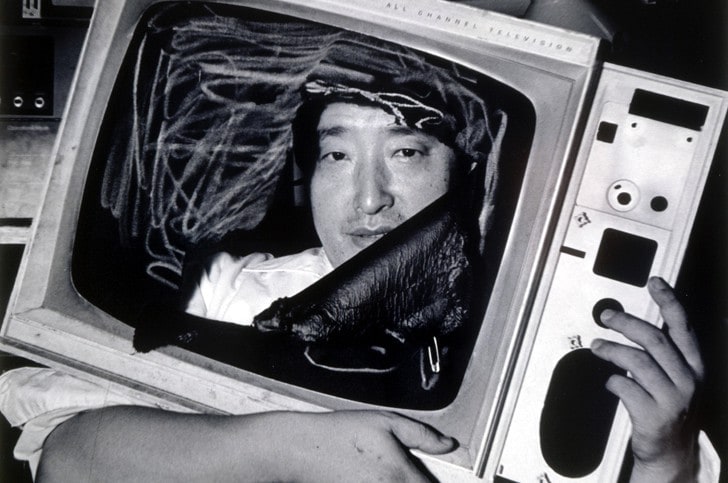

Nam June Paik was video art’s pioneer (1932 –2006). It is interesting that while Warhol and Nameth were experimenting with psychedelic happenings that combined rock, film and performance, the video art pioneers Nam June Paik, Stephen Beck, Eric Siegel and Steina Vasulka were researching in a similar direction.

With its specific links to to pop music and subsequent influence on the aesthetics of the music video in the transition from the 1960s to the 1970s, one of the most significant works in Nam June Paik’s vast production is Beatles Electroniques, made in collaboration with Jud Yalkut, which is presented as part of the exhibition This is Not a Love Song: Video Art and Pop Music Crossovers. This three-minute piece in black and white and color corresponds aesthetically to video art’s early period, when artists like Wolf Vostell and Paik himself showed an aggressive attitude, debunking the media icons that television had helped create. In this video Paik appropriates television images of performances by The Beatles and subjects them to an aggressive process in which sound and visuals are destroyed.

The myth-busting nature of this video is made even more meaningful by the fact that it coincides in time with the painful period when the band was breaking up. In fact, they made their separation official just a few months later. In Beatles Electroniques, Paik uses electromagnetic media to improvise with images of the group, distorting them until their faces disappear under the cathode texture. At the same time, the music is ‘corrupted’ by juxtaposing over the original song an electronic piece entitled Four Loops created by the composer Ken Werner out of snatches of sound from the same song altered by means of a synthesizer.

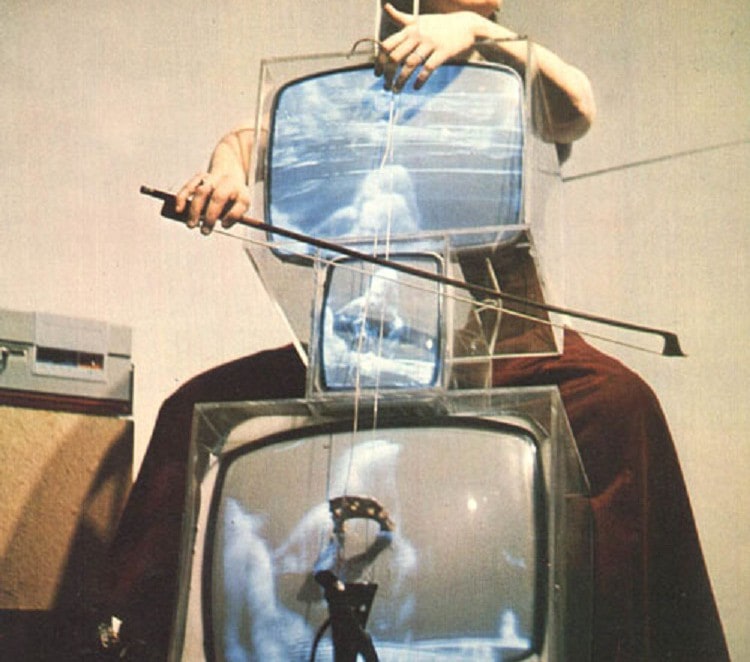

Four years later, Nam June Paik – in collaboration with John Godfrey – presented one of his most influential works, Global Groove, an ‘audio-visual pastiche’ which effectively deconstructs the language of television formats of the time, thereby becoming a landmark in video art. Global Groove forecasts concepts like zapping (so characteristic of the initial period of MTV), globalization and the overall saturation of the media. Applying an aesthetics typical of a pop hallucination, Paik mixes rock dancing – the video starts off unforgettably with Devil With a Blue Dress by the Detroit Wheels –, Japanese commercials, performances by John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Allen Ginsberg, Korean traditional dances, distorted images of President Nixon and the emblematic image of Charlotte Moorman playing her TV Cello. The term ‘Global’ in the title alludes directly to McLuhan’s Global Village and anticipates what would later happen when all the countries in the world would be connected to each other by cable television, while the term ‘Groove’ has clear musical connotations then linked above all to jazz and soul. In an interview with Jean-Paul Fargier, Paik explains that he had chosen the term ‘Groove’, used by New York jazz musicians to ‘denote the way the senses are blunted of those who abuse jazz as if it were a drug’ (Jean-Paul Fargier, 1986). The musical roots of video art were therefore clearly exposed in his early works.

Four years later, Nam June Paik – in collaboration with John Godfrey – presented one of his most influential works, Global Groove, an ‘audio-visual pastiche’ which effectively deconstructs the language of television formats of the time, thereby becoming a landmark in video art. Global Groove forecasts concepts like zapping (so characteristic of the initial period of MTV), globalization and the overall saturation of the media. Applying an aesthetics typical of a pop hallucination, Paik mixes rock dancing – the video starts off unforgettably with Devil With a Blue Dress by the Detroit Wheels –, Japanese commercials, performances by John Cage, Merce Cunningham and Allen Ginsberg, Korean traditional dances, distorted images of President Nixon and the emblematic image of Charlotte Moorman playing her TV Cello. The term ‘Global’ in the title alludes directly to McLuhan’s Global Village and anticipates what would later happen when all the countries in the world would be connected to each other by cable television, while the term ‘Groove’ has clear musical connotations then linked above all to jazz and soul. In an interview with Jean-Paul Fargier, Paik explains that he had chosen the term ‘Groove’, used by New York jazz musicians to ‘denote the way the senses are blunted of those who abuse jazz as if it were a drug’ (Jean-Paul Fargier, 1986). The musical roots of video art were therefore clearly exposed in his early works.

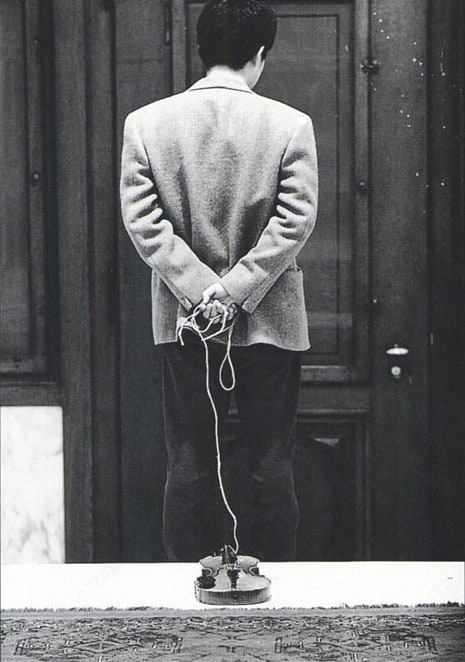

One of the works in the exhibition, Guitar Drag by Christian Marclay, also makes a reference to a performance of Nam June Paik that dates to 1961: Violin to Be Dragged on the Street. Today, Nam June Paik and his works continue to be an inspiration for artists, especially for the ones who work with video.

This is Not A Love Song: Video Art and Pop Music Crossovers took place at the Pera Museum between 25 November 2015 - 07 February 2016.

In 1962 Philip Corner, one of the most prominent members of the Fluxus movement, caused a great commotion in serious music circles when during a performance entitled Piano Activities he climbed up onto a grand piano and began to kick it while other members of the group attacked it with saws, hammers and all kinds of other implements.

Between 1963 and 1966 Andy Warhol worked at making film portraits of all sorts of characters linked to New York art circles. Famous people and anonymous people were filmed by Andy Warhol’s 16 mm camera, for almost four minutes, without any instructions other than ‘to get in front of the camera’.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)