07 June 2024

Prominent motifs from Islamic art continue to shape contemporary productions with their symbolic connotations. The plant ornaments and geometric patterns seen in Kütahya tiles are used in ceramic objects such as vases and jugs as well as in architectural ornaments. As artisanship became a part of artistic practices with the blurring of art and craft, the use of traditional motifs has also flourished. In this context, how are these motifs currently structured or designed beyond their traditional connotations? This part of the exhibit presents works in three different mediums inspired by the ceramic tiles on the walls of a church, a mosque, and a palace. At the same time, this section tackles nature with its contemporary connotations as the source of plant ornaments.

Adriana Varejão’s work, titled Carpet-Style Tilework on Canvases (1999), is an installation comprising forty-five canvases of different shapes and sizes piled on the floor and against the wall. The canvases that look like a flat surface at first glance are oil paintings of tiles with cobalt blue and white flower motifs. This work layering the surface of the painting depicts the traditional azulejo tiles of Our Lady of Joy Church, built in the seventeenth century, which corresponds to the three centuries when Brazil was a colony of Portugal.

Meanwhile, Exploratory Laparotomy II (1996) combines irezumi patterns from Japanese tattoo culture with Portuguese ceramic motifs on white tiles. The body transforms into a map, while broken ceramics and patterns overlap on this fictional operating table. “Exploratory laparotomy” refers to the surgical opening of the abdominal cavity for diagnostic purposes. It is possible to see traces of the artistic movement Anthropophagia, which emerged in Brazil in the 1960s, in this work by Varejão. The movement’s name, referring to cannibalism, alludes to the role of cultural cannibalism in Brazil’s liberation from colonization and makes reference to the tribal rituals in the country’s history. The clean appearance of the tiles, laid out methodically, is disrupted by the pieces recalling internal organs and blood stains.

In her installation Route Saz Yolu (2023), produced for the exhibition, Burçak Bingöl places a ceramic panel from Topkapı Palace at the center. This panel painted by Şahkulu, who was the head miniaturist of Topkapı Palace in the sixteenth century, is a garden landscape that captivates viewers with its rich details. Saz yolu refers to the style Şahkulu represents. The flower buds, hatai flowers, dagger leaves, pheasants, and mythological animals like ch’ilin are presented as tiles on the panel painted in cobalt blue. Bingöl, who divides the panel into pieces cartographically and purges its background to depict the motifs, thus emphasizing its details, follows the traces of the saz yolu style on the Silk Road. She situates this panel from Topkapı Palace as a stop on a trade route spanning from China to Europe and a portal opening to this road in history. Route Saz Yolu, which she envisions as a research sketch, reveals the artist’s thought patterns.

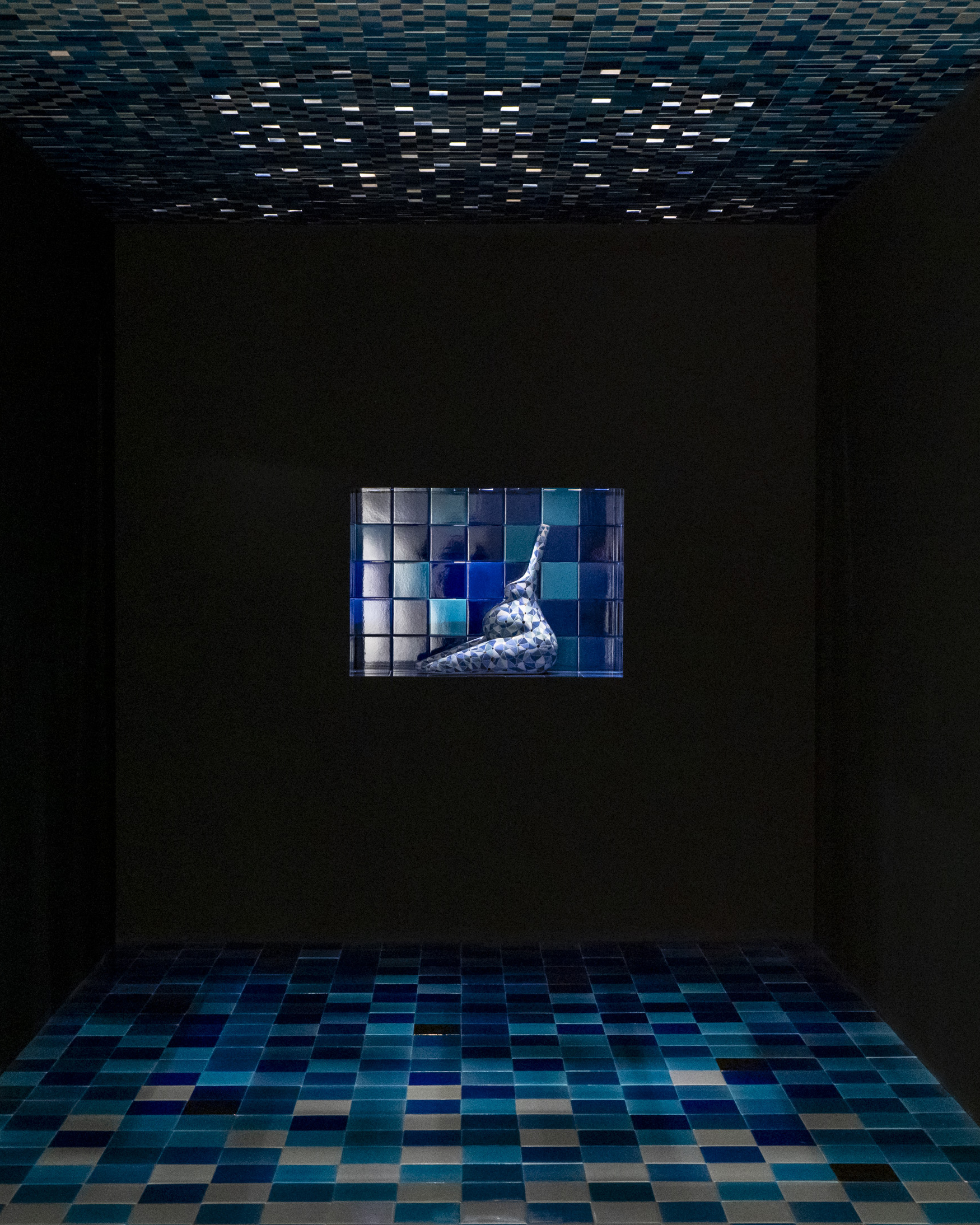

In her site-specific installation Double Niche (2023), Elif Uras explores motifs and forms that reference prehistory with a contemporary approach. The mosaics laid out on the floor and ceiling are inspired by the “hand on the waist” motif thought to represent abundance and fertility and likened to the female form used widely in kilim and tapestries in Anatolia. The division of this geometric motif into ceramic pieces renders its pixels visible with reference to digital visual language. Uras interprets the repeating geometric rim designs in Kütahya ceramics by transforming them into the geometric form that most resembles the human figure. The light beams emanating from the ceiling recall domed Ottoman buildings like mosques and bathhouses. Meanwhile, an alcove in the room hosts a sculpture titled Goddess of the Moon, inspired by the statues of women from the paleolithic era found in Çatalhöyük, depicted sitting down and headless with thin necks and accentuated breasts and curves. The cave mouths and niche forms painted in this period are interpreted as symbols of holiness or worship spaces. The installation presents a rich realm of references spanning from prehistorical sculptures and murals to kilim and ceramic ornaments.

Francesco Simeti’s installation Petting Wilderness (2023) sets forth from the idea of nature as memory. The collage, in which the artist combines nature images from databases like Shutterstock with motifs from the museum’s Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics Collection, is a brightly colored, sterile, plastic representation of nature. What problems may arise from these representations, where plants and animals transform into drawings or digital images? From a human-centered standpoint, nature can quickly evolve into a commercial tool. With each day, economic gain and exploitation, along with the destructive effects of tourism, nature is transformed into a concept that exists merely in memory. Through the collage, the artist offers a critical approach to the curbing of collective imagination through visual databases, in which the more popular images circulate further and propagate existing misconceptions.

The collage, exhibited as a curtain, is accompanied by ceramic sculptures that turn into recollections of nature inspired once again by objects depicting plant and animal forms from the collection.

In his painting Wall (2018), Taner Ceylan depicts in detail a dilapidated wall in the courtyard of Rüstem Paşa Mosque, built by Mimar Sinan in the sixteenth century. The wall in the outer courtyard of this mosque, which the artist has often visited since his youth, becomes the subject matter of this painting.

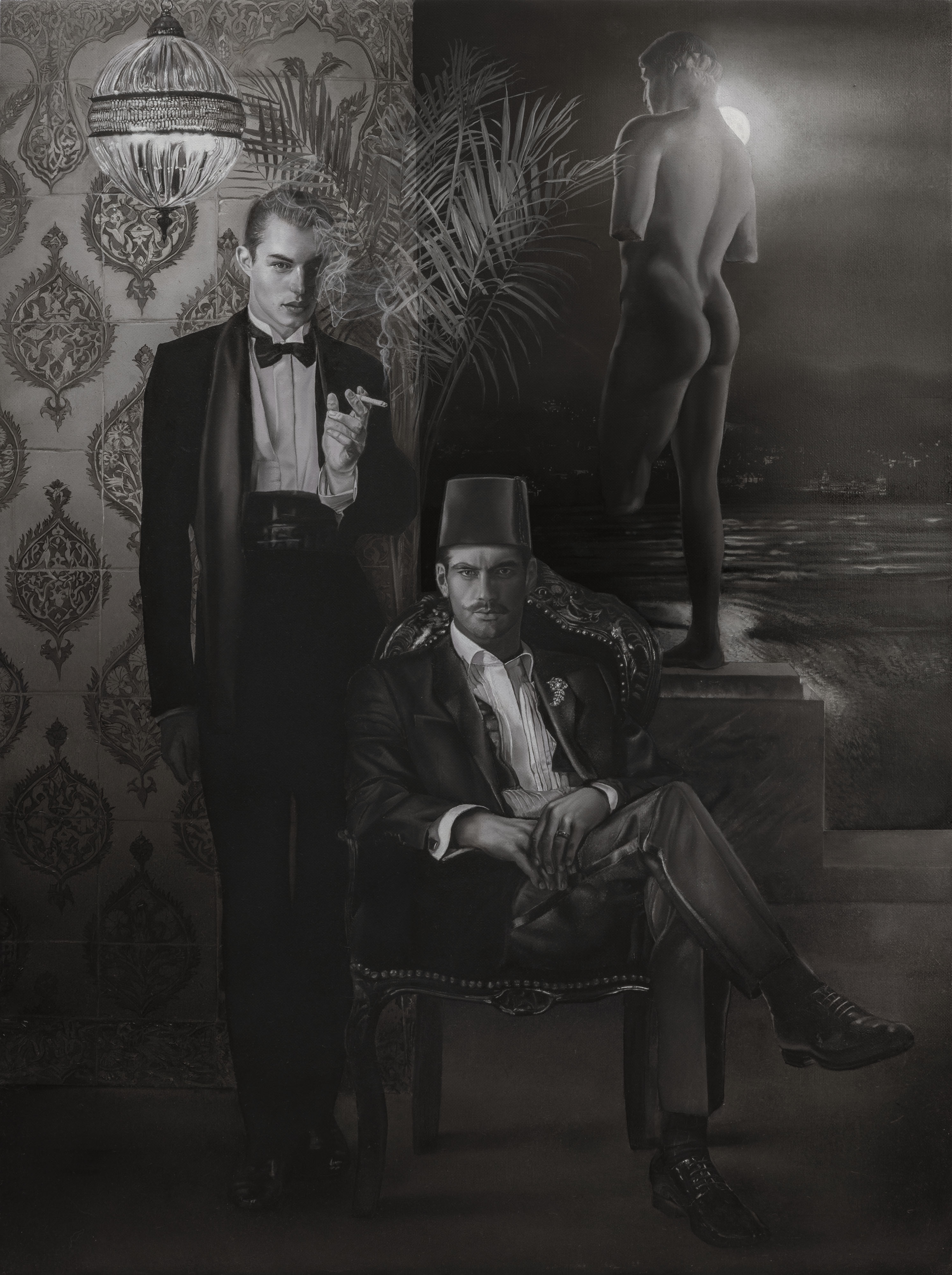

The wall, covered with tiles that have been broken and worn over the years and sloppily reassembled, one on top of another, represents a structure in which Ceylan sees harmony within disharmony. In the artist’s words, it is a wall with a broken heart, both ugly and beautiful, polyphonic and where everything intertwines. Meanwhile, the painting titled Archeology (2023), which Ceylan painted specially for the exhibition, explores a fictional chain of relationships taking place during the Tanzimat era. Entailing the tensions of dichotomies like traditional and modern, East and West, master and slave, this painting reflects different layers of the modernization of the Ottoman Empire. The seated figure with a fez in the middle of the composition alludes to tradition and authority; the young figure standing next to him as a contemporary of the era, and the sculpture illuminated by moonlight recalls the cultural history as well as the future of the geography. The work borrows its title from the Archeology Museum founded in this period under the leadership of Osman Hamdi Bey.

Excerpted from curator Ulya Soley's article in the exhibition catalogue Souvenirs of the Future.

Explore! all the details about the exhibition sections:

Souvenirs of the Future

Memory of Objects

Memory of the Region

Remembering the Future

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)