24 October 2019

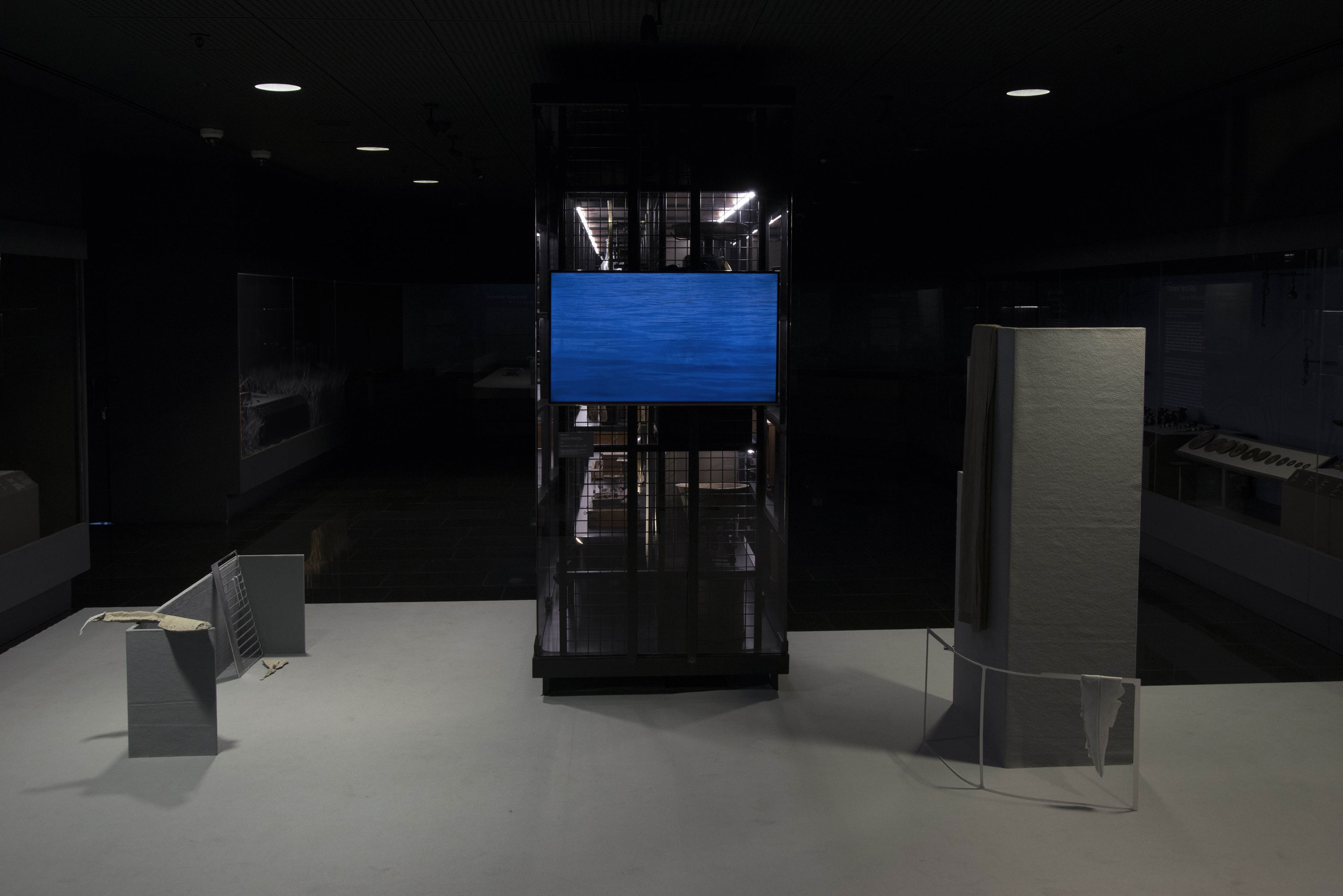

Inspired by its Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection, Pera Museum presents a contemporary video installation titled For All the Time, for All the Sad Stones at the gallery that hosts the Collection. The installation by the artist Nicola Lorini takes its starting point from recent events, in particular the calculation of the hypothetical mass of the Internet and the weight lost by the model of the kilogram and its consequent redefinition, and traces a non-linear voyage through the Collection.

Here’s an interview with Lorini. Feel free to leave your questions at the comments below.

Can you talk about For all the Time, for All the Sad Stones briefly?

For all the Time, for All the Sad Stones presents a nonlinear journey through Pera Museum’s Anatolian Weights and Measures Collection bringing together subjective and emotional states, and questioning the univocal approach to time and history. The work includes sound, moving image and sculptural objects. It is a site specific installation inhabiting the room that hosts one of the Museum’s permanent collections.

Both the video and the sculptural parts have been produced layering references coming from books and the Internet, merged with fragments of fictional dialogues inspired by dreams I had while developing the installation.

Can you elaborate on your research about the collection? What are some connections between the collection and the work?

The project was initiated quite spontaneously and in fact responding to the collection wasn’t a limitation but rather an expansion of the research I was developing when I started collaborating with the museum. Since the beginning, my fascination with the collection was not about the historical/archaeological value of specific objects, but more about the density of information, characters and moods they were evoking. I started conceiving it as a material accumulation of human trajectories and effort to define and control things, a restless attempt to relate to what is “out there”.

I think we find ourselves reconsidering specific models of thought relating to western culture, due to the impact of digital paradigms and, even more, due to the climate crisis we are facing. In a context, in which questioning an anthropocentric understanding of things became a necessity, a set of inevitable questions arises. This doesn’t only involve the human/nature or natural/artificial relationship, but it expands to a dualistic understanding of good/bad, past/future and in so the notions of history and time, meant as purely linear phenomena, start collapsing.

I engaged with the collection with these questions in mind, dealing with the objects as if they were something I found on the street or something I made myself, without fetishizing them, trying to avoid any hierarchical structure given by their age, origin or function.

It was really about falling in love with specific presences, textures and atmospheres.

What does the title refer to?

The title, For All the Time, for All the Sad Stones, brings together three different sources. It is partially and ironically quoting the metric system statement For All the Time, for All the People. The original statement, coined in the 19th century, clearly incorporates an anthropocentric optimism: the idea of creating a system of measures that could work for “everyone” and “forever”. I replaced “people” with “stones”, charging them though, with the humane feeling of sadness. In old Arabic sad has another meaning which is stone and it is the word used to define small glass weights stored in the collection’s archive. I decided to bring these references together creating a statement that was somehow addressing a post-anthropocentric scenario but at the same time triggering an emotional tableau.

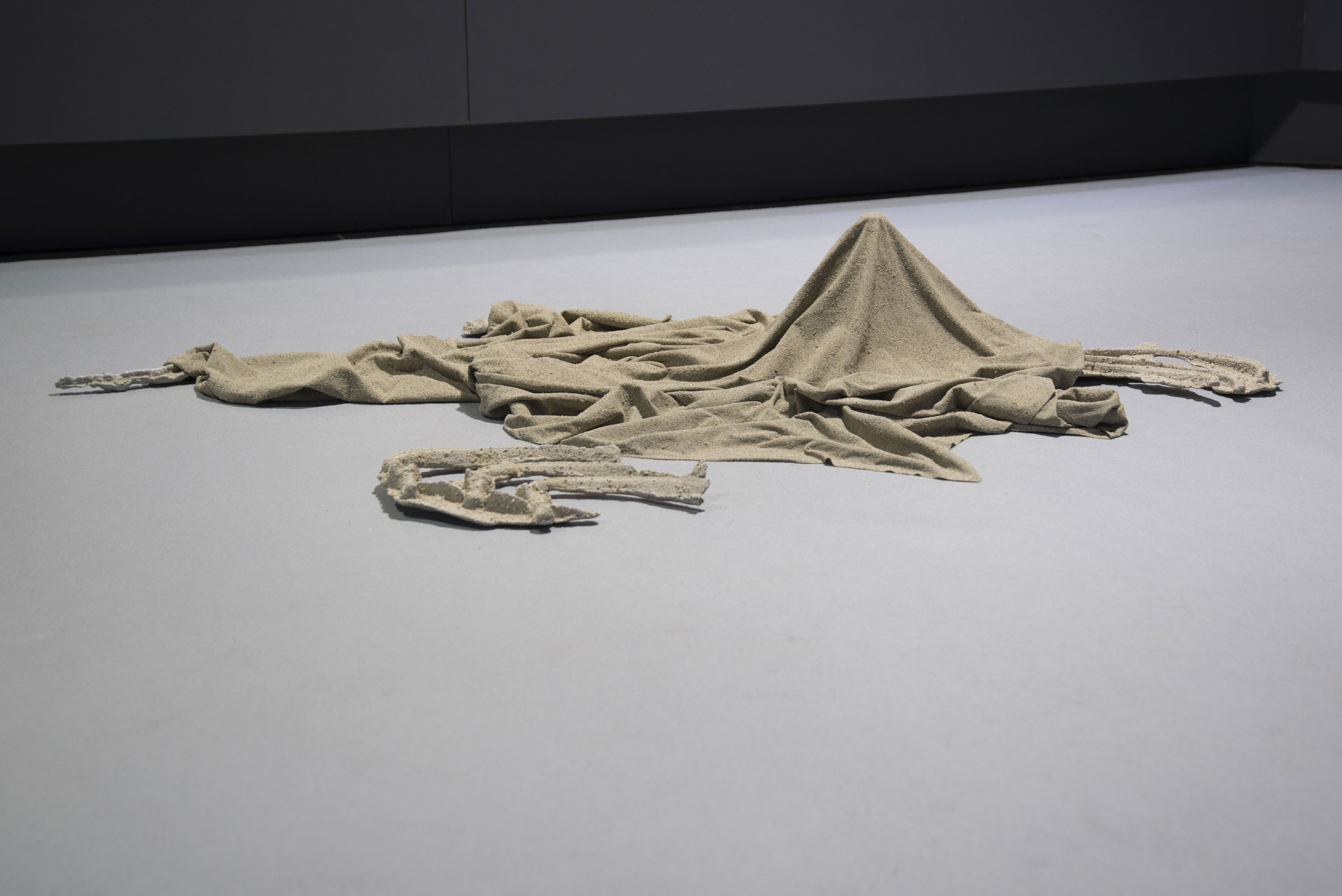

Can you elaborate on the choice of material? Why sand, silicone, aluminum and bones?

There are two materials that have been quite recurrent in my latest work and definitely present in the installation at Pera Museum: sand and deer bones. I started using sand a couple of years ago as a sentimental, romantic element, I was collecting in specific locations related to personal experiences and memories. That aspect, that still survives, embraced lately a more political and critical value. Sand is the third element on earth consumed by humanity: It is sold and stolen, capitalized and exploited. It is at the basis of any civilization but it is also the source used, in form of silicon, to produce all the chips sustaining our smartphones and laptops. Like ash, sand is the result of an erosion or consumption, it can move with winds, make things disappear or suffocate them. The use of deer bones is mainly related to the astragalus, a small bone present in paws of goats, sheep and hoofed ruminant mammals. It is a bone that holds the weight of the animal, dampening the stress, not only physical but potentially also existential, I like to see it as a sort of black box absorbing traumas. Many weights in the collection are shaped in form of astragalus. These little bones used to have religious value, they were used as dices and they are meant to be the first money ever used in humanity to exchange goods. In this sense I approached these bones as I did with sand; natural elements charged with economical yet spiritual aspects.

You usually work with sculpture and installation, what is the role of video and sound in this work?

Lately I have been interested in the possibility of creating environments rather than individual sculptures, focusing more on specific atmospheres than on clearly “recognizable” works. This process involves a research aspect which is very important for me. Given a specific context, like Pera Museum, I usually start navigating information and references quite horizontally, accumulating several directions, stories, images and written responses. This process usually merges with dreams I have and all these elements start exchanging and overlapping. I often end up with folders full of images, links and written texts that most of the time are not accessible in the final outcome of the work. This is why I have decided to work with video this time, I thought moving image could include in a more fluid way a set of background trajectories and layers of research otherwise difficult to transmit. The sound which is related to the video, but conceived as a soundscape for the entire room, is meant to be an immersive element, another element in the attempt of creating a habitat that can be felt rather than understood.

Pera Museum presented a talk on Nicola Lorini’s video installation For All the Time, for All the Sad Stones, bringing together the artists Nicola Lorini, Gülşah Mursaloğlu and Ambiguous Standards Institute to focus on concepts like measuring, calculation, standardisation, time and change.

In a bid to review the International System of Units (SI), the International Bureau of Weights and Measures gathered at the 26th General Conference on Weights and Measures on November 16, 2018. Sixty member states have voted for changing four out of seven basic units of measurement. The kilogram is among the modified. Before describing the key points, let us have a closer look into the kilogram and its history.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)