15 May 2015

The Vanity of Small Differences is a series of six large scale tapestries, completed in 2012, which explore British fascination with taste and class, and can be seen in the Grayson Perry: Small Differences exhibition. Inspired by the 18th century painter William Hogarth’s moral tale, A Rake’s Progress (1733), Perry’s tapestries follow the life of a fictional character called Tim Rakewell as he develops from infancy through his teenage and middle years, to his untimely death in a car accident. Through this progress, Perry analyses class mobility in Britain and gathers characters, places, and objects he encountered on his travels through Sunderland, Tunbridge Wells, and the Cotswolds for his Bafta-winning documentary series All in the Best Possible Taste with Grayson Perry (2012).

The tapestries are rich in both content and colour and depict many of the eccentricities and peculiarities associated with life in the United Kingdom, from interior design to British cuisine, political protest, and celebrity gossip. The title of the series refers to the small differentiating factors that allow us to understand which social group a person belongs or aspires to, such as choice of clothes, cars and hobbies. The composition of each tapestry also references early Renaissance religious paintings, and act to draw us into an art-historical as well as a sociopolitical exploration of modern life.

The Vanity of Small Differences was woven by Flanders Tapestries in Belgium. Perry’s drawings were translated into a computer programme that controlled the digital loom, and yarns were dyed to match the colours in the drawings. Upon the preparatory work including trial of several combinations of different yarns, weaves and tensions, each tapestry was made in a limited edition of six.

The Adoration of the Cage Fighters

“The Adoration of the Cage Fighters”, 2012. Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry, 200 X 400 cm. British Council Collection.

The scene is Tim’s great-grandmother’s front room. The infant Tim reaches for his mother’s smartphone – his rival for her attention. She is dressed up, ready for a night out with her four friends, who have perhaps already ‘been on the pre-lash’. Two ‘Mixed Martial Arts’ enthusiasts present icons of tribal identity to the infant: a Sunderland A.F.C. football shirt and a miner’s lamp. In the manner of early Christian painting, Tim appears a second time in the work: on the stairs, as a four-year-old, facing another evening alone in front of a screen. Although this series of images developed very organically, with little consistent method, the religious reference was here from the start: I hear the echo of paintings such as Andrea Mantegna’s The Adoration of the Shepherds (c.1450).

Text (in the voice of Tim’s mother):

‘I could have gone to Uni, but I did the best I could, considering his father upped and left. He (Tim) was always clever a little boy, he know how to wind me up. My mother liked a drink, my father liked one too. Ex miner a real man, open with his love, and his anger. My Nan though is the salt of the earth, the boy loves her. She spent her whole life looking after others. There are no jobs around here anymore, just the gym and the football. A normal family, a divorce or two, mental illness, addiction, domestic violence… the usual thing… My friends they keep me sane… take me out… listen… a night out of the weekend in town is a precious ritual.’

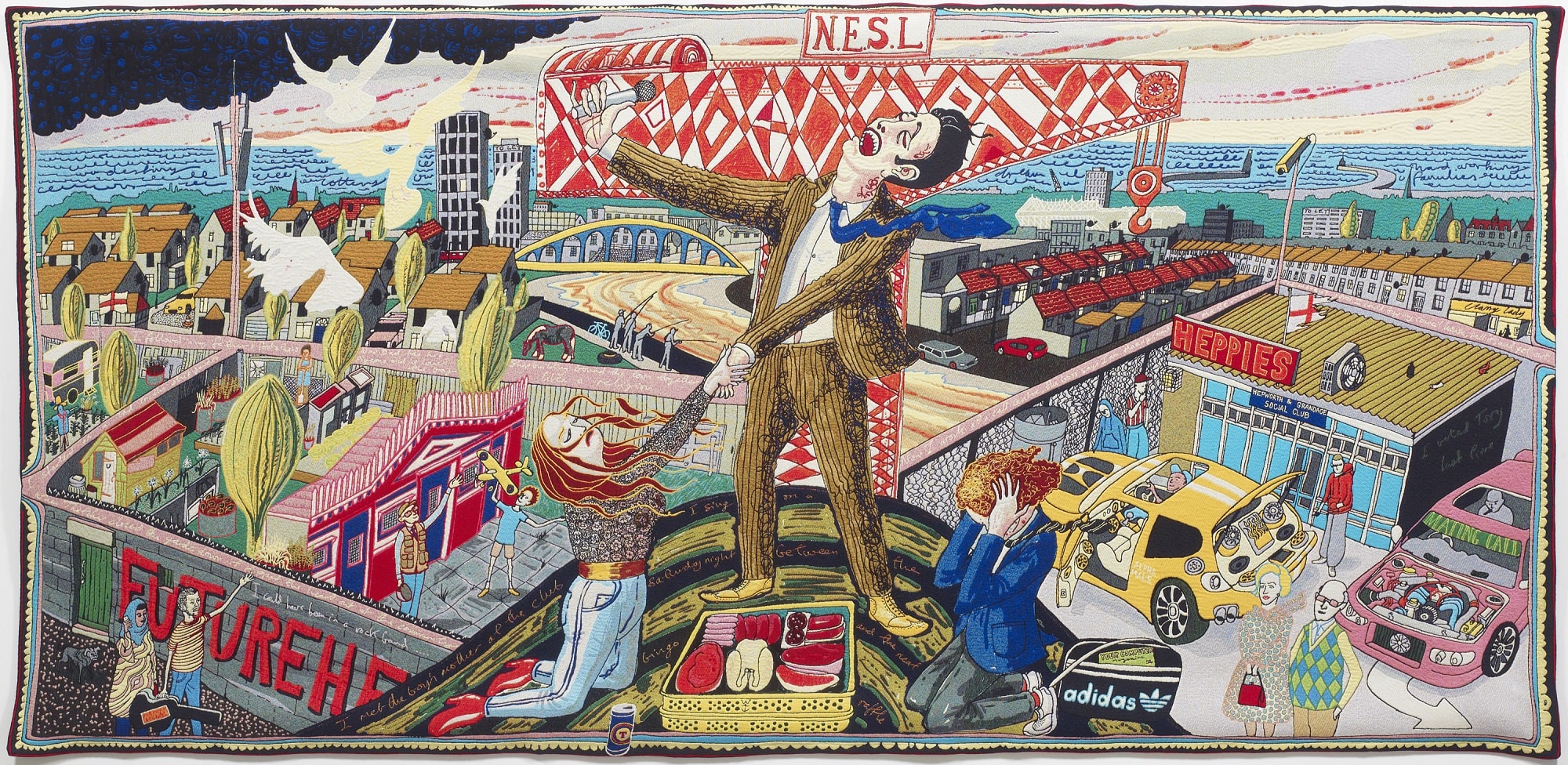

The Agony in the Car Park

“The Agony in the Car Park”, 2012. Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry, 200 X 400 cm. British Council Collection.

This image is a distant relative of Giovanni Bellini’s The Agony in the Garden (c. 1465). The scene is a hill outside Sunderland – in the distance is the Stadium of Light. The central figure, Tim’s stepfather, a club singer, hints at Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece (1512-16). A naively-drawn shipyard crane stands in for the crucifix, with Tim’s mother as Mary below it –once again in the throes of an earthly passion. Tim, in grammar school uniform, blocks his ears, squirming in embarrassment. A computer magazine sticks out of his bag, betraying his early enthusiasm for software. To the left, a younger Tim plays happily with his step-grandfather outside his pigeon cree on the allotments. To the right, young men with their customised cars gather in the car park of ‘Heppies’ social club. Mrs T and the call centre manager await a new recruit into the middle class.

Text (in the voice of Tim’s stepfather):

‘I started as a lad in the shipyards. I followed in my father’s footsteps. Now Dad has hid pigeons and he loves the boy. Shipbuilding bound the town together like a religion. When Thatcher closed the yards down it ripped the heart out of the community. I could have been in a rock band [above graffiti of Sunderland band The Futureheads]. I met the boy’s mother at the club. I sing on a Saturday night between the bingo and the meat raffle. Now I work in a call centre, the boss says I am management material. The money’s good, I could buy my council house, sell it and get out. I voted Tory last time.’

Expulsion from Number 8 Eden Close

“Expulsion from Number 8 Eden Close”, 2012. Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry, 200 X 400 cm. British Council Collection.

Tim is at university studying computer science, and is going steady with a nice girl from Tunbridge Wells. To the left, we see Tim’s mother and stepfather, who now live on a private development and own a luxury car. She hoovers the AstroTurf lawn, he returns from a game of golf. There has been an argument and Tim and his girlfriend are leaving. They pass through a rainbow, while Jamie Oliver, the god of social mobility, looks down. They are guilty of a sin, just like Adam and Eve in Masaccio’s The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden (c.1425). To the right, a dinner party is just starting. Tim’s girlfriend’s parents and fellow guests toast the new arrival.

Text (in the voice of Tim’s girlfriend):

‘I met Tim at College, he was Such a Geek. He took me back to meet his mother and Stepfather. Their house was so clean and Tidy, not a speck of dust… or a book, apart from her god, Jamie. She Says I have turned Tim into a Snob. His parents don’t appreciate how bright he is. My father laughed at Tim’s accent but welcomed him onto the sunlit uplands of the middle classes. I hope Tim loses his obsession with money.’

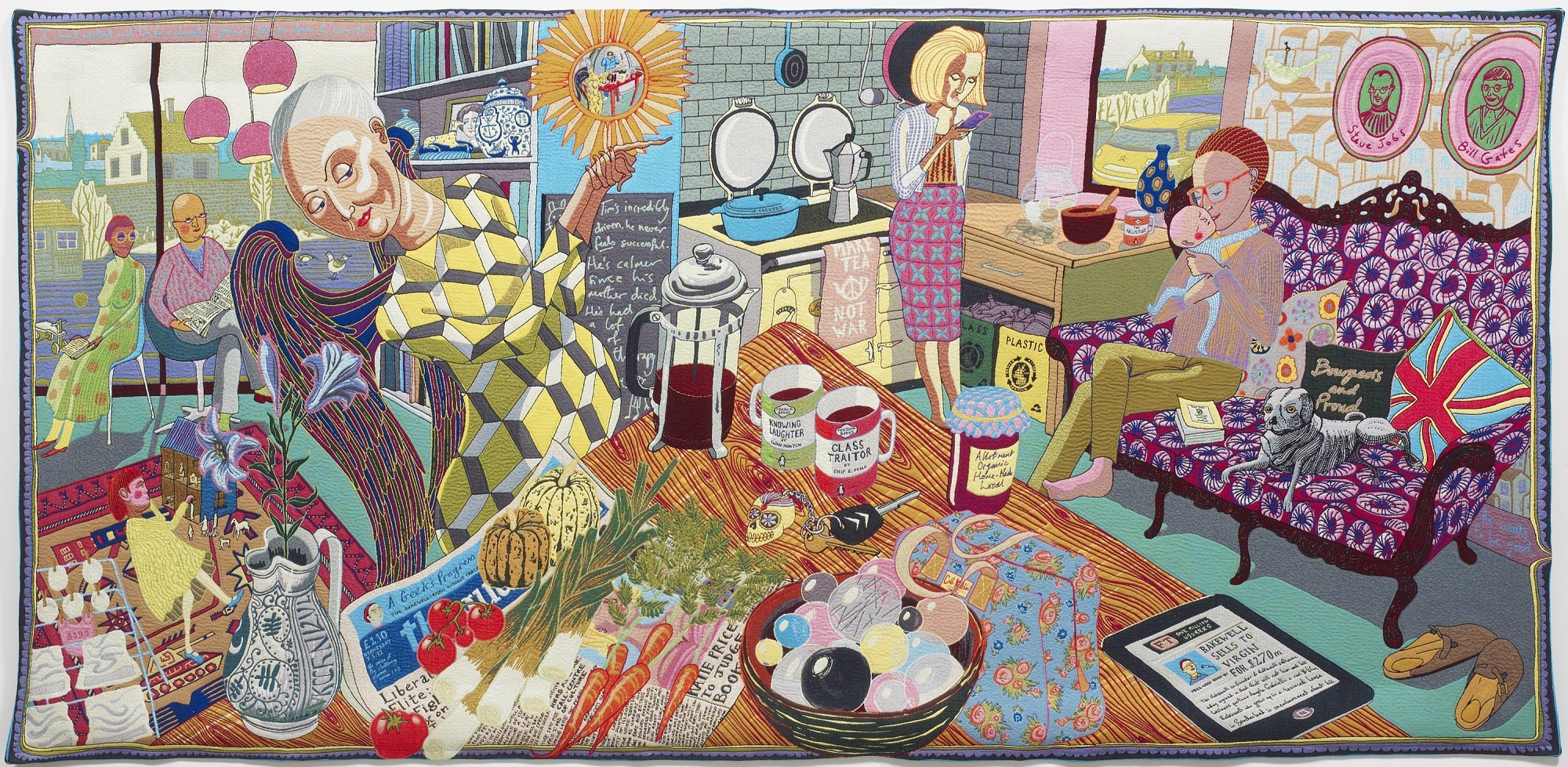

The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal

“The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal”, 2012. Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry, 200 X 400 cm. British Council Collection.

Tim is relaxing with his family in the kitchen of his large, rural (second) home. His business partner (in yellow) has just told him that he is now extremely wealthy man, as they have sold their software business to Richard Branson. On the table is a still life demonstrating the cultural bounty of his affluent lifestyle. To the left, his parents-in-law read, and his elder child plays on the rug. To the right, Tim dandles his baby while his wife tweets. This image includes references to three different paintings of the Annunciation by Carlo Crivelli (the vegetables), Matthias Grünewald (his colleague’s expression) and Robert Campin (the jug of lillies). The convex mirror and discarded shoes are reminders of that great pictorial display of wealth and status, The Arnolfini Portrait (1434) by Jan van Eyck.

Text (in the voice of Tim’s business partner):

‘I have worked with Tim for a decade, a genius, yet so down to earth. Tim’s incredibly driven, he never feels successful. He’s calmer since his mother died. He’s had a lot of therapy. He wants to be good.’

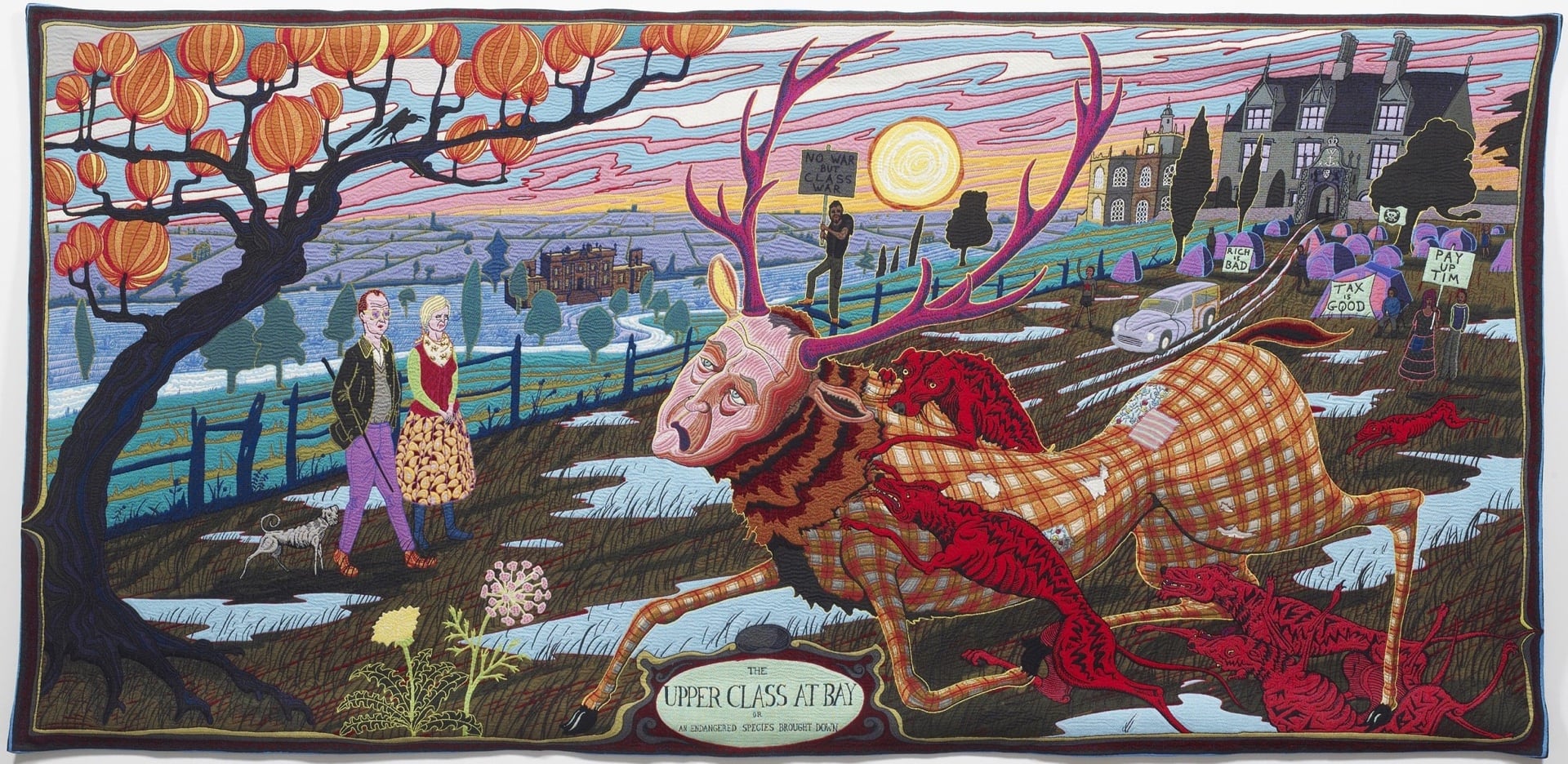

The Upper Class at Bay

“The Upper Class at Bay”, 2012. Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry, 200 X 400 cm. British Council Collection.

Tim Rakewell and his wife are now in their late forties and their children are grown. They stroll, like Mr and Mrs Andrews in Thomas Gainsborough’s famous portrait of the landed gentry (c. 1750), in the grounds of their mansion in the Cotswolds. They are new money; they can never become upper-class in their lifetime. In the light of the sunset, they watch the old aristocratic stag with its tattered tweed hide being hunted down by the dogs of tax, social change, upkeep and fuel bills. The old land-owning breed is dying out. Tim has his own problems; as a ‘fat cat’ he has attracted the ire of an ‘Occupy’-style protest movement, who camp outside his house. The protester silhouetted between the stag’s antlers refers to paintings of the vision of a crucifix above the head of a stag.

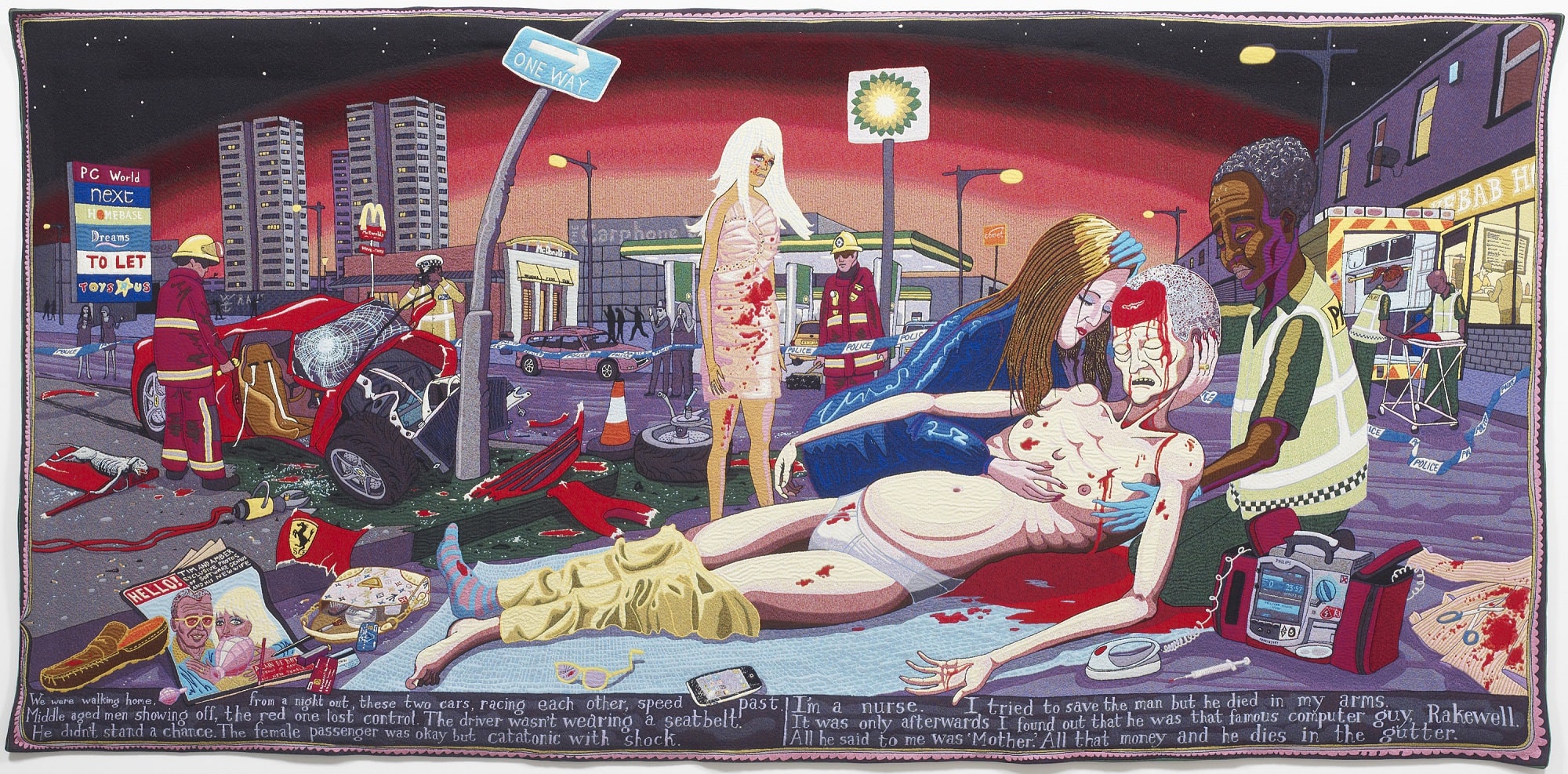

#Lamentation

“#Lamentation”, 2012. Wool, cotton, acrylic, polyester and silk tapestry, 200 X 400 cm. British Council Collection.

The scene is the aftermath of a car accident at an intersection near a retail park. Tim lies dead in the arms of a stranger. His glamourous second wife stands stunned and bloodstained amidst the wreckage of his Ferrari. To the right, paramedics prepare to remove his body. To the left, police and firemen record and clear the crash scene. Onlookers take photos with their camera phones to upload to the internet. His dog lays dead. The contents of his wife’s expensive handbag spill out over a copy of Hello magazine that features her and Tim on the cover. At the bottom of Rogier van der Weyden’s Lamentation (c.1460), the painting that inspired this image, is a skull; I have substituted it with a smashed smartphone, which refers back to the first tapestry in the series, where Tim reaches for his mother’s phone. This scene also echoes the final painting of Hogarth’s A Rake Progress (1733), where Tom Rakewell dies naked in The Madhouse.

Text (in the voice of a female passer-by):

‘We were walking home from a night out, these two cars, racing each other, speed past. Middle aged men showing off, the red one lost control. The driver wasn’t wearing a seatbelt. He didn’t stand a chance. The female passenger was okay but catatonic with shock. I’m a nurse. I tried to save the man but he died in my arms. It was only afterwards I found out that he was that famous computer guy, Rakewell. All he said to me was “Mother”. All that money and he dies in the gutter.’

Grayson Perry: Small Differences took place at the Pera Museum between May 13 - July 26 2015.

When regarding the paintings of Istanbul by western painters, Golden Horn has a distinctive place and value. This body of water that separates the Topkapı Palace and the Historical Peninsula, in which monumental edifices are located, from Galata, where westerners and foreign embassies dwell, is as though an interpenetrating boundary.

Following the opening of his studio, “El Chark Societe Photographic,” on Beyoğlu’s Postacılar Caddesi in 1857, the Levantine-descent Pascal Sébah moves to yet another studio next to the Russian Embassy in 1860 with a Frenchman named A. Laroche, who, apart from having worked in Paris previously, is also quite familiar with photographic techniques.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)