25 November 2020

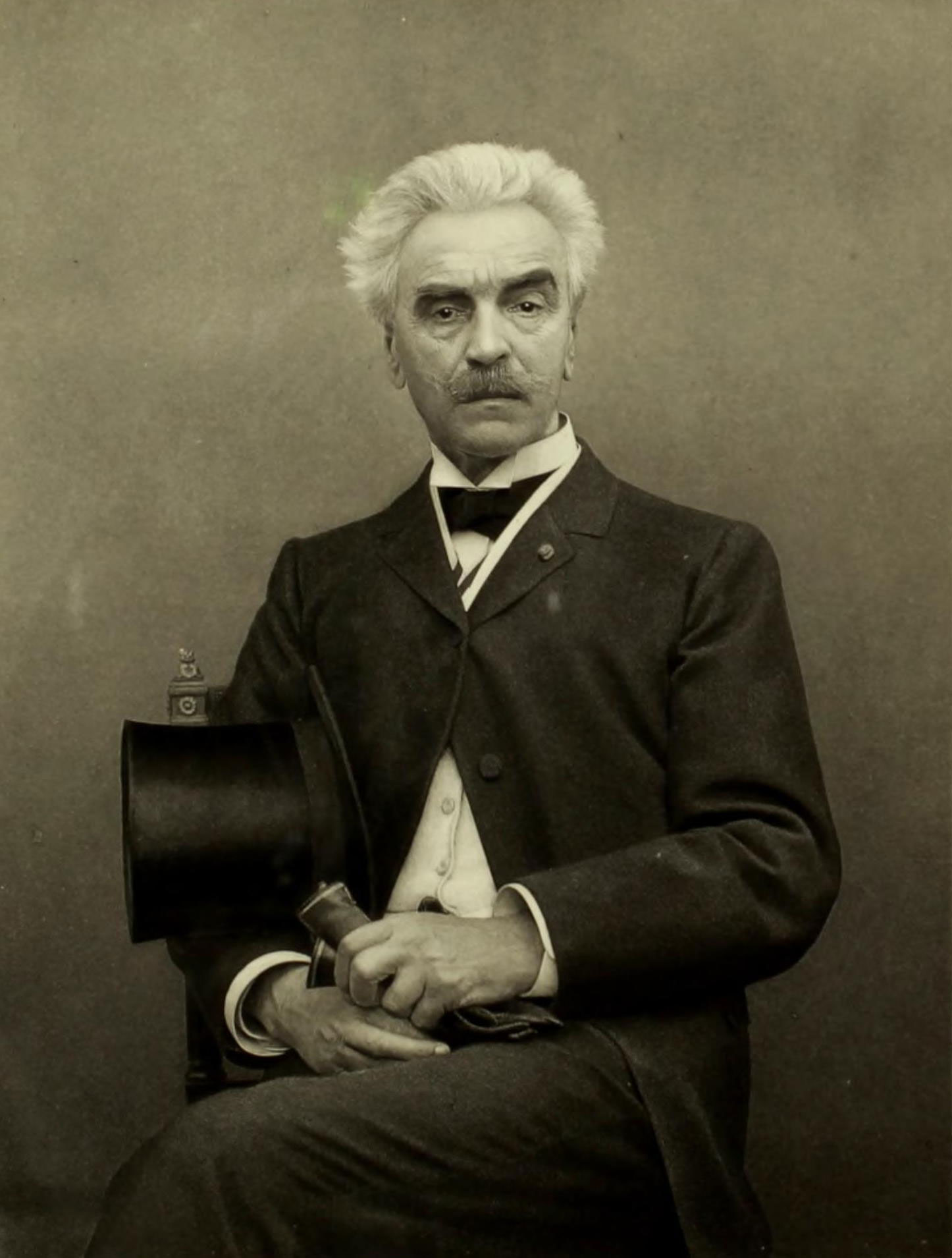

Photogravure portrait of Jean-Léon Gérôme printed by Goupil, ca. 1892.

Photogravure portrait of Jean-Léon Gérôme printed by Goupil, ca. 1892.

Jean-Léon Gérôme is among the most renowned artists of the second half of the 19th century. One of the most fervent advocates of academic painting, Gérôme declared a personal war against modern movements such as Impressionism. In the final periods of his life, and with the ascent of the movements he opposed, he did perhaps lose his former popularity, but was not forgotten in the 20th century like many other academic painters. The most important reason for this was the fact that his works, marketed through the Goupil Gallery, had already taken their prominent place in the leading painting collections of the world, and mostly in collections in the United States (image 1).

Gérôme is one of the first names that comes to mind today regarding Orientalist art. As a general discourse and artistic language that developed parallel to the colonialism of the industrializing Western World in the 19th century, Gérôme created some of the most debated visual works of Orientalism, which stood out with its aim of redefining its own identity, determining cultural opposites and expressing prohibited fantasies. Thus, it comes as no surprise that Gérôme’s painting titled “The Snake Charmer” was used on the cover of “Orientalism”, Edward Said’s renowned book dated 1978 that analyses and criticizes this specifically Western cultural phenomenon (Roberts 2015:75). In addition to these features, Gérôme also occupies an important place in the history of Turkish painting. Our leading painters that influenced the art climate of the 19th century were either Gérôme’s students, or were influenced by his art.

A star is born

Gérôme was born in 1824 in the town of Vesoul in the Haute-Saône region, and passed away in 1904 at the age of seventy-nine. The young Gérôme grew up in a bourgeois family environment during the French Third Republic and received a traditional education, which included Greek, Latin and drawing classes (Germaner 2014:120). Gérôme moved to Paris in 1840 and began his art training at the studio of Paul Delaroche, and in 1843 joined his master’s tour of Italy, which included Florence, Rome, the Vatican and Pompeii. In 1844, on his return to Paris, he studied for a period at the Charles Gleyre (1806-1874) studio and registered at Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the School of Fine Arts in 1846.

Gleyre’s students Gérôme, Gustave Boulanger (1821-1874) and Henri-Pierre Picou (1824-1895) had formed a group known as the Néo-Grecs. Their subject matter was inspired by antiquity, however, instead of Neoclassicism’s more serious subject matter, the artists focused on everyday life. Since they were also influenced by the new discoveries at Pompeii, they were also referred to as the Néo-Pompéiens (Germaner 2014:120). In 1847, Gérôme received a third-class medal at the Paris Salon with his painting titled “The Cock Fight” (image 2) which reflects his Néo-Grec approach. Renowned art critic Théophile Gauthier’s review of this work was the first step towards his increasing fame (<https://www.musee-orsay.fr/>).

The Cock Fight, oil on canvas, 143 x 204 cm. 1846, Musée d’Orsay.

The Cock Fight, oil on canvas, 143 x 204 cm. 1846, Musée d’Orsay.

The artist was awarded with a second-class medal for the works titled “The Virgin, the Infant Jesus and Saint John” and “Anacreon, Bacchus and Eros” which he exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1848, and in the following years he began to receive significant commissions from the French Government. In 1852, he received a commission from the government of Napoleon III to produce a large mural with the subject “The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ” (image 3) which is today at the Musée de Picardie (<https://www.musee-orsay.fr/>). In this work, Napoleon III was identified as a new Augustus (

The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ, oil on canvas, 6,20 x 10,15 m. 1855, Musée de Picardie.

The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ, oil on canvas, 6,20 x 10,15 m. 1855, Musée de Picardie.

Turning towards East

The artist first came to Istanbul in the year 1853 with actor Edmond Got. In 1854 he travelled the shores of Greece, Turkey and the Danube (Rosenthal 1982: 77). He took part in the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1855 with five works, including his painting titled “The Age of Augustus, the Birth of Christ”. In 1856, he began his first trip to Egypt and visited Cairo. In 1863 and 1864, he carried out a trip including Syria, Palestine and Egypt (Germaner 2014:120).

The artist had entered a new period in terms of his choice of subject following his trips to the East, and he began to produce paintings with an Orientalist theme. His paintings were full of strong light-and-shadow contrast created by a bright sky, vivid colours, and human figures of different ethnicities and cultures in their unique attire (Germaner 2014:120). The artist began to teach at the Paris School of Fine Arts and in 1865 was elected a member of the Institut de France. In the winter of 1868, he visited Alexandria and Cairo, made drawings and took photographs of mosques to be used in his paintings. In 1869, he travelled to Egypt once again as a guest of Khedive Ismail Pasha for the opening of the Suez Canal, and stayed for three months in Cairo and Northern Egypt (Germaner 2014:120). After visits to Turkey in 1871, 1875 and 1879, Gérôme again went to Egypt in 1874 and 1880. He also travelled to Italy and Spain. The sketches, photographs and visual notes he brought back from all these travels would provide the source material for his Orientalist paintings that would become highly popular. He used the visual material about Eastern Architecture that he gathered during his travels mostly for the composition of spaces in his paintings, and completed these spaces with figures he painted using models that posed at his studio in Paris.

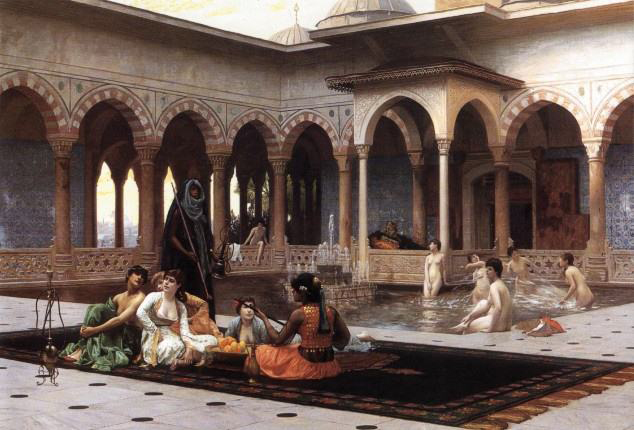

The Terrace of the Seraglio, oil on canvas, 81,9 x 122 cm. 1886, Private Collection.

The Terrace of the Seraglio, oil on canvas, 81,9 x 122 cm. 1886, Private Collection.

The Grand Bath of Bursa, oil on canvas, 70 x 100,5 cm. 1885, Private Collection.

The Grand Bath of Bursa, oil on canvas, 70 x 100,5 cm. 1885, Private Collection.

His visits in 1875 and 1879 to Istanbul led to the painting of works that would be favourites at the Salon exhibitions. Among them were “The Harem in the Kiosk”, “The Terrace of the Seraglio” (image 4), “Snake Charmer” (image 6), based on the Abdullah Frères’s Topkapı Palace photographs (<https://www.clarkart.edu/>). Gérôme also visited Bursa during his trips to Turkey, and especially the baths of the city were used in most of the bath scenes in his Orientalist paintings (image 5) (Germaner 2014:120). In time, the artist’s Orientalist paintings in an academic style became his most preferred works, and took their place among the most appreciated works at the Salon exhibitions, which found great favour among collectors for three decades.

An important visit and relations with Turkey

Gérôme’s trip to Turkey in 1875 was particularly crucial in terms of establishing connections with influential individuals in the field of culture and arts, consolidation of ties with existing acquaintances and thus the potential to find access to a new art market, and also discovering new visual sources. During the course of this process, his former students would act as mediators and facilitators. Gérôme arrived in Istanbul on 15 May 1875. The cosmopolitan art circles of the city were aware of the painter’s fame in France and the United States. Following the artist’s arrival in the city, three different articles about him were published in the Levant Herald newspaper. The first was an introductory piece, published fourteen days after his arrival, announcing his presence to readers. An article published six days later stated that Sultan Abdulaziz had commissioned a number of paintings for the Dolmabahçe and Çırağan palaces from the painter. A third article published four days later stated that his friend and former student Stanislaw Chlebowski had hosted the renowned artists at his home and acted as a guide for him during his tour of Istanbul. As a letter by Chlebowski reveals, it was no other than the Polish palace painter himself who had written these articles (Roberts 2015: 77). The artist was also accompanied by a young French painter named Antoine Buttura during this trip. In a letter, Chlebowski writes that on the second day of this visit he took the two painters on a tour of Istanbul, that they carried out formal visits, probably to receive the necessary permissions and that they would be ready to begin their painting work in the city’s streets in a few days (Roberts 2015:78).

The same letters inform us that, a few days later, they left home at five in the morning to paint, and returned at six in the evening “tired like a dog”. Former students of Gérôme assisted him in meeting individuals in key state positions wherever he went. During this visit in 1875, he came together with artist Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910), and also met with statesman and intellectual Ahmed Vefik Paşa (1823-1891), who founded the Ottoman Theatre, and the French painter Pierre Désiré Guillemet (1827-1878) who had initially come to Istanbul to paint a portrait of Sultan Abdulaziz and then opened an art school in Pera and settled in the city. Ahmed Vefik Paşa, who would later become the governor of Bursa, was in charge of the restoration of Ottoman monuments in this city. During this visit, Gérôme also saw Bursa and produced sketches featuring the important monuments of the city. He would include many monumental structures of Bursa in paintings he would paint, including Yeşil Cami [the Green Mosque] and Yeşil Türbe [the Green Tomb] (Roberts 2015: 79).

Among important figures Gérôme was in contact with were also the palace photographers of the Sultan Abdulaziz era, Abdullah Frères. The artist had had his portrait taken at their studio in Pera during his visit in 1875, and the photographs taken by the three Armenian brothers were among the primary visual sources of the artist’s paintings. An article published in the Levant Herald on 9 November 1877 states that Gérôme sent his painting titled “Bull and Picador” with a note that it was presented as a memento to the Abdullah Frères, a Buttura landscape and certain photogravures of Gérôme and Fortuny to the brothers. In a letter sent to Gérôme five days later, Abdullah Frères write that they are prepared to send the painter any other photographs he may need. These photographs, which included certain parts of the Topkapı Palace that were closed to photographers and painters other than the palace photographers, were no doubt of incalculable value as visual sources for Gérôme (Roberts 2015: 79).

The Snake Charmer, oil on canvas, 82,2 × 121 cm. ca. 1879, The Clark Art Institute.

The Snake Charmer, oil on canvas, 82,2 × 121 cm. ca. 1879, The Clark Art Institute.

For instance, in order to paint the tiles that form the background of the famous “The Snake Charmer” (image 6), Gérôme used photographs of two different parts of the palace, the Golden Road and the Baghdad Kiosk, taken by Abdullah Frères (Roberts 2015: 76).

His role in the formation of the Ottoman palace collection

Gérôme was married to Marie, the daughter of Adolphe Gouphil, the owner of Goupil art Gallery (Kaya 2006: 75). The fact that he was the son-in-law of the most renowned art dealer of the period enabled his works to enter the most important collections across the world. One such collection was the art collection of the Ottoman Palace, which was formed after Tanzimat, the Reorganization. The person in charge of developing the collection with new purchases made during the reign of Sultan Abdulaziz, was none other than Ahmet Ali Bey, also known as Şeker Ahmet Paşa, a student of Gérôme and Boulanger at the Paris School of Fine Arts. The exhibition of paintings held in 1875 by Ahmet Ali Bey, the organizer of the first art exhibitions in Turkey, had also attracted the attention of Sultan Abdulaziz, who appointed him as an aide responsible of developing his art collection (Kaya 2006: 74).

Works of artists supported by the Goupil Art Gallery and admired by the art market of the period would be added to the palace collection if they also received the appreciation of Sultan Abdulaziz and his aide, Ahmet Ali. Sultan Abdulaziz, who is known to have made drawings himself, was knowledgeable about art enough to advise his painter Chlebowski, and was the first Ottoman sovereign to organize a visit abroad and attended the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1867, played the most significant role in the selection of the works for the palace collection. On the other hand, it was inevitable that, mostly, the works of artists who worked with the Goupil Gallery were purchased. Gérôme himself was among the primary actors in both leading the correspondence and the selection of works (Kaya 2006: 79). In a letter dated 19 October 1875, Gérôme wrote “I personally have inspected the style and quality of the works sent to you” to state his contribution to this selection (Roberts: 81).

Among works purchased, the works of the painters of the Barbizon School, which had hugely influenced Ahmet Ali Bey as a painter, too, held a significant place. The collection also included leading figures of French Academic painting, including Gérôme, Gustave Boulanger and William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905). From Gérôme’s works included in the palace collection, “Lion in the Den [Lying Lion]” and “Bashibazouks [Zeibeks]” (image 7) were also sent to and exhibited at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1878 (Germaner 2014: 119; Kaya 2006: 74).

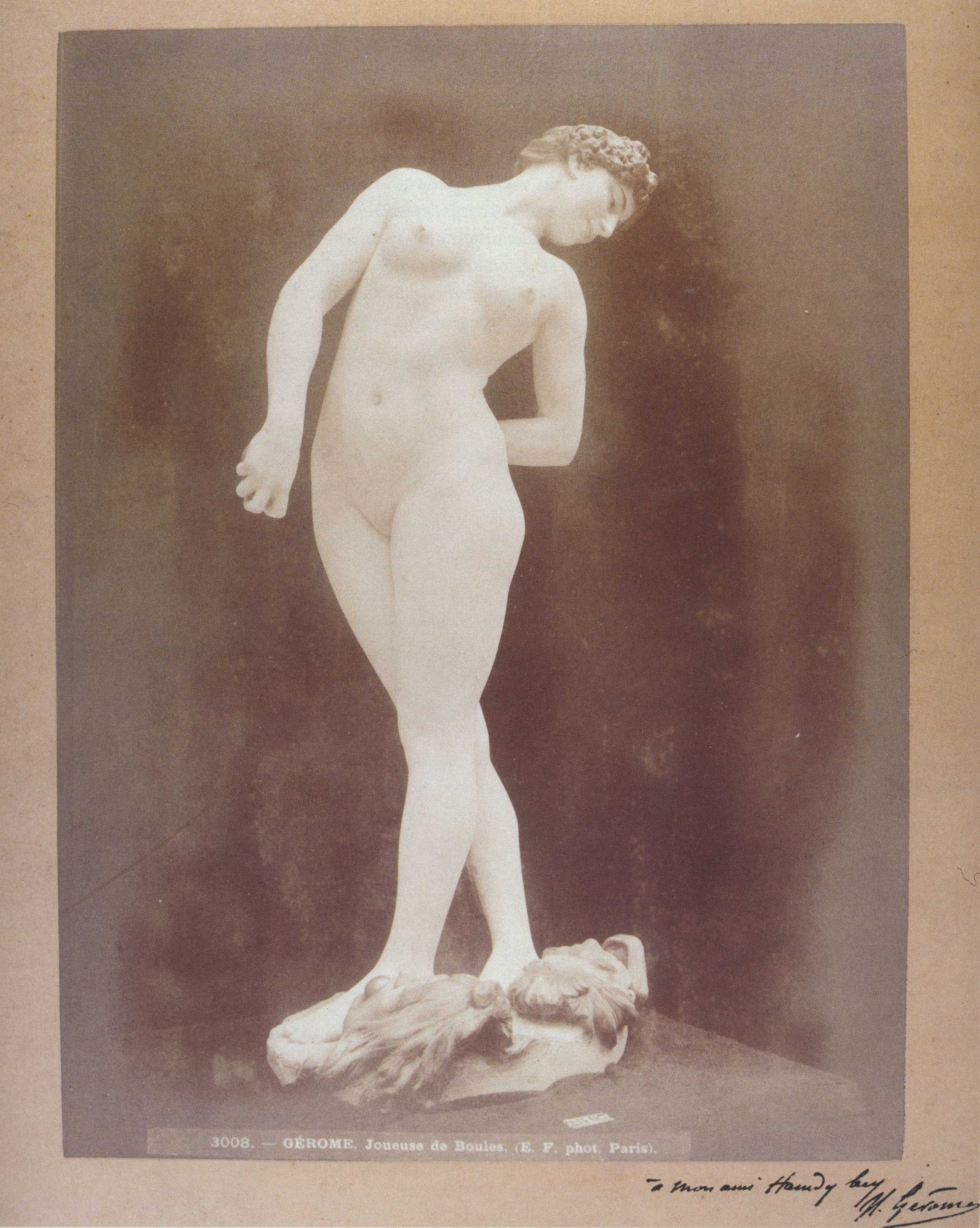

Photograph of Gérôme’s sculpture titled “XXX” (1901) at the Musée Georges-Garret in Vesoul dedicated with the inscription “To my friend Hamdi Bey”, Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum Archive.

Photograph of Gérôme’s sculpture titled “XXX” (1901) at the Musée Georges-Garret in Vesoul dedicated with the inscription “To my friend Hamdi Bey”, Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum Archive.

Osman Hamdi Bey and Gérôme

The personal connections to provide the visual sources that formed the basis of his work as a painter, to market his works or to acquire the necessary permissions played a highly significant role in Gérôme’s career. Former students like Ahmet Ali Bey and Chlebowski were individuals who provided such connections and opened doors. Many sources state that Osman Hamdi Bey, too, was a student of Gérôme at the Paris School of Fine Arts. However, school records show that Osman Hamdi did not study at the Paris School of Fine Arts. Catalogues of exhibitions in Paris that he took part in record him as a “student of Boulanger”. The fact that Osman Hamdi does not mention Gérôme as a teacher in the Paris Salon Exhibitions where he would have had to formally introduce himself provides unequivocal evidence that he was not his student. It is also known, on the basis of their correspondence that continued for many years that the two artists were well-acquainted. It is probable that this acquaintance was first established during Osman Hamdi’s student years in Paris (Eldem 2010: 246-248). On the other hand, it could also be considered that the misunderstanding that Osman Hamdi was a student of Gérôme, already repeated during Osman Hamdi’s lifetime, was based in certain stylistic similarities in the two artists’ works. Osman Hamdi’s paintings, made to be sent to exhibitions abroad, and featuring figures placed in spaces woven with details of traditional Ottoman architecture, reflecting the meticulous craft of French academic painting is perhaps the most significant reason of this ascription.

From a letter Gérôme wrote to Osman Hamdi on 12 January 1875, we learn that Hamdi Bey invited the French painter to stay at his home when he visited Istanbul in spring. However, since Gérôme had already promised his student Chlebowski, he had to reject this offer. Following this visit by Gérôme, the relationship between the two artists developed from a relatively formal acquaintance to a friendship where views on art were shared, and both artists recommended each other students travelling from Paris to Istanbul or Istanbul to Paris (Eldem 2010: 247).

Gérôme developed an interest in multicoloured sculpture, and in a letter he wrote on the topic on 23 January 1891 to Osman Hamdi Bey, then the director of the Imperial Museum, the French artist expressed his fascination with the colours used in the Sarcophagi of Sidon. From another letter by the French artist, we learn that Osman Hamdi provided earth pigments from Berlin so that Gérôme could produce permanent paint. Gérôme was in deep disagreement with his colleagues regarding the use of colour in sculpture, thus he wanted to know what colours were used in the Alexander Sarcophagus and saw this as proof of the veracity of his approach (image 8) (Eldem 2010: 247)

Photograph of Gérôme’s sculpture titled “XXX” (1901) at the Musée Georges-Garret in Vesoul dedicated with the inscription “To my friend Hamdi Bey”, Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum Archive.

Photograph of Gérôme’s sculpture titled “XXX” (1901) at the Musée Georges-Garret in Vesoul dedicated with the inscription “To my friend Hamdi Bey”, Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum Archive.

The legacy of an artist

When we examine Jean-Léon Gérôme’s approach both to sculpture and to painting, we see that his main references are Neo-Classicism, based on classical antiquity or ideas on art from antiquity, and a successor of its style, the Néo-Grec. He lived in a period when artistic taste was rapidly changing, and he vehemently opposed new movements, first and foremost Impressionism. His works fell from favour when the modern movements of the 20th century radically transformed taste, however today, -along with the debates about their Orientalist perspective- his works have retaken their place at the top of the artistic agenda, .

Selected Bibliography

ACKERMAN, Gerald M. The Life and Work of Jean-Léon Gérôme, Sotheby’s, London, 1986.

ELDEM, Edhem. Osman Hamdi Bey Sözlüğü [An Osman Hamdi Bey Dictionary], Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, İstanbul, 2010.

GERMANER, Semra. “Jean-Léon Gérôme”, Presidential Art Collection, Ömer Faruk Şerifoğlu ed., Presidential Publications, Ankara, 2014, 120-121.

KAYA Gülsen Sevinç. “Dolmabahçe Sarayıİçin Goupil Galerisi’nden Alınan Resimler / The Paintings Purchased from Goupil’s Art Gallery for the Dolmabahçe Palace”, Osmanlı Sarayı’nda Oryantalistler / Orientalists at the Ottoman Palace, Ömer Taşdelen ve İlona Baytar eds., Milli Saraylar Daire Başkanlığı, Istanbul, 2006, 71-91.

LAFONT-COUTURIER, Hélène. Gérôme & Goupil: Art et Entreprise, Réunion des Musées Nationaux, Paris, 2000.

ROBERTS, Mary. Istanbul Exchanges: Ottomans, Orientalists, and Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture, Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2015.

ROSENTHAL, Donald A. Orientalism, the Near East in French Painting, 1800–1880, Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Rochester N.Y., 1982.

A firm believer in the idea that a collection needs to be upheld at least by four generations and comparing this continuity to a relay race, Nahit Kabakcı began creating the Huma Kabakcı Collection from the 1980s onwards. Today, the collection can be considered one of the most important and outstanding examples among the rare, consciously created, and long-lasting ones of its kind in Turkey.

Pera Museum, in collaboration with Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV), is one of the main venues for this year’s 15th Istanbul Biennial from 16 September to 12 November 2017. Through the biennial, we will be sharing detailed information about the artists and the artworks.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)