19 April 2023

“All the world’s a stage…”

William Shakespeare

We, by which I mean some of my classmates and I, knew about Paula Rego. I’ll have to admit, I didn’t know where Rego was from or even where in Europe Portugal was. I thought she was English. Let me tell you how I first heard the very un-English sounding name “Paula Rego”: Next to the school (The Slade School of Fine Art, UCL, London) building, there was a salon called “Housman” where only faculty members could enter. In terms of comfort, it was reminiscent of airport VIP lounges. While all of us (men included) were having crises of hysteria at the studios, our teachers, all competent artists themselves, would gather at the Housman to chat and drink. Not knowing how to bridge the distance between our embarrassing beginnings and this magical salon was its own conundrum. In the end, we won our teachers’ favour in some way or another and one day, lo and behold, we found ourselves drinking wine at Housman at their invitation. In the middle of the salon was a wall, and on the wall there was a painting visible from every possible angle. The painting featured faces looking in different directions, colourful square forms, and a sense of the Mediterranean. I never looked up the artist after learning her name that day. That was a big mistake.

Maria Paula Figueiroa Rego was awarded the “Summer Composition” with this painting (Under Milk Wood, 1954) that she made when she was a student at my school. She would later go on to say that the most important moment in her life was receiving the award when there were so many talented painters at the Slade, according to the documentary by her son Nick Willing included in the exhibition. In the painting, she depicted the kitchen of a typical Lisbon house in her home town Portugal. Her grandmother’s house where she spent most of her early childhood had a similarly busy and lively kitchen. Rego loved spending time in that kitchen. I didn’t know these details then, but the influence of childhood memories on Rego paralleled my own experience. Longing for home would also become a theme in my paintings, and in the future, I would also win the Summer Composition award with a painting of my suitcase, packed and waiting, watching me over my wardrobe.

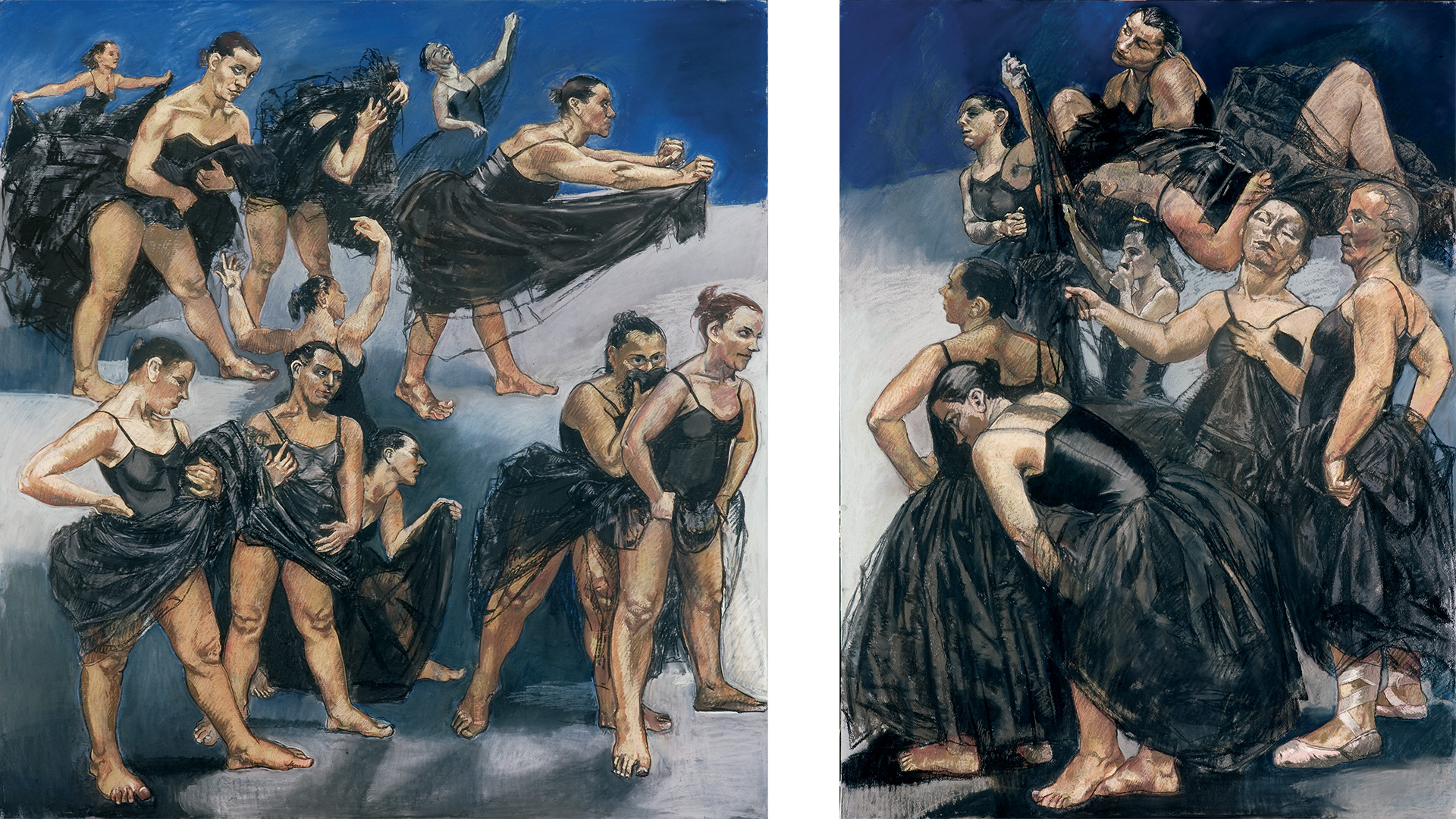

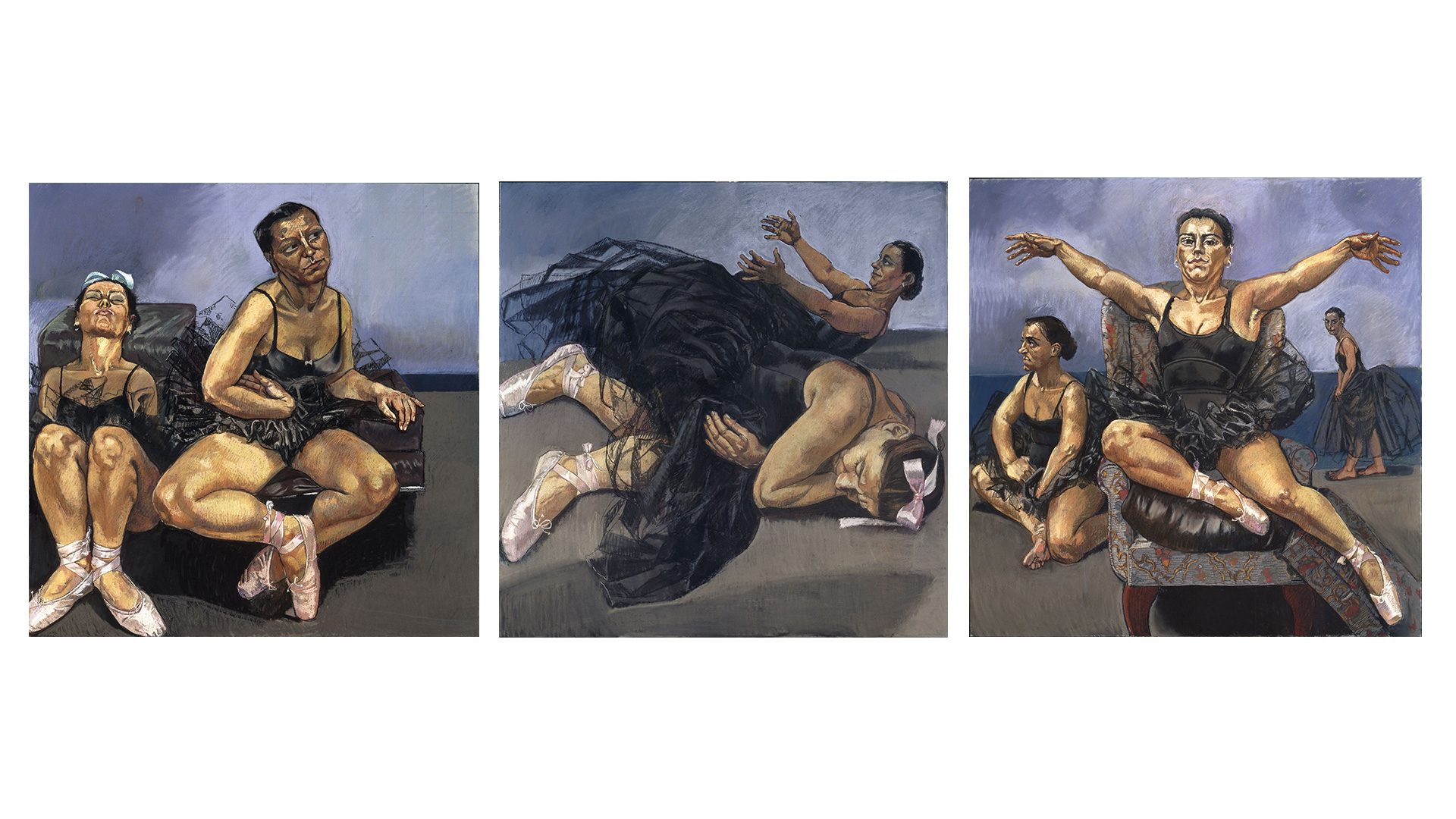

I came across Paula Rego’s works for a second time in London in 1996, at the Hayward Gallery exhibition Spellbound. Here, Rego showed 20 large paintings based on Walt Disney’s animated film Fantasia. There is a scene in Fantasia where ostriches dance. In the paintings, the ostriches were replaced by giant women. These women were truly ugly, one didn’t want to glance in their direction. They were too inelegant to be dancers. The surface was too crowded too. Arms and legs were bursting out of black tutus, filled in with lines over lines of pastel crayons. We were taught to look at beauty. What was this all about? I was ashamed of my womanhood, overwhelmed, and I couldn’t stand in front of these paintings for long. All I can say is that they were strong, very, very strong. I was still behind, and the paintings were so much ahead.

There, Paula Rego remained for me. Years went by. I graduated and went back to Turkey. I went on with my life, I painted. I opened exhibitions. In the meantime, Turkey opened up more and more as well. There were still atrocious incidents happening here and there, but it was the kind of thing that could happen anywhere. Then one day, Turkey started closing up. We didn’t notice at first. We still thought we were opening. Alas, the cynics were right, and contrary to what was promised, violations of human rights (women’s rights most of all), started to surge alongside a new conservatism. Negotiations for Turkey’s accession to European Union stalled. The people were divided in two while the country’s politics changed day to day. Istanbul’s European face was left unprotected, shivering. Lip service was given to "historical reckonings" and "blessings in disguise," but the government kept increasing its disproportionate force on all dissent. It became more and more difficult in this climate to breathe, to think calmly and humanely, to call for equality, or to find balance.

Why am I talking about all this? Because at this point of the story, I ran away to Portugal! This same peaceful corner of the earth that I found refuge in to paint was where Paula Rego, who loved her grandmother’s kitchen, ran away from to paint. I was only two years old when Paula Rego left Portugal for Great

The place I got to was Paula Rego’s inescapably small homeland (although she would always say that she was native to her studio). Not even a century had passed since under the leadership of António de Oliveira Salazar, Portugal had for forty to fifty years, extreme poverty, numerous human rights violations, and war casualties so severe during its colonial withdrawal that it ultimately caused the government to collapse. As it goes everywhere else, some people exploited the authoritarian regime and prospered.With the rise of the political right, the influence and oppression of the church also soared. Men and women weren’t equals in the first place; women couldn’t vote or have bank accounts. Under fascism, forms of oppression by men to women, women to women, and mother to daughter multiplied. Everything was censored, behavioral restrictions increased.

And so it was in the Portugal of 1935 that Paula Rego was born into, who observed firsthand the effects of the regime, especially on women. At 16, with her father’s support, she escaped from her prison (in her own words) and started her painting education in free London. It was many years before she received a tidy income from her paintings, so to finance her art she would teach painting and get research grants.

Nevertheless, Paula Rego didn’t forget where she came from. She always lived under the influence of Portugal’s sociopolitical climate, the church, and her grandmother’s counsel. With the happenings in Portugal as a foundation to her paintings, she powerfully added her own experiences to establish dramas often involving families and lovers.

In these dramatic scenes, she includes or refers to grotesque characters from Portuguese folk tales. Some of these stories she remembers from listening to her grandmother’s tales, but most come from the research she conducted later through the Gulbenkian grant. Her inspirations go beyond the Portuguese culture: Her field of study also encompasses short stories by Spanish, Italian and French authors, fables, Biblical stories, and classical, well-known fairy tales that can be taken as advice for young girls, like Little Red Riding Hood or Bluebeard. Based on these stories, she meticulously designs tableaux vivants, or costumed and detailed ‘living pictures’, to set up the foundation to her paintings. She sews dolls and different animals in various sizes to substitute for her characters. For live painting sessions, she chooses her models from within her family or London's Portuguese expatriate community. Even though the story doesn’t take place in Portugal, Rego inserts a coastal city in the painting background. This is often Ericeira, where she lived with her family. Sometimes it’s Estoril, a common destination for refugees and spies who migrated to America from Europe during World War II.

Considering her paintings’ progress step-by-step since the 1960s, we can see that contrary to Slade tradition, Paula Rego, with a few exceptions, initially avoided oil colour and realism. She worked on paper or canvas with collage or acrylics. In her early works, she haphazardly cut and pasted childishly painted figures with the influence of the Jungian psychotherapy she was in to treat her manic depression, Miro, and her newest discovery Dubuffet. These works are mostly criticisms of the Salazar regime. In these paintings, the figures are almost indiscernible, and we are guided mostly by their titles: Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, 1960 (p.76) Exile (1963), The Imposter, 1964, (p.80) Black People (1964), When We Had a House in the Country We’d Throw Marvellous Parties and then We’d Go Out and Shoot Black People, 1961, (p.78-79). The last is a criticism of Salazar's war against the liberationists of Portuguese colonies Mozambique and Angola. The exhibition also includes an embroidered tapestry depicting Quibir, a 16__ century battle when the Portuguese Empire was gravely defeated while trying to expand their territories, and their young king disappeared. This work can also be considered anti-war. During these early years Rego followed and used art movements such as surrealism (automatism), expressionism, and art brut to confront Portuguese history and culture.

In the 1980s, we can see that Rego adopted a more traditional and controlled approach to lines and figures, structuring her paintings inspired by folk tales, fairytales, novels, and plays with more clarity. In this era, psychosexual mischief, dramas, sexist power plays, and relationships of addiction took center stage. She wanted to turn any kind of hierarchical relationship on its head. In her paintings, men are drunk, lazy, and cowardly creatures who, needing protection, lie on women’s laps (during her childhood, Rego often strived to console her father, who was, like herself, depressed). The women, on the other hand, can be as merciless as they are submissive, and therefore survive.

Rego’s biggest inspiration for these narratives is Victor Willing (1928–1988), the Slade's wunderkind painter, where she met and fell in love with him. The charismatic Mr. Willing started his relationship with Rego while still in his first marriage, and kept philandering even after marrying Rego. All these affairs later found a place in her compositions. Yet everything changed in 1966 when Paula Rego’s father passed away and Willing was diagnosed with MS (multiple sclerosis). In time, they lost all their assets in Portugal and moved to London. After starting to paint again in the 1980s, Willing produced works that made him a sudden roaring success and opened an impressive exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery. He was then unfortunately bound to a wheelchair. His health quickly worsened after, and he was confined to bed. In this period of extreme hardship, Rego took over her husband’s care and she struggled with the natural feelings of anger and resentment towards his illness. She also battled dilemmas and desperations so strong that they brought on Rego’s own extramarital relationships. After Willing’s death at 60 in 1988, she could only reckon with her past through painting. Rego was now a express the complexity of her inner struggles, conveying an inner state thoroughly analyzed through reenactments. Like a novelist, she invited the viewer to look over th painter who knew how to e good and the bad of her character and empathize. The paintings where she depicted herself as a little girl and her husband as a dog or fox drew lots of attention in London, and the big-time artists’ gallery Marlborough made her an offer. Rego never had financial difficulty again.

This post-mortem exhibition at Istanbul’s Pera Museum, curated by Alistair Hicks, represents Paula Rego’s life story with a rich and powerful selection. It’s a wonderful opportunity for an introduction to Rego for those who haven’t met her art before.

Chronologically, Rego discarded perspective in the earliest paintings of the exhibit. These works are reminiscent of graphic novels. The events don’t have beginnings or ends. They are timeless. Among these, Red Monkey Beats His Wife, 1981, (p. 84) and Wife Cuts off Red Monkey’s Tail (1981) draws from fascism-based malignancy, while also depicting the impact of both Willing and Rego’s extramarital affairs. Pregnant Rabbit, 1981, (p. 85) recounts the shame that comes from a pregnancy out of wedlock, unfit for the authoritarian regime's notion of the ideal family (Willing was still married to his first wife when Rego was pregnant with their firstborn). Titled coherently, Aida, 1983 (p. 86) and Falstaff, 1983 are compositions inspired by Giuseppe Verdi’s operas. Her love for the opera was passed on to Rego by her father. Rego worked on these large-scale paper works laid down on the ground and from top to bottom, in order, just like preparing the storyboards for a future film. The Vivian Girls in Tunisia, 1984 (p. 88) is based on Henry Darger’s imagination, yet the depicted scene doesn’t exist in Darger’s story. Rego’s painting shows the female characters in an intergenerational argument, depicting mothers ‘eating’ their daughters. In the mid-80s, the increasingly large, colorful, and almost surreal paintings were replaced by an uncanny desolation with her husband’s approaching death. Untitled , 1987, and Snare, 1987 (p. 113) seem like a warm-up to her Dog Woman series in the 90s. Preparing to part with Willing, Rego was confronting her own desperation and the illness that took her husband away.

There are two more paintings included in the exhibition before she abandoned the brush and switched to pastels in 1994. One of them is Wide Sargasso Sea, 1991 (p. 114-115) and the other The Artist in her Studio, 1993 (p. 116). These two paintings are complete opposites. The first painting adopts its name from the Jean Rhys novel. It refers to Bertha Antoinetta Mason (Edward Fairfax Rochester’s wife, whom he kept in the attic), a character from Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre, and her life in Jamaica before coming to England and being trapped in Thornfield Hall. The painting illustrates a group of listless people spread out on the veranda of a large house, seemingly uninterested in the extreme loneliness and confinement that awaits Bertha at Thornfield Hall. The house resembles the Rego residence in Ericeira, but the costumes are more reminiscent of the book. As the novel is the story of the despair and torment that causes the heroine to go mad, Rego's painting might be objecting to the suffocating dysfunctionality of the upper-class family life, or a Portugal stranded inside its own horizons. The second painting is the most artistically competent work Rego produced after completing her artist-in-residence program at the National Gallery. We see the painter (she used Lila Nunes as her model) at the center of her own universe, in a pose independent and masculine. This painting, full of confidence, along with all the sketches, drawings, and prints dated 1987-1999 included in the exhibition, are indicators that Paula Rego has entered the mature stage of her artistic career. Her hand was now altogether strong, capable enough to achieve the clear lines and figuration she needs to convey her stories.

As soon as Rego started using pastels (she also plastered her papers to aluminum plates, fortified for impact), she was able to transmit all the accumulated suffering and anger to the surface. Now she was calling everyone to account for the injustice, speaking like a woman, defending women’s rights. Untitled No. 4, 1998 (p. 138) is part of the Abortion series which she started as a reaction to the referendum decision (the number of voters was too low) to reject a law that would allow for legal abortions in Portugal. Just like anywhere else in the world, school aged girls in Portugal who didn’t have access to legal abortion were forced to try illegal ways, risking their lives while struggling with the demoralization. Even though Portugal had attained democracy thanks to Mário Soares and the Socialist Party, they would have to wait until 2007 for the law to legalize abortion. To increase their circulation, Paula Rego converted her pastels into etchings. These bold prints displayed models in school uniforms right before or right after an abortion; and they were served to the public by Portuguese magazines and newspapers in advance of the second referendum. The general opinion is that they were crucial in informing the public and changing opinions. In Turkey, on the other hand, women are given the legal right to get a voluntary abortion until week 10 of the pregnancy by the Family Planning Law No. 1983. Unfortunately, the increasingly conservative atmosphere also affects the healthcare system. Even though it doesn’t have any legal foundation, free of charge abortions in public hospitals slowly vanished, and illegal practices gained currency. It is therefore very important that we keep Paula Rego’s courage and leadership in mind right now. Rego has set a very high standard with these works, but her extremely dismaying etching series on female circumcision sets them even higher. We ran into them so abruptly and I had so many questions from my 8-year-old that I had to explain the significance of these works. That worked out well!

Without digressing much further, it’s time to go back to the Dancing Ostriches series (1995, not included in the exhibition) and look at them again. No, I don’t find these paintings shameful at all. Now, 26 years later, the women don’t seem ugly either. They seem only familiar. They are absolutely ridiculous, but they are actors in a parody anyway. In this sense, I think they connote realism and acceptance. The women (even though I know one woman modeled almost all of them) keep playing their roles persistently, even relentlessly. This is not a rehearsal, but it’s almost impossible to see this incredible performance on stage. When it’s combined with Rego’s pastels, we understand that we’re up against images that can only be conveyed through paintings. And of course, on the street, at home, in the workplaces… These women are everywhere.

Leylâ Gediz

While Paula Rego belatedly was recognised as one of the leading feminist pioneers of her age, little has been written about her exploration of fluid sexuality. Indeed the current of sado-masochism in her drawings and paintings, has tended to encourage an understanding as a classic clash between the patriarchy and exploited women.

Félix Ziem is accepted as one of the well-known artists of the romantic landscape painting, and has been followed closely by art lovers and collectors of all periods since. He had a profound influence on generations of artists after him, and was the first artist whose works were acquired by the Louvre while he was still alive.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)