07 June 2024

In his book exploring the cultural history of souvenirs, Rolf Potts discusses how such objects assume meaning through personal stories: Objects turn into memories with the stories they hold. “When we collect souvenirs, we do so not to evaluate the world, but to narrate the self.”1 The relationship with collected objects also changes over time. The object can carry one to a certain moment; oftentimes it freezes and preserves that moment. As we grow further away from that moment, the possibility of feeling the past and lost time and the personal history recalled by that object renders it more valuable. As poet and critic Susan Stewart writes, “The souvenir is not simply an object appearing out of context, an object from the past incongruously surviving in the present; rather, its function is to envelop the present within the past.”2

According to Arjun Appadurai, who investigates how cultural exchange and social relations are shaped through objects, “beneath the seeming infinitude of human wants, and the apparent multiplicity of material forms, there in fact lie complex, but specific, social and political mechanisms that regulate taste, trade, and desire.”3 The connotations one ascribes to objects are determined by personal relations. These relationships might also change how objects are used and how they are put into circulation by being transmitted from one place to another. As Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi wrote, “Our addiction to materialism is in large part due to the paradoxical need to transform the precariousness of consciousness into the solidity of things. The body is not large, beautiful, and permanent enough to satisfy our sense of self. We need objects to magnify our power, enhance our beauty, and extend our memory into the future.”4

Personal relations forged with objects lay the ground for the creation of a collection. A collection that grows through relationships developed with similar objects over time both carries clues about the person com- piling the collection and enriches the social meanings of the given objects. “The deep-rooted power of collected objects stems neither from their uniqueness nor from their historical distinctiveness,” said Jean Baudrillard. “It is not because of such considerations that the temporality of collecting is not real time but, rather, because the organization of the collection itself replaces time. And no doubt this is the collection’s fundamental function: the resolving of real time into a systematic dimension.”5 From this perspective, it could be argued that the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Collections present a selection that reflects the founders’ personal areas of interest and the stories of these objects, reading time according to how they were collected. Meanwhile, the museum is a space where the memory objects of collections are exhibited and where these objects meet the public. When these ceramics produced in Kütahya and used in everyday life constitute a collection, the collector’s personal relationship with them assumes a public value. According to Maurice Rheims, the desire to collect is a game of passion. “A further phenomenon accompanying collectors’ mania is the lack of awareness of the present… They become detached from contemporary life to exist in a dreamlife of the past.”6 Perhaps the passion of a yearning mental journey to the past may assume different connotations when opened to the public.

Michel Foucault tackles the relationship of museums with time through the concept of heterotopia. “Heterotopias of time” such as museums enclose in one place objects from all times and styles. They exist in time but also outside of it because they are built and preserved to be physically insusceptible to time’s ravages. “By contrast, the idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort of general archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, all epochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place of all times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, this whole idea belongs to our modernity. The museum and the library are heterotopias that are proper to western culture of the nineteenth century.”7 While reflecting on the memories of objects, one should not disregard what the collections and museums hosting these items add to the memories.

In this part of the exhibition, the artist duo Skuja Braden materializes the memories of a day spent in the museum with the installation Time Stream (2023). Taking photographs of the works in the museum with their phones, including the Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics Exhibition, the duo transfers these images onto ceramics, rendering them timeless. The images lost among the countless digital visuals that are often never looked at again defy the accelerated flow of time when they assume the ceramic form. The everlasting quality of ceramics that survive from prehistory to the present paves the way for us to reconsider the dynamic relationship we forge with time. As memories from the past transform into future memories, the river in the back- ground elicits the relentless flow of time. As water lily leaves flow through the river of time with the telephone screens they carry, they suggest that digital tools such as phones might also someday disappear. Could the memory of objects be more reliable than the memory of digital tools?

In his installation Those Born to Earth (2023), Metehan Törer traces the knowledge and memory transmitted among generations through ceramics. Inspired by the 1950s double-handled vase in the Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics Collection, his work consists of vases resembling the body in various forms stretched on the floor with monumental chandeliers placed around them. The reliefs of fish scales on the chandeliers once again draw inspiration from the vase ornaments in the collection. Törer, who layers the ceramic surface rather than patterning it, uses the broken carnation motif as one of the installation’s central elements. This object, which also finds its place in the collection, is thought to represent the transient world or spiritual love. Transmitting his own experiences to objects, the artist produces ceramic figures using an autobiographic narrative language. Those Born to Earth, which recalls a ritual space comprised of figures chained to one another, reanimates the memory of the queer body with ceramic objects.

Livia Marin's artistic practice explores our relationship patterns with everyday objects in this day and age when goods are in wide circulation. The Remnants I (2018) series brings together the leftover pieces of broken ceramic objects on a two-dimensional plane. Setting forth from the question of what could be done with the objects of disrupted forms that have lost their functions, Marin focuses on remnants of broken pieces. She explores the common grounds of existence of the broken and the remnants or the possibilities of representing an object that does not exist or has been lost. The gold leaf used in the background makes reference to kintsugi. This traditional Japanese technique entails the repair of broken ceramic objects with a mixture of gold and varnish. Breaking and repairing is regarded as a part of the history and memory of the given object in kintsugi, and there is no attempt to hide it. Remnants I is a nostalgic homage to the objects we lose, break, damage, spoil, or can no longer reach in our personal collections.

Voronoi (2020), produced by the artist collective oddviz, inspired by the Suna and İnan Kıraç Foundation Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics Collection, transmits to the present a selection of about 150 works from between the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries using the photogrammetry technique for three-dimensional modeling and digitalization. Focusing on the points of transitivity and interaction between the physical and the digital, the video offers a brand-new perspective on the preservation and conservation of cultural heritage, their transmission to future generations, and the role of the museum within this process. The video draws its title from the mathematical function that allows for the breaking up of modeled objects in the digital medium. Shown previously in the museum’s Coffee Break exhibition, Voronoi offers a wider-scale experience in scope of the current exhibition.

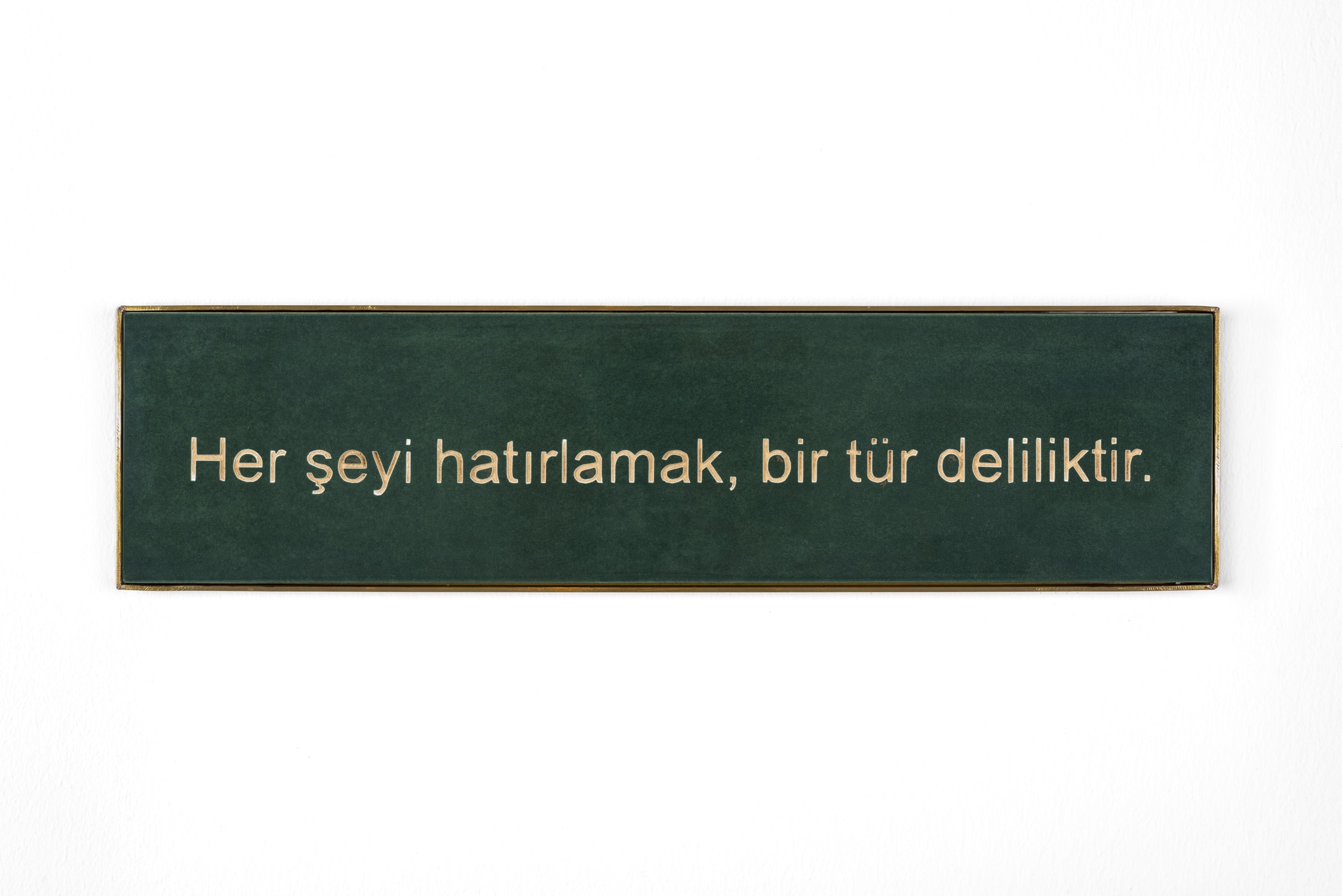

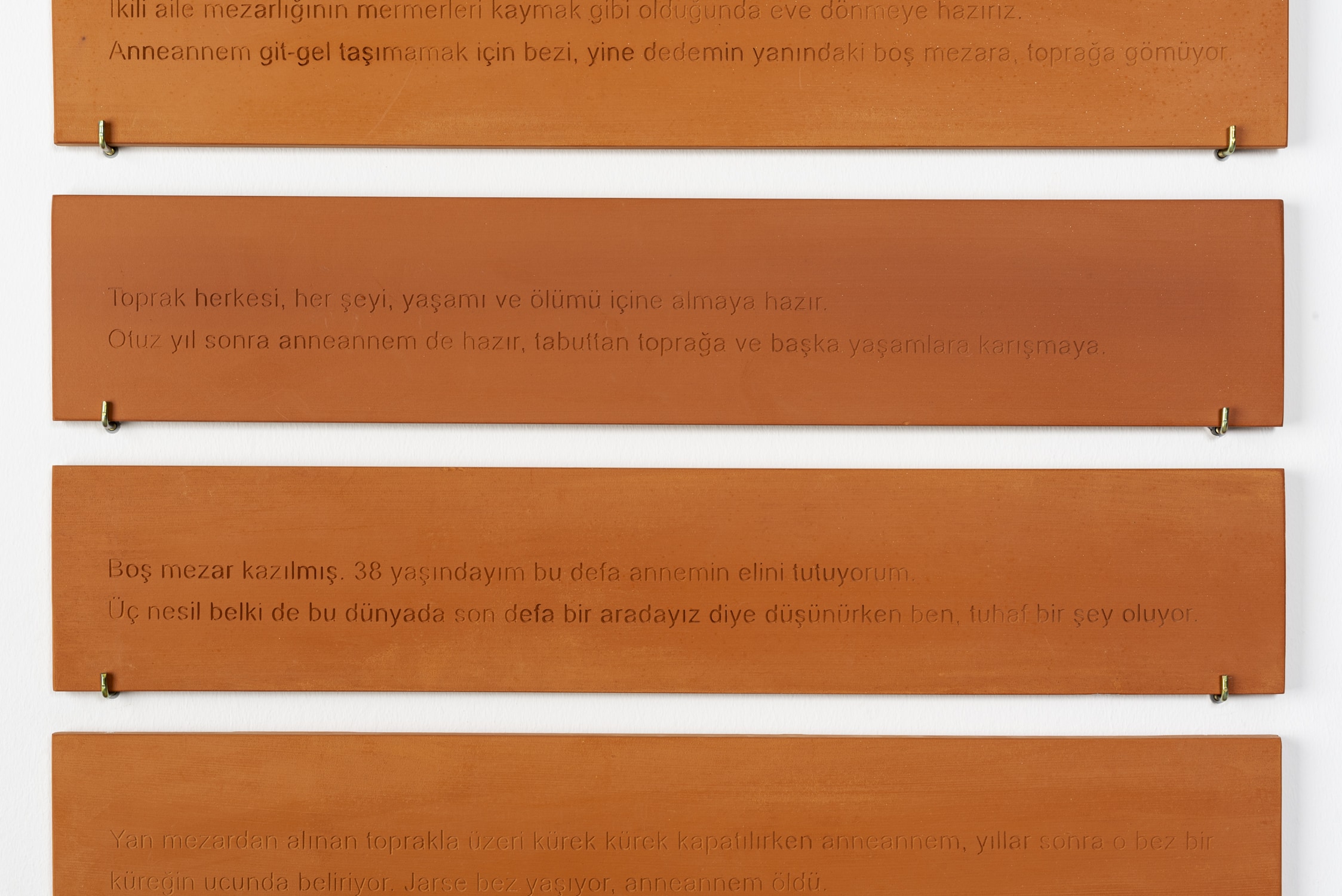

In her installation produced for the exhibition titled Tablet (2023), Yasemin Özcan centers the relationship of women from three different generations with soil. Working primarily with ceramics and text in recent years, the artist explores the potential of objects to create and recall memories focusing on the essence of the material, that, in this case is the soil. The installation, which is a part of the Remembering everything is a form of madness series that the artist began in 2016, borrowing its name from Brian Friel’s play, focuses on the memory of objects and what is remembered through them.

1. Rolf Potts, Souvenir (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2018).

2. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 151.

3. Arjun Appadurai, ed.The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986).

4. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, “Why We Need Things”, History From Things: Essays on Material Culture, eds. Steven Lubar andDavid Kingery (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993, 20-29).

5. Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects, transl. James Benedict (London: Verso, 1996), 95.

6. Maurice Rheims, The Strange Life of Objects, transl. David Pryce-Jones (New York: Atheneum, 1961), 34.

7. Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” Architecture Mouvement Continuité, transl. Jay Miskowiec (October 1984).

Excerpted from curator Ulya Soley's article in the exhibition catalogue Souvenirs of the Future.

Explore! all the details about the exhibition sections:

Souvenirs of the Future

Reminiscences of the Motifs

Memory of the Region

Remembering the Future

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)