30 April 2021

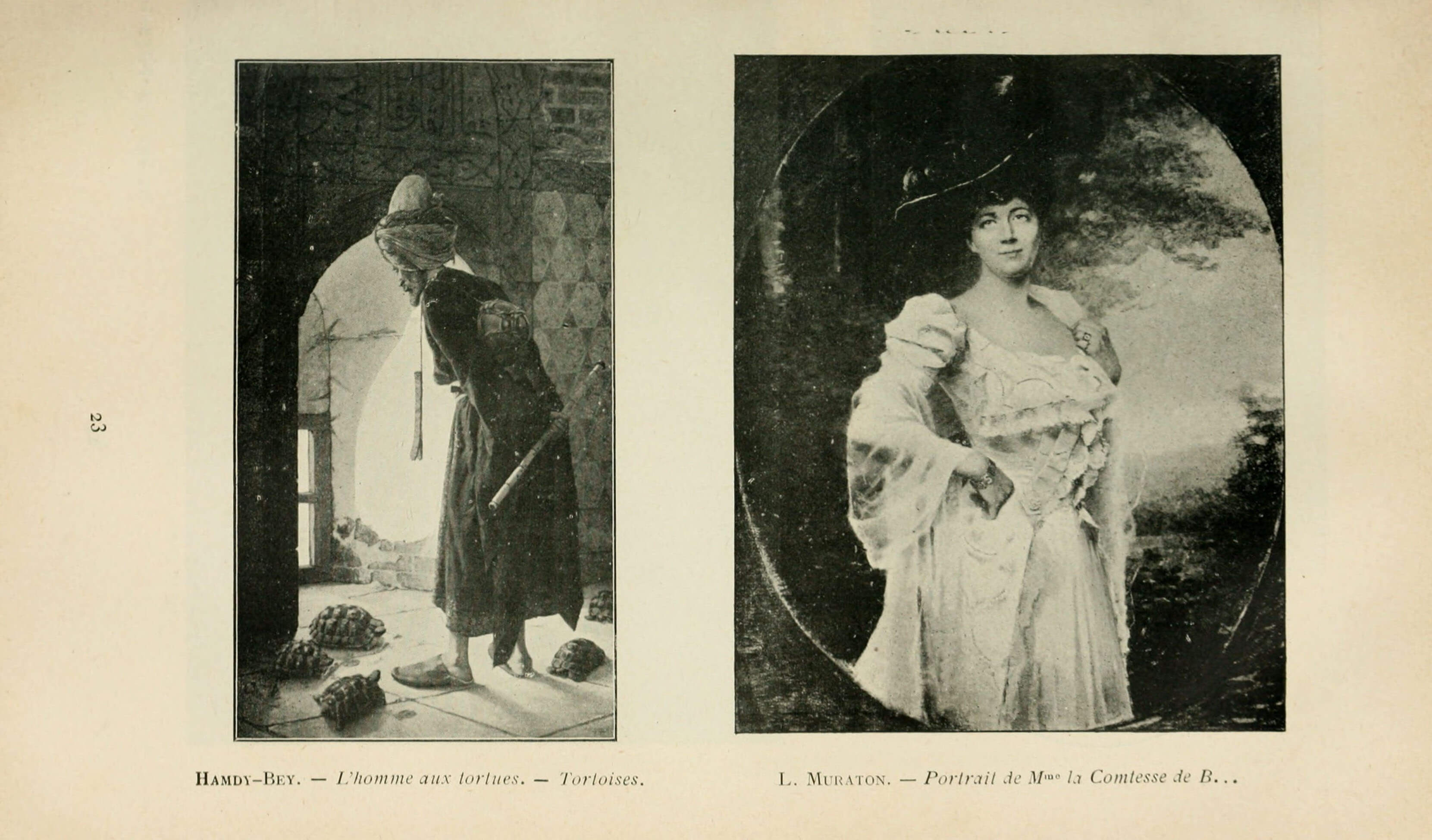

A Salon exhibition held in the Grand Palais in Paris on May 1, 1906 showcased an Ottoman painting. This was Osman Hamdi Bey’s famous “Tortoise Trainer”. The catalogue for the exhibition, managed by Ludovic Baschet, featured 1734 paintings and 845 sculptures (figs. 1, 2). Number 783, painted by “Hamdy Bey” was titled “L’homme aux tortues” (The man with tortoises) (fig. 3). Even though the initials of most artists’ last names were included in the descriptions, Osman Hamdi’s name was written as “Hamdy Bey”, probably as this was how he was recognized in France. The painting was also featured as an engraving in the middle pages of the catalogue and titled in English as “Tortoises”. The same catalogue also informs us that the museum opened at 8 am every day, except for Mondays, when it opened at 10 am, and remained open until 6 am the next day. The entrance fee was 10 francs on opening day and 1 franc on other days, expect for Sunday afternoons, when it cost 50 cents.

1. Cover page of the 1906 Salon exhibition catalogue.

2. Inner cover of the 1906 Salon exhibition catalogue.

This exhibition was the result of a long-standing tradition. Until the 20th century, this tradition went through many stages, inspired the creation of art criticism (which would go on to shape social taste in art), adapted to the political climate of its time, and finally, being the symbol of a higher authority, created its own opposition.

The page with Osman Hamdi Bey’s “Tortoise Trainer” in the 1906 Salon exhibition catalogue

The page with Osman Hamdi Bey’s “Tortoise Trainer” in the 1906 Salon exhibition catalogue

Salon exhibitions began in 1667 with the display of works of art created by the members of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture), as ordered by King Louis XIV, before becoming a significant part of Parisian life in the 18th century[1]. In the 17th century, these exhibitions consisted of unorganized events held in the Academy’s meeting rooms. Later they were taken outdoors, where they were displayed in the archways of Palais Royal. However, as we learn from a note taken by Mercure du France, artists had to withdraw their works early to minimize the threat of weather damage to their art, “before the curiosity of the public had been satisfied” [2]. In 1699, the exhibitions were taken inside the Louvre (Crow 1985: 1).

In 1737, the exhibitions began being held on odd-numbered years, opening on the Feast Day of St. Louis (August 25) and lasting for three to five weeks. During their run, Salon exhibitions were the dominant public entertainment in the city. The Salon Carré (Square Salon) in the Louvre was filled with paintings from the eye level to the ceiling, creating a feast for the eyes. (figs. 4, 5). Endless waves of spectators filled the room, sometimes making movement inside impossible (Crow 1985: 1).

Salon of 1787, Pietro Antonio Martini, engraving, 1787.

Salon of 1787, Pietro Antonio Martini, engraving, 1787.

Salon Carré at the Louvre, Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Brun, oil on canvas, 24 x 32 cm. circa 1880. Louvre Museum.

Salon Carré at the Louvre, Alexandre Jean-Baptiste Brun, oil on canvas, 24 x 32 cm. circa 1880. Louvre Museum.

From the beginning, Salon exhibitions triggered an immediate and dramatic transformation in the French cultural life. Painters were pressured by the press to address the needs and desires of the public; journalists and critics who demanded this claimed to have public support. State officials stated that their decisions were taken in the public’s interest, and collectors began to prefer paintings that received public approval. In the previous periods, art was displayed in religious rituals and other social spaces and only a minority group composed of artists and their patrons had authority over aesthetics. Now, the tastes and needs of the masses mattered. With the Salons, which were the first platforms for the display of art to be offered in a secular setting, audiences’ aesthetic response became important (Crow 1985: 2-3).

In 1747, an article titled “Reflections on some of the causes of the current state of painting in France[3]”, which was recognized as the first Salon critique, penned by La Fond de Saint-Yenne, was published, (Mayne 1965: ix). However, the first person to offer significant art criticism was the French thinker Denis Diderot (1713-1784), one of the editors of the Encyclopédie, the most ambitious work of the Enlightenment Age[4]. Diderot initiated an approach that would later be adopted by 19th century thinkers, and he was described by literary critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804-1869) as the father of “emotional, enthusiastic and eloquent” criticism (Mayne 1965: ix). Diderot was motivated by ideals such as using science and art to contribute to society’s happiness and to raise a better-educated and virtuous generation (Özsezgin 1996: 7).

For Diderot, art, like science, was another way of searching for the truth. He first wrote for Correspondance Littéraire, whose editorship was passed from Priest Raynal to Baron Grimm[5] in 1754. With his writings, he wanted to inform the prominent figures, intellectuals and elites of Europe about the latest news in art (Özsezgin 1996: 8). The language Diderot used in his critique was encouraging, and it highlighted the positive aspects of artists’ work and sometimes included great praise for certain artists (Özsezgin 1996: 9).

For Diderot, creating and appreciating art is a matter of “passion” and like literature, it matures humans. He thinks of artists as people who are following a higher passion. In his letters, Diderot talks about passion to his lover, Sophie Volland, who contributed to his thinking through their correspondences:

“All my life, I have been an advocate of strong passions. Only strong passions excite and inspire any admiration and fear in me. They give me strength. Passion is what turns talent into art, and without it, art dies. If the degrading nature of humans is not tamed with passion, the result is mediocre and talentless humans, those who live and die like animals. While they are alive, they spend no effort to distinguish higher passions from the rest, and no one remembers them when they are gone. Their names mean nothing to anyone, and no one knows where their graves are, as they are lost in the weeds. (Özsezgin 1996: 9).”

In his Essay on Painting (1796), Diderot defines taste as a convenience acquired by repeated experiences of the mind, a way of reaching what is good and true. This description makes him similar to the thinkers of Antiquity and reflects the spirit of the times he lived in. According to him, an artist is an observer of nature, someone who has a good grasp of what is worth taking from it and combines these features from nature in a coherent way (Özsezgin 1996: 10).

Jean Baptiste Greuze (1725-1802) was one of the painters that Diderot praised the most. On August 15, 1761, an exhibition was held in the Salon Carré in the Louvre, which Diderot calls “the most beautiful salon ever”, featuring two-hundred works of art by fifty-five artists (Diderot 1996: 112). Diderot wrote a long review for Greuze’s “The Village Bride[mh1] ” (fig. 6). After mentioning how hard it was to study the painting because of the large crowds, Diderot praises the Greuze for using all the methods of expression available in academic art (Diderot 1996: 113, Crow 1985: 147):

The Village Bride, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, oil on canvas, 36 x 46,5 cm. Louvre Museum.

The Village Bride, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, oil on canvas, 36 x 46,5 cm. Louvre Museum.

This painting depicts a father who has paid for her daughter’s dowry. It is a moving subject which stirs excitement in the audience. I found the composition really pleasing. We are witnessing a scene that every family is familiar with. There are twelve figures in the painting, all performing their own role, all in their own places. They are lined up in order that makes sense, but it gives you the feeling that a tremor can come and make them all collapse on top of each other. But I Iike the fact, either intentionally or unintentionally, that all these figures found their places in this painting. (Diderot 1996: 113).”

In the Salon of 1763, thirty-nine painters, nine sculptures and eight engraving artists were featured. Diderot wrote a review for this exhibition, which lasted from August 25 to the end of September, and Baron Grimm added some notes which agreed with and softened Diderot’s comments (Diderot 1996: 127). One of the artists featured was Étienne Jeaurat (1699-1789), whose “Favorite Sultana” (fig. 7) we recognize from the Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation’s Orientalist Painting Collection. Diderot compares Jeaurat’s early work to the poetry of Jean-Joseph Vadé, who wrote about the lives and traditions of the lower classes:

Favorite Sultana, Étienne Jeaurat, oil on canvas, 50 x 74.5 cm. 18th century. Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Orientalist Painting Collection.

Favorite Sultana, Étienne Jeaurat, oil on canvas, 50 x 74.5 cm. 18th century. Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Orientalist Painting Collection.

“In the beginning, Jeaurat was the Vadé of art. He painted markets, the Maubert district, kidnapped girls, secret exchanges, shouting old hat merchants, and quarrelling women selling fish. I remember two years ago when he showcased two paintings like these. One was about two young women being taken to Saint-Martin, where one looked sad and the other had cheated on the police superintendent.[mh2] This painting was describing a real-life event (Diderot 1996: 145, 225).”

Diderot also commented on “Lemons of Javotte” (fig. 8), which was exhibited the same year. After stating that this painting did not get much attention, he added:

Lemons of Javotte, Étienne Jeaurat, oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm. 18th century. Special Collection.

Lemons of Javotte, Étienne Jeaurat, oil on canvas, 60 x 80 cm. 18th century. Special Collection.

“My dear friend, Mr. Jeaurat, I leave you to paint whatever you fancy. However, I ask you to show mercy for your gray hair and shaky hands (Diderot 1996: 145).”

Baron Grimm also agrees with Diderot, and after making a comment on Jeaurat’s old age, he states that while the artist was visiting the exhibition he only said it was “promising” about the “Mary’s Marriage”, a painting which was admired by the visitors. Grimm then goes to draw a parallel between Jeaurat and Mercure de France, another art review magazine, calling them both inadequate (Diderot 1996: 146).

In the Salon of 1763, one of the paintings of Antoine de Favray, a painter whom we recognize from the Suna and İnan Kıraç’s Orientalist Painting Collection, was featured (fig. 9). On this painting, which depicted the inside of St John’s Cathedral in Malta, Diderot makes the following comments:

Panorama of Istanbul, Antoine de Favray, oil on canvas, 100 x 213 cm. 1773. Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Orientalist Painting Collection.

Panorama of Istanbul, Antoine de Favray, oil on canvas, 100 x 213 cm. 1773. Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Orientalist Painting Collection.

“If I have to praise, I would praise the artist’s patience. However, if only there was a spark to light up his talent, we would be looking at a completely different painting in front of us now (Diderot 1996: 213).”

Diderot also calls the works of art that gained the artist’s admission to the Academy, which mainly depicted Maltese women, “unfortunate paintings” (Diderot 1996: 213-214).

Even though Diderot believed that the intellectual search for the perceived reality and the observation of nature was the most important aspect of art, it is also evident from his comments on Antoine de Favray’s art and some others that meticulous depictions of details were not sufficient for him. Diderot’s art criticism anticipates the 19th century, which will inherently contain contradicting ideas. In this context, it is no surprise that Diderot also influenced Romantic thinkers. In this context, it is no surprise that Diderot also influenced Romantic thinkers.

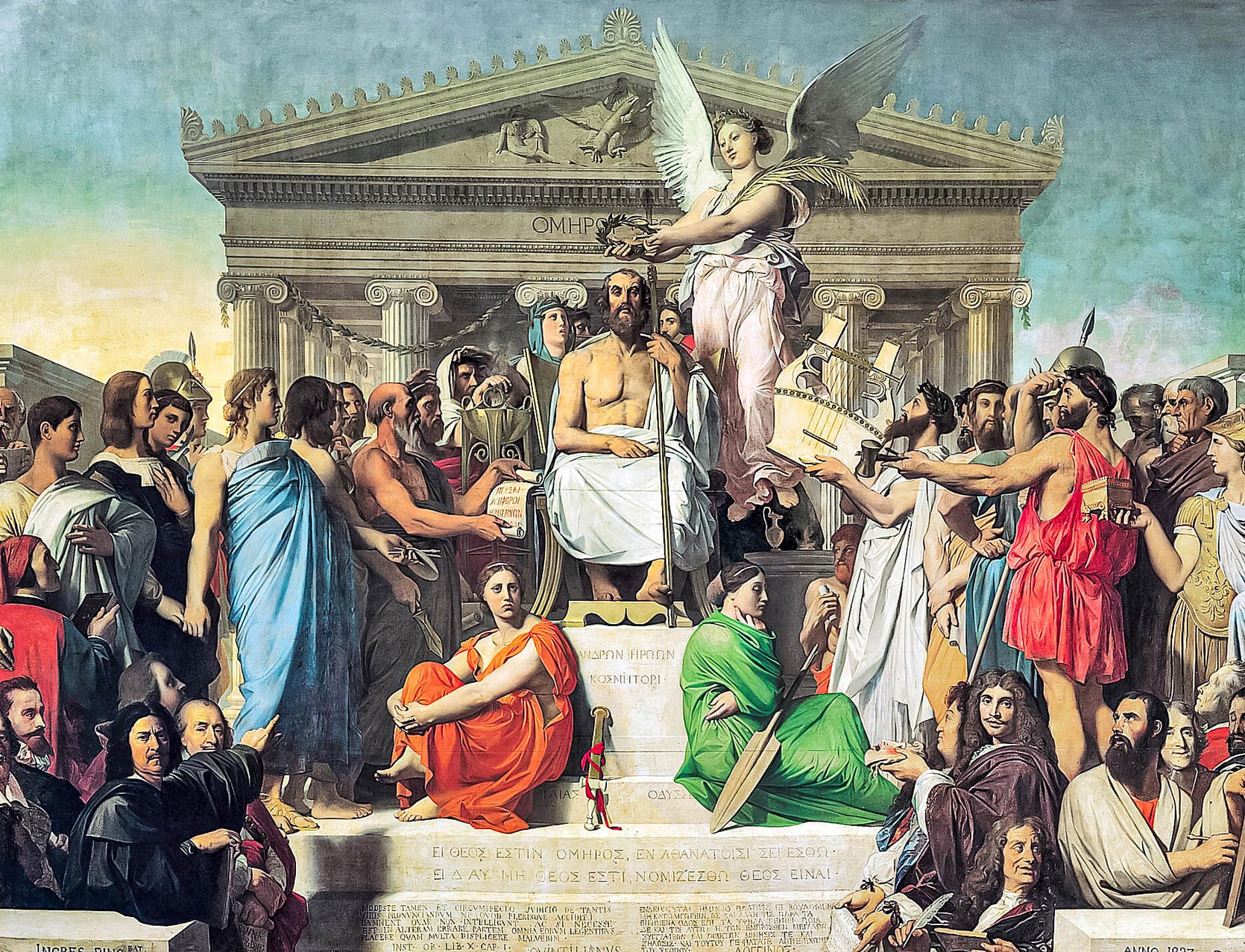

After the French Revolution, the responsibility of organizing the Salon exhibitions passed from the Academy to the École des Beaux-Arts (National School of Fine Arts), and foreign painters were now allowed to exhibit their work here[6]. In 1827, “The Apotheosis of Homer” (fig. 10), painted by Jean-August Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), who was a student of David and a Neoclassic painter, was among the paintings featured in the Salon Carré. His work depicted Classicism as a style that defined physical beauty and perfection, a combination of all the indisputable and enduring rules. He intended to lay a strong cultural infrastructure for the present-day art. The painting where Homer, sitting on the throne like Zeus, is surrounded by artists from different periods, shows how the artistic heritage, starting from the ancient Greek period, continued to the 19th century (Eisenman 2007: 10-11).

The Apotheosis of Homer, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, oil on canvas, 386 x 512 cm. Louvre Museum.

The Apotheosis of Homer, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, oil on canvas, 386 x 512 cm. Louvre Museum.

In his criticism written for the Journal des débats in 1928, Etienne Delécluze (1781-1863) praised Ingres for dispensing originality and accepting formal “archetypes” created by the great artists throughout history:

“Indisputably, great poets, artists and philosophers had individual freedom, but what made them great was the times and conditions they were born into. Homer found himself in an ideal time to create the mythology tradition, Dante to make lyric theology, Shakespeare to bring the ideas of the South to the North, Phidias to personify symbolic ideals and Michelangelo to give form to the Middle Age. Once these grand combinations were formed and established, the only thing left is to constantly reshape these archetypes.”

According to Delécluze, Ingres’s success was hidden in his expertise in reshaping classical archetypes (Eisenman 2007: 11).

The Salon exhibitions and their interpretation also reflected political developments. As a young painter at 21, Théodore Géricault painted “The Charging Chasseur” for the 1812 Salon, completely using his own means (fig. 11). In 1814, when Napoleon lost his empire to the European coalition, the Bourbon dynasty returned to power. The monarchy quickly decided to host a Salon exhibition to highlight the restoration of its cultural structure. Next to “The Charging Chasseur”, Géricault also displayed “The Wounded Cuirassier”(fig. 12), where he depicted a soldier leaving the battlefield. Inevitably, the commentaries on the paintings were all related to the current politics of France and Napoleon’s quick change of fate (Crow 2007: 64-65). The paintings were also criticized for their large size and brushwork resembling a “coarse mosaic”[7].

1. 11. The Charging Chasseur,Théodore Géricault, oil on canvas, 349 x 266 cm. Louvre Museum.

2. The Wounded Cuirassier, Théodore Géricault, oil on canvas, 358 x 294 cm. Louvre Museum.

Another renowned name in the mid-19th century in art criticism was poet, author and translator Charles Pierre Baudelaire (1821-1867). Especially apparent in his early works Diderot was very influential in Baudelaire’s art criticism. When Baudelaire began to write art reviews, some of Diderot’s old articles on the Salon were being reprinted, like his review on the 1759 Salon, which was reprinted in 1844 in l’Artiste magazine. Although 100 years separated Baudelaire’s last review, written for the 1859 Salon, and Baudelaire’s first, written for the 1759 Salon, the similarities between the two thinkers did not go unnoticed by modern critics. For Baudelaire’s 1845 Salon review, Champfleury (1821-1889) commented: “Mr. Baudelaire is as bold as Diderot, without the paradox” (Mayne 1965: ix).

In his review of the 1846 Salon, Baudelaire made the following comments on Romanticism, which he viewed as being the most recent, latest expression of the beautiful: “To say the word Romanticism is to say modern art--that is, intimacy, spirituality, colour, aspiration towards the infinite, expressed by every means available to the arts”. Baudelaire states that romanticism brought him “directly to Delacroix” (1798 - 1863) and praises “Dante and Virgil in Hell”, which was exhibited in the 1822 Salon and considered one of the precursors to Romantic art (fig. 13) (Baudelaire 2004: 96-97). In his article where he also comments on others’ opinions and attitudes towards “Dante and Virgil in Hell”, Baudelaire states “Once the artist began to really prove himself and the good news spread by the day, the Academy, which normally despises everything, had no choice but to take this genius seriously (Baudelaire 2004: 109).”

Dante and Virgil in Hell, Eugène Delacroix, oil on canvas, 189 x 241 cm. Louvre Museum.

Dante and Virgil in Hell, Eugène Delacroix, oil on canvas, 189 x 241 cm. Louvre Museum.

The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1855 signified the end of an era and the beginning of another. Aesthetic taste was now determined by amateurs, who could influence the decisions made by the Academy, the king or the emperor. By the demise of the Second Empire in the 1870s, modern art was flourishing. Now, neither the church, the state, the aristocracy nor the Academy could set the rules. The bourgeois, which wanted acknowledgement of its tastes, was becoming the dominant force in society. The better-off members of the merchants or industry owners without a title now purchased art for investment and decorating. This transformed the preferences in artwork. The shift of economic power from the aristocrats to the bourgeois after the French Revolution was responsible for the shift in aesthetic taste almost a hundred years later. (Mainardi 1989: 33).

The Paris Salons were funded by the Second Empire (1852-1870) and constituted the most important event of the year in contemporary art. The increasing numbers of participants, critics and visitors added more prestige to these events which brought different groups with different interests together. In 1863, there were so many paintings that were refused, a “Salon des Refusés”, or the "exhibition of rejects" had to be established. Still, the Salons were able to incorporate many varieties of art until the 1870s. After the demise of Napoleon III’s reign, the independent exhibitions of the Third Republic took away the prestige of the Salon and divided the critics’ attention. The most notable critics of this period included Baudelaire, Emile Zola (1840 - 1902), Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) and Théophile Thoré (1807 -1869). News and criticism on the exhibitions, written by many different critics, were published in a variety of magazines and newspapers (Parsons and Ward 1986: vii).

Originally shaped by the Salon exhibitions and by art critics into a common mold, aesthetic taste became more diverse as times changed. Modern art emerged thanks to artists that stood against the generally accepted tastes, methods and institutions, as well as to critics that supported or criticized these artists.[8]

R. Barış Kıbrıs

Curator

Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation

Orientalist Paintings Collection

REFERENCES

ARTUN, Ali. “Baudelaire’de Sanatın Özerkleşmesi ve Modernizm,” The Painter of Modern Life, Charles Baudelaire, Ali Berktay (translated), İletişim Yayınları, İstanbul, 2004.

BAUDELAIRE, Charles. “Salon of 1846”, The Painter of Modern Life, Charles Baudelaire, Ali Berktay (translated), İletişim Yayınları, İstanbul, 2004.

CROW, Thomas. “Classicism in Crisis: Gros to Delacroix,” Nineteenth Century Art, A Critical History, Stephen F. Eisenman (ed.), Thames and Hudson, London, 2007.

CROW, Thomas E. Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris, A Critical History, New Haven ve London, 1985.

ÖZSEZGİN, Kaya. “Diderot ve Sanat Eleştirisi”, Denis Diderot, Paris Salon Sergileri 1759, 1761, 1763, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, İstanbul, 1996.

DIDEROT, Denis. “Salon of 1761, Denis Diderot, Salons: 1759, 1761, 1763, Kaya Özsezgin (translated), Yapı Kredi Yayınları, İstanbul, 1996.

EISENMAN, Stephen F. (ed.), Nineteenth Century Art, A Critical History, Thames and Hudson, Londra, 2007.

MAINARDI, Patricia. Art and Politics of the Second Empire, The Universal Expositions of 1855 and 1867, Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1989.

MAYNE, Jonathan (ed.), Art in Paris 1845-1862, Salons and Other Exhibitions Reviewed by Charles Baudelaire,Phaidon Publishers Inc., London 1965.

PARSONS, Christopher and Martha WARD, A Bibliography of Salon Criticism in Second Empire Paris, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986.

[1] <https://www.artistes-francais.com/en/>

[2] Deloynes Collection, Cabinet des Estampes, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, no. 3, p. 28-9.

[3] Réflexions sur quelques causes de l'état présent de la peinture en France.

[4] Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts).

[5] Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm (1723 - 1807): German journalist, art critic and encyclopedist.

[6] <https://www.artic.edu/library/discover-our-collections/research-guides/paris-salons-1673present>

[7] <https://sites.google.com/a/plu.edu/paris-salon-exhibitions-1667-1880/salon-de-1814>

[8] See Art in Theory, 1815- 1900, An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Charles Harrison, Paul Wood, Jason Gaiger (ed.) Blackwell Publising, United Kingdom, 2008.

Ali Sami is born in Rusçuk in 1866, and moves to İstanbul. Because his family is registered in the Beylerbeyi quarter of Üsküdar, Ali Sami is also called Üsküdarlı Ali Sami. He graduates from the Mühendishane-i Berri-i Hümayun in 1866 and becomes a teacher of painting and photography at the school.

A firm believer in the idea that a collection needs to be upheld at least by four generations and comparing this continuity to a relay race, Nahit Kabakcı began creating the Huma Kabakcı Collection from the 1980s onwards. Today, the collection can be considered one of the most important and outstanding examples among the rare, consciously created, and long-lasting ones of its kind in Turkey.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)