07 June 2024

Objects also bear the memory of the geography to which they relate. Ceramics, with soil as their primary material, are directly linked to the land where they are produced: forging a direct relationship with earth, ceramics bear the memory of the soil where they come from. The abundant kaolin in Kütahya’s soil, which makes it favorable to ceramics production, has led to the development of various techniques and the establishment of ceramics studios in the city. Each type of soil offers different color possibilities for ceramics, resulting in shades unique to the region. As a material fired in high temperatures, ceramics endure the destructive effects of time, with some dating back twenty-five thousand years. This defiance of time reminds us once again of importance of establishing a relationship with soil while focusing on memories left for the future.

Memories and souvenirs assume value through their connection with their origin. For the tourist who is inclined to bring home an object from where they have traveled or who collects certain items to present to someone who has not accompanied them on the journey, anything that evokes that place can be valuable. And yet “the relationship between souvenir and place has become abstracted in the 21st century.”1 As travel becomes easier, the intercontinental journeys of objects also multiply. Presently, it is not too difficult to pro- cure an object unique to a place without ever going there. This might weaken the object-memory relationship, but souvenirs still function as a status symbol and as evidence of time spent in a visited place. In his book The Tourist, Dean MacCannell makes the following comparison between geography and objects: “While sights and attractions are collected by entire societies, souvenirs are collected by individual tourists.”2 The memory of the region signifies a space that brings together personal and societal memories.

Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s site-specific installation Both Roots and Stems, Both Are Both Not (2023), produced for the exhibition, is inspired by the mangrove trees that grow on the shores of tropical regions. Just like these trees, whose roots stretch down into the earth, traditional modes of production and memories surface through the installation. These entangled roots, which also evoke Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s rhizome model, based upon diversity, multiplicity, and nonhierarchical relationships as an alternative to the hierarchical tree model of Western philosophy, allow for the consideration of different time frames simultaneously. Inspired by the forms of Kınık, Phrygia, and Hittite and the traditional Kınık pouring technique, the ceramic cups were shaped in Kınık Village. This near-forgotten pottery tradition was introduced to the region by Bulgarian immigrants. The ceramic cups form a web, with branches rooting from the wall. These ceramics, branching out to the museum walls, storage areas, archives, and exhibition space, establish a continuity between the building, the works, and the past and present. The entangled roots on the surface render visible the memory of the region.

Jorge Otero-Pailos' artistic practice employs experimental conservation techniques that offer a critical approach to cultural heritage. The artist produces works focusing on history and memory at the intersection of architecture and art. Commissioned for this exhibition, the Souvenir of the Pera Museum transforms the dust accumulated in the building into a kaleidoscopic tile pattern. Photographing the dust collected from the museum’s façade using a microscope, Otero-Pailos produced a work of traditional wall tiles in which he transferred the design created with repetitions of these images. While proposing a progressive approach to dust, which is customarily cleaned and eliminated as it accumulates, this installation applied to the museum wall weaves the memory of the building with the memory of the region.

The porcelains in Candice Lin’s installation A Hard White Body, A Porous Slip (2017) evoke objects found in a shipwreck in the future. James Baldwin’s novel Giovanni’s Room, in which the protagonist falls in love with a man he meets at a bar when he is about to marry a woman, is combined through objects and video with the story of botanical scientist Jeanne Baret, who embarks on the first overseas journey in the eighteenth century while disguised as a man. What the two characters have in common is their struggle against the racial, gender, and class norms imposed upon them. The artist “works with porcelain, invoking the history of exot- icism, virology and global trade, and raising the question of a racialized language: porcelain, this hard white body, a Chinese object of Western desire inimitable until the mid-eighteenth century.”10Porcelain evokes purity, whiteness, and insusceptibility to cracks and stains. Infecting the porcelain installation with urine and the distillation of medicinal plants, the artist stages the meeting processes of organic and inorganic materials. Working mostly with clay, Lin’s artistic practice has evolved into installations using both the material and conceptual qualities of ceramic.

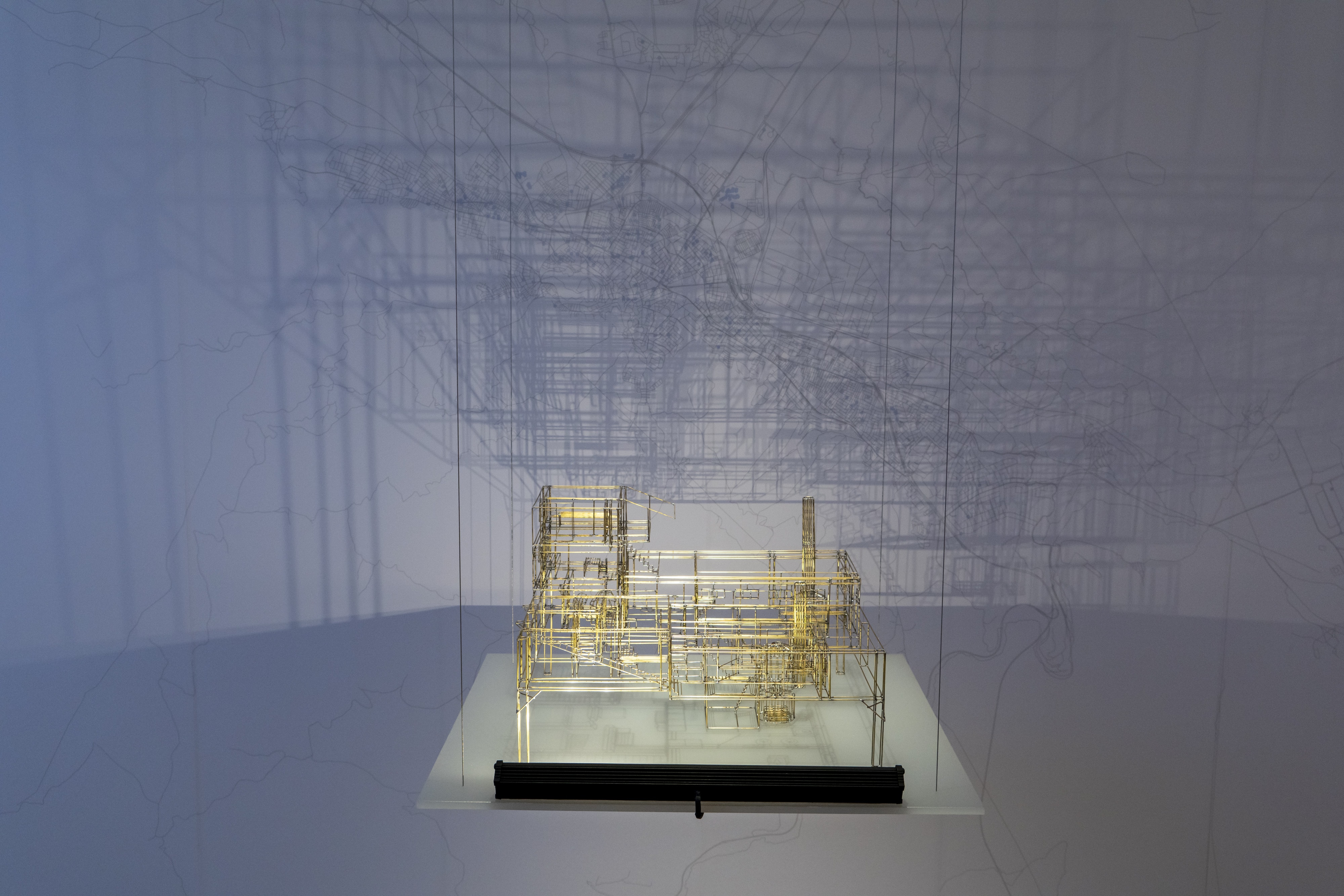

Artist Bilal Yılmaz and curator Lydia Chatziiakovou, in the scope of their joint project Creative- Craft Platform, create regional maps of craft workshops to highlight the potential of crafts in the contemporary context. Focusing on the workshops in Kütahya, they drafted a report tracing the current state of ceramics workshops, producers, and associations in the region. The map serves as a guide for the locations of the work- shops and producers in the report. Yılmaz focuses on the story of the Elhamra Workshop that was built in 1959 in the model he built for the exhibition. Elhamra is a special workshop that has remained intact, allowing one to discover the history of çini production, its relationship with the city, its socio-economic ties and the living conditions of various periods. As the only remaining workshop that used to produce ceramics from raw material to final product using a traditional pit furnace, Elhamra transforms into a learning center where traditional craft techniques are transmitted from generation to generation, keeping the memory of the region alive. Photographs and documents related to its past are displayed in the collection gallery, thus this place, which houses the history of ceramics in Kütahya, provides a rich context for the museum collection.

1. Rolf Potts, Souvenir (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2018).

2. Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure 8 Class (New York: Schocken Books, 1976), 42.

3. Lotte Arndt ve Lucas Morin, “Candice Lin, A Hard White Body,” Bétonsalon Centre for Contemporary Art and Research sergi metninden.

Excerpted from curator Ulya Soley's article in the exhibition catalogue Souvenirs of the Future.

Explore! all the details about the exhibition sections:

Souvenirs of the Future

Reminiscences of the Motifs

Memory of Objects

Remembering the Future

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)