26 October 2020

Mario Prassinos’s Atelier, Eygalieres, Provence 1973, Photo by: Alain Desvergnes, Centre d’Archives

Mario Prassinos’s Atelier, Eygalieres, Provence 1973, Photo by: Alain Desvergnes, Centre d’Archives

Who is Mario Prassinos? Mario From Pera

Mario Prassinos liked Istanbul more than the current Istanbulites of today. It is obvious that you can understand this from the article written by her daughter Catherine Prassinos in the Pera Museum's book on the artist:

“We used to look at a huge, heavy album full of family photos with my dad. He had dedicated the first part of the album to Turkey. My father used to tell me about Istanbul and the exile. I feel that that the exile is a part of me as well, and by talking about him, he conveys the seagull cries on the Bosphorus, the Turkish language and the Sultanahmet Mosque to me. It gave him great pain that he had to abandon Turkey, his home and his friends. "

Mario Prassinos was born in Istanbul. In detail, he was born in Pera in 1916 as a child of a Greek family of artısts. The house where he was born is still here and standing. Unfortunately, Mario and his family were exiled in 1922 and settled in France. But he would never forget his Istanbul. If you take a closer look at his works, you can understand that his soul could not be fully anchored in France, where he lived until the age of 69, and that he always missed Istanbul.

The Raven and Others

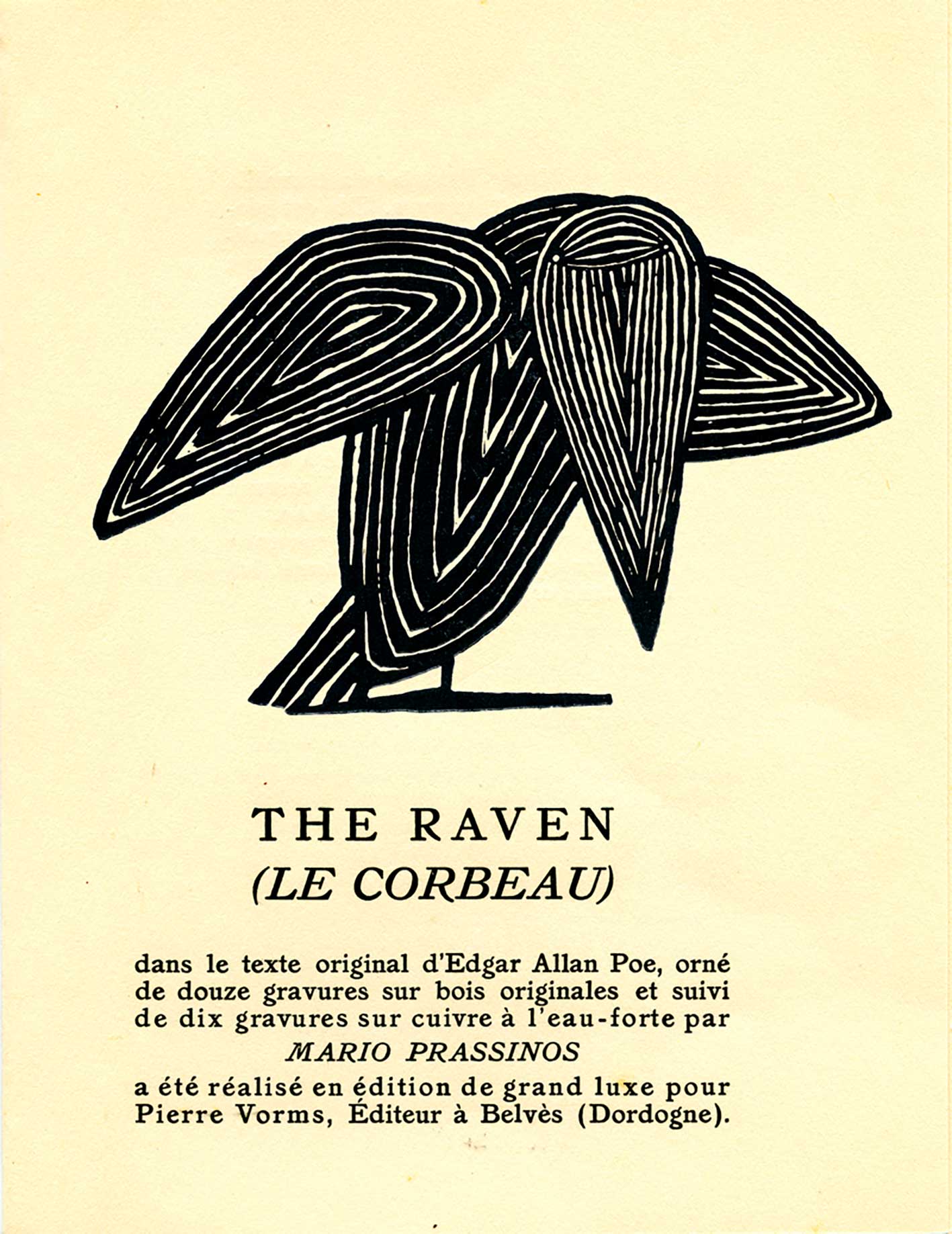

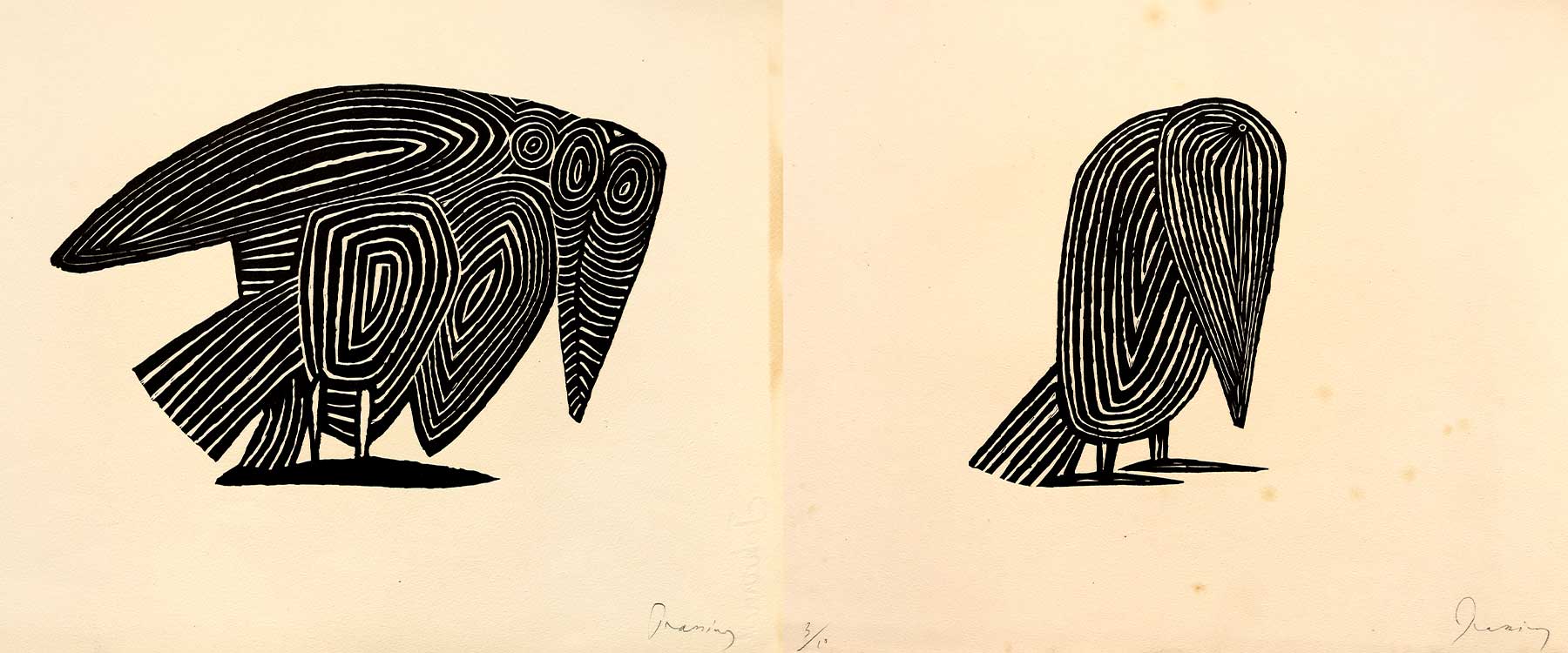

Prassinos, who had been illustrating especially in surrealist publications since 1934, also prepared the book covers of the L'âge d'or (Golden Age) collection under the editorship of Henri Parisot in the 1940s. In the same period, he designed 205 cover models, each more striking than the other, for the La Nouvelle Revue Française (NRF) collection released by Gallimard Publishing House. Who was in this collection? Apollinaire, de Beauvoir, Breton, Camus, Faulkner, Hemingway, Kafka, Rimbaud, Sartre… The illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe for his 1952 book The Raven are undoubtedly the most interesting of all his designs.

The Raven, Edgar Allan Poe, 1952, Editions Pierre, Vorms, 19 x 14,5 cm, Centre d’Archives, Mario Prassinos

The Raven, 1952, Wood print, Centre d’Archives, Mario Prassinos, 28 x 36 cm

Turkish Rose, 1966

Turkish Rose, 1966

Wool, low warp carpet

Private Collection

120 x 80 cm

Turkish Rose

When they moved to villa Seurat in Paris in 1941, among Mario Prassinos' neighbors was Jean Lurçat, known for his weaving work. Lurçat was going to introduce Prassinos to woolen threads after a while.

To weave, patterns were first drawn on paper, then the code numbers on the color chart of the yarns were written on paper based on a kind of preview that happens only in the mind of the designer for the moment. For someone like Prassinos who used his memory well, weaving was like a new game. Sometimes calligraphic expressions appeared in his weavings, sometimes repeating the patterns he used in his other works, sometimes revealing images evoking the past through the names he gave such as Turquerie and Turkish Rose.

Turquerie, 1967, Wool, low warp carpet 212 x 266 cm

Turquerie, 1967, Wool, low warp carpet 212 x 266 cm

Portraits: In Search of Lost Memories

Portraits held a special place in Mario Prassinos' career, who saw his memory as the source of his creativity. Prassinos used to say that to paint someone, he does not aim at physical resemblance, but needs memories of that person formed in his mind. While studying Bessie Smith, whom he had never met, with an original approach, he first learned everything he could about this jazz artist and created a Bessie image for himself and then reflected this image on the canvas.

Bessie’s Grave, 1963

Bessie’s Grave, 1963

Oil on canvas

145 x 113 cm

Prassinos' grandfather Prétextat Lecomte, on the other hand, was a colorful character who became friends with intellectuals such as Alexandre Vallaury, Şeker Ahmet and Osman Hamdi, known for his art writings in newspapers as well as his painting and mosaic works in the cosmopolitan Pera of the period. For Prassinos, it was primarily a figure that he portrayed as a child in the decor of their home in Istanbul.

Lysandre Prassinos, who was interested in painting and photography while working as a literature teacher, would only admit years later that he portrayed his father as a power, an ancestor figure, on his canvas, although the revolutionary stance of the Greek folk language and his necessity to live in exile affected Prassinos.

Tattooed Hill

In 1951 Mario Prassinos settled with his wife Yollande in Eygalières, south of Avignon. That still model he encountered every morning when he left the house; this self-tattooed hill captivated Prassinos. The struggle that the painter went through while doing his hill studies included both an inner speech and a questioning for Prassinos. Ultimately, the striking “Little Alps” series, which gained a calligraphic expression in places with the painter's brush soaked in ink, emerged.

“I made that blind, that deaf, that dumb speak. I covered it with images. With each passing year our relationship has become closer. Every confusion turned into a battleground between his obsessive performance and my desire to give him life. Those fractures, those bushes that grew over the years, those tears that grew slightly deeper were all spots and currents, ink and paper, the hill turned into my enormous pattern. It became mine."

Mario’s Trees

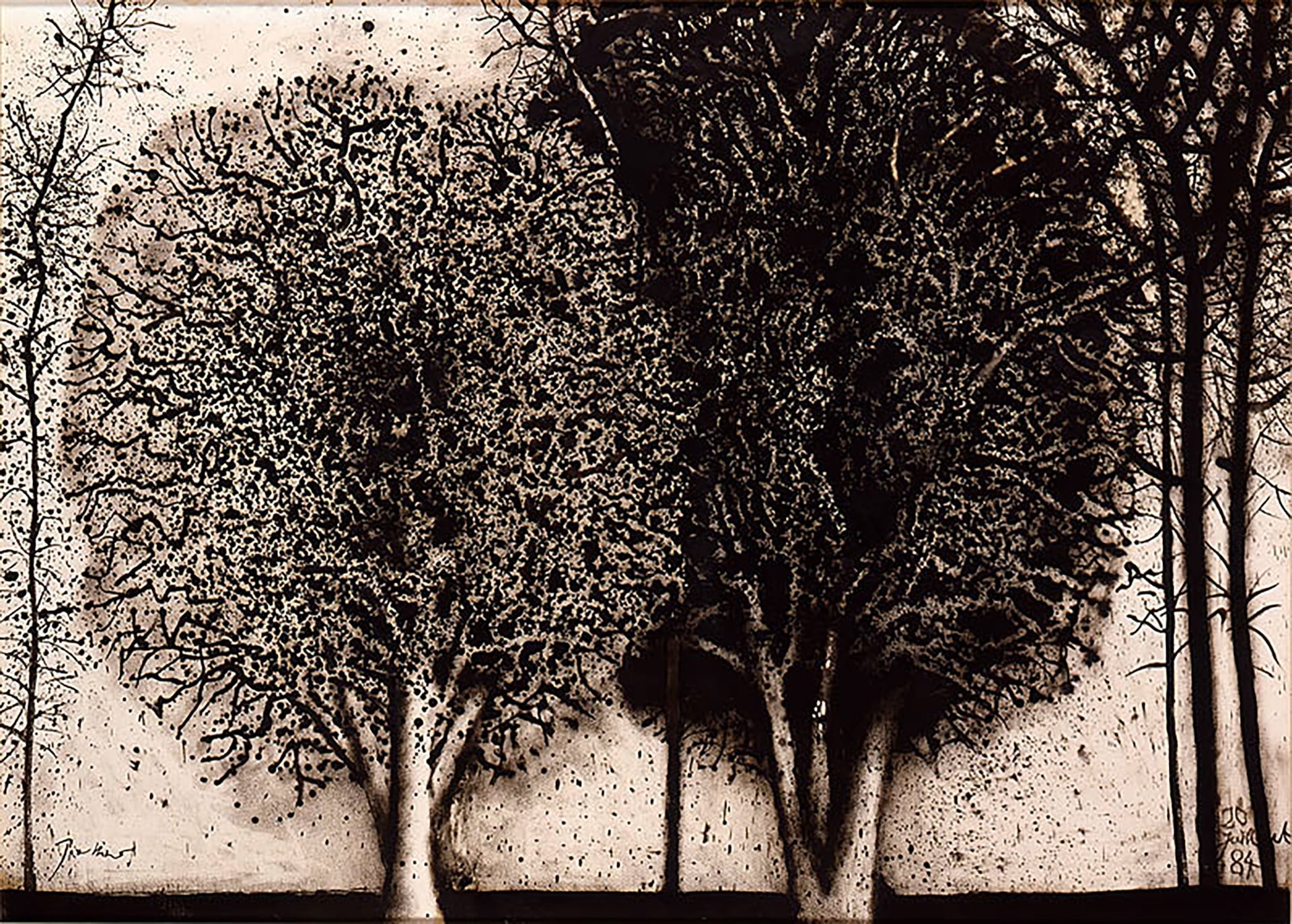

Cypresses, trees and Turkish landscapes are among the most interesting themes in Prassinos' art. For Prassinos, the cypress groves in Üsküdar or the trees in Petits Champs, which he saw every time he went to the terrace of their house in Istanbul, must have been strong images from childhood. Trees, which contained a strong meaning together with their roots that grasp the soil, suggested their own existence with a similar metaphor in the imagination of the painter.

Turkish Landscapes, Little Moon, 1981, Oil on canvas, 130 x 162, 5 cm

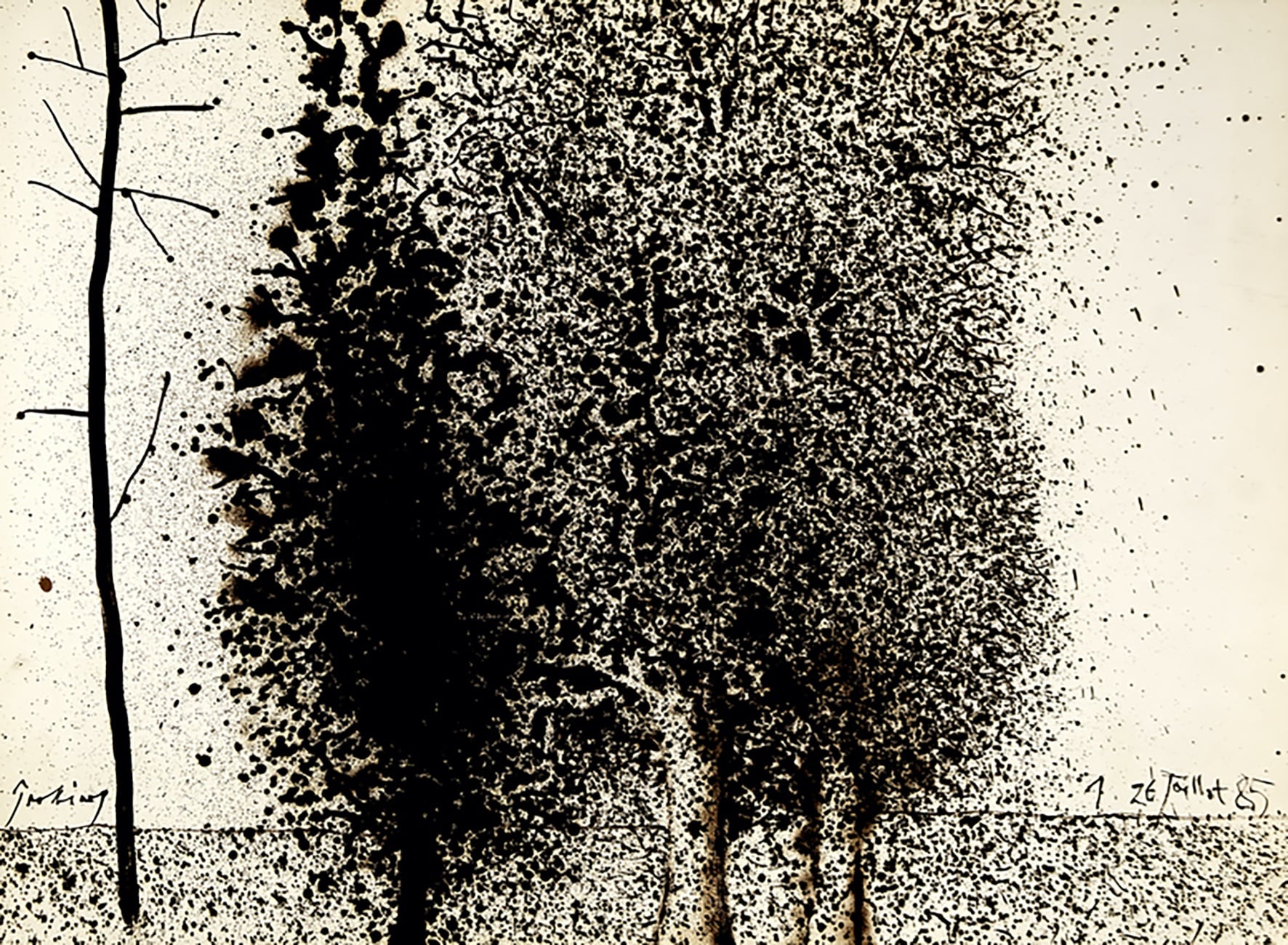

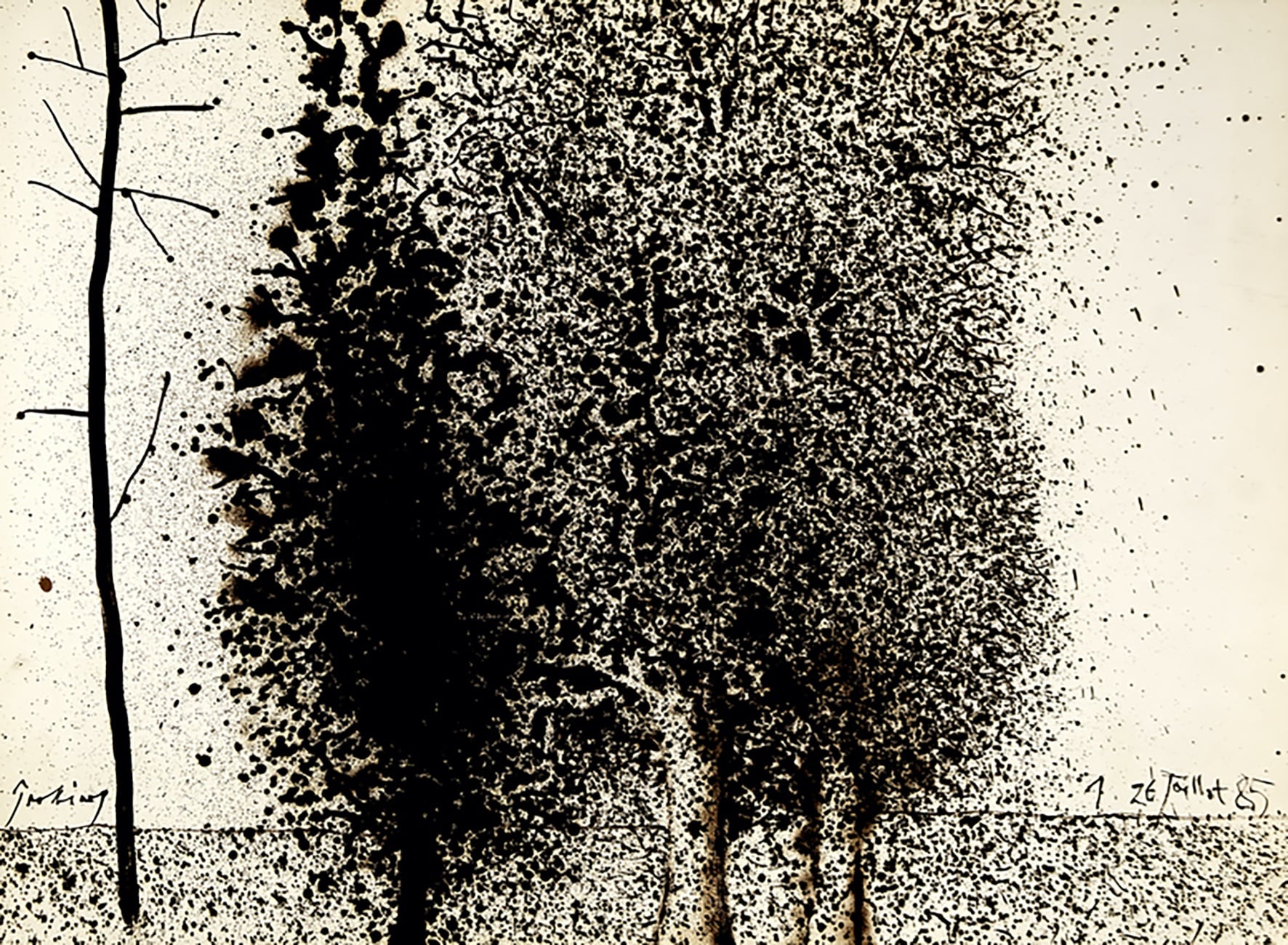

The trees in the "Paintings of Pain" series are important in that they are the compositions he prepared to realize that he has come to the end of his life. Sketches seen here are from St. Although it belongs to the paintings inside the Notre Dame de Pitié Chapel in Rémy de Provence, it is Prassinos' latest works. In the sketch of three trees leaning against each other, with no leaves, with thorns, as if drying, the painter seems to indicate to the viewer a life that will be reborn in the soil where life ends.

Study for Paintings of Torment, 26 July 1985, Oil on paper, Private Collection, 57 x 76 cm

Trees, 20 July 1984, Oil on Arches parchment paper affixed to the canvas, 75,4 x 105,8 cm

Study for Paintings of Torment, 28 July 1985-3, Oil on paper, Private Collection, 57 x 76 cm

Mario Prassinos died in France in 1985.

Among the most interesting themes in the oeuvre of Prassinos are cypresses, trees, and Turkish landscapes. The cypress woods in Üsküdar he saw every time he stepped out on the terrace of their house in İstanbul or the trees in Petits Champs must have been strong images of childhood for Prassinos.

Three people sleeping side by side. On the uncomfortable seats of the stuffy airplane in the air. Three friends. I’m the friend in the window seat. The other two are a couple, Emre and Melisa. I’m alone, they are together. And another difference. I’ve only closed my eyes. They are asleep.

I remembered a game as I was waiting in the passenger lounge for the ferry to arrive just a few minutes ago. A game we used to play at home when I was young, in my country that is very far away from here, a relic from the distant past; I don’t even remember how we used to play it. The kind of game that makes me feel a thousand times lonelier than I already am among the crowd waiting to get on the ferry.

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 200 TL

Discounted: 100 TL

Groups: 150 TL (minimum 10 people)