21 December 2015

Gatefold Sleeve Of The Frank Zappa’s We’re Only in It for the Money, 1968 Cal Schenkel, Verve Records

Gatefold Sleeve Of The Frank Zappa’s We’re Only in It for the Money, 1968 Cal Schenkel, Verve Records

I think it was Frank Zappa – though others claim it was Laurie Anderson – who said in an interview that ‘writing on music is much like dancing on architecture’. Such a biting comment was a way of telling certain smug music critics that no text is able to capture the energy and emotion generated by the experience of composing, playing or simply listening to music. In the same vein, nobody devoted to contemporary art is unaware that many artists fail to recognize themselves in reviews of their work published in a number of specialized journals, so it is understandable, to a certain extent, that both musicians and artists mistrust those of us who attempt to describe in black and white something as abstract as the values conveyed by a piece of music or a work of art that the reader may not have had the chance either to hear or contemplate.

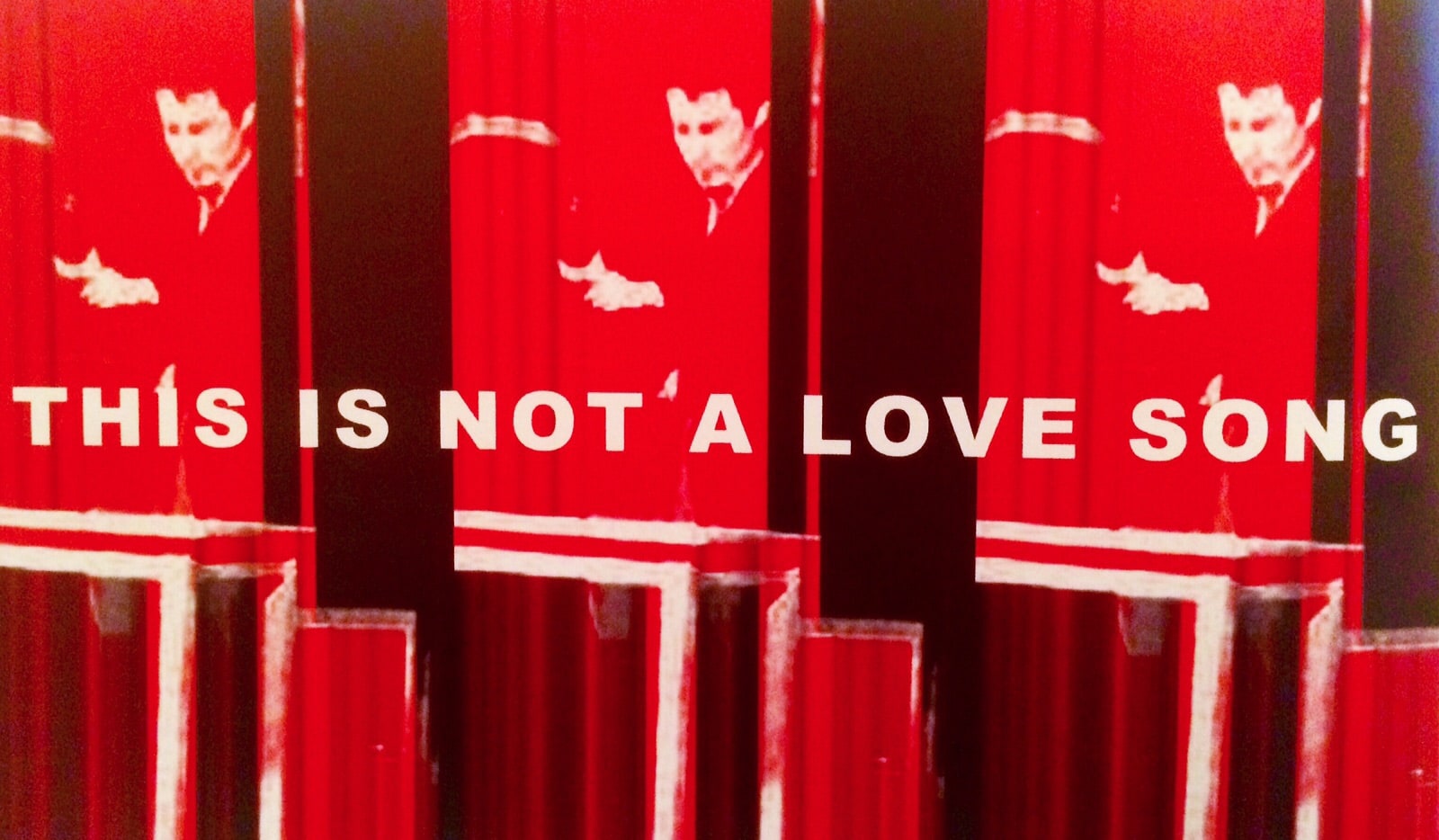

Largen and Bread , This is Not a Love Song (Character Appropriation), Vi̇deo, 2013, Courtesy of Javier Largen

Although I feel great respect for Frank Zappa, at least since that irreverent album came my way that cynically parodies the cover of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s under the title We’re Only in It for the Money, I should like to invert the scale of values underlying his provocative observation by declaring that one of the few things I find as pleasurable as listening to music is precisely talking about and discussing it… and that I have probably enjoyed myself and learned as much from visiting and organizing exhibitions as from passionately discussing and writing about works of art and artists. So, to carry on with this dialectical game and open a new discussion front, I have taken the liberty to bring up another famous quote, this one from Octavio Paz, for whom ‘architecture is frozen music’.

Fortunately, despite the fact that some people attempt to place barriers in the way of the promiscuous circulation of music and images in the web, the heterotopy of ‘dancing on architecture’ is almost possible today in media like the Internet where, apart from writing without publishing restrictions, you can link videos, download songs or link the website of the artist or the MySpace of the rock band whose music we cannot get out of our heads. But let me make it clear that I have absolutely no intention to attempt to resemble Nick Hornby, the British writer who in his excellent 31 Songs traced out a kind of autobiography through the emotional resonance his selection of popular songs carries. This Is Not a Love Song is above all a way of facing the arduous task of establishing a genealogy of the relationship between pop music and the visual arts from the sixties to the present day, placing special emphasis on those moments in which both genres exerted feedback on each other and moved in the realms of experimentation, utopia or the politically incorrect; all of which are values very familiar to Zappa who, incidentally, was not only an extraordinary musician but also a more than respectable experimental filmmaker.

Felix Curto

Felix Curto

Yo La Tengo, Photography, 2011

Courtesy of the artist

Text taken from F. Javier Panera Cuevas’ article in the exhibition catalogue for This is Not A Love Song.

In 1962 Philip Corner, one of the most prominent members of the Fluxus movement, caused a great commotion in serious music circles when during a performance entitled Piano Activities he climbed up onto a grand piano and began to kick it while other members of the group attacked it with saws, hammers and all kinds of other implements.

Nam June Paik was video art’s pioneer (1932 –2006). It is interesting that while Warhol and Nameth were experimenting with psychedelic happenings that combined rock, film and performance, the video art pioneers Nam June Paik, Stephen Beck, Eric Siegel and Steina Vasulka were researching in a similar direction.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)