07 June 2024

How can the future be imagined by looking at a collection or an archive? The lasting quality of ceramics allows us to ponder how the future might be remembered through a ceramics collection, since they render conceivable time eternal. The works produced in scope of the exhibition have the potential to address a collection that holds important clues pertaining to the past with a fresh perspective, taking a step toward remembering the future. The concept of le musée imaginaire (the imaginary museum) that art historian André Malraux proposed during the 1960s points to a collection of artworks existing in the viewer’s mind, a collection that does not physically exist.1 Malraux uses this term to define an ideal museum that can be created by bringing together all the collections of the world. Remembering the future points to a similar theoretical approach: it encourages us to question what souvenirs and collected objects might become.

As Amy Clarke asks in her article, “We’ve been collecting souvenirs for thousands of years. They are valuable cultural artifacts—but what does their future hold?”2Will the changing nature of travel, globalization, mass production, and digital transformation lead to structural changes in the concept of memory? Will postcards continue to exist and be sent? In what ways will the relationships we have with personal objects change while nonbiodegradable materials continue to broaden dump grounds as memories of the environment? As archives and collections are preserved by museums and institutions as guardians of the past, will numerous phenomena transformed into data be enough to provide a field of research, as it does today? These are some of the questions that can guide us as we remember the future.

Postcards usually depict images of ordinary landscapes and assume meaning through the sentimental messages written on them. These touristic communication tools, sent from the visited site to people who are missed or loved, are kept together with letters or objects “associated with a memory.” In the postcards he names Rose Path (2023), Deniz Eroglu ponders the future outcomes of the changes Türkiye is experiencing. Moving forth from the question of what sort of landscape would have been created if the right measures had been taken in economy and urban planning, these visuals offer urban images from the future. Eroglu, who presented a series of works he envisioned as a souvenir shop in his solo exhibition at ARKEN Museum in 2021, addresses the notion of a souvenir from the future in the context of the postcard in Rose Path, which was produced for this exhibition. Roses on a large highway become a part of this landscape, with inspiration from the rose motifs that adorn many objects in the Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics Collection. With its extensive use in art history, foremost as geometric ornament in Islamic art, the rose holds a rather rich scope of associations, considering what it symbolizes religiously and politically as well as its romantic, arabesque connotations. Eroglu’s postcards are accompanied by a fictional story titled “Cities of the Future.”

Videos that comprise Volkan Aslan’s There Was Enough Room Yet No Water (2022) series explore the effects of violence individuals are subject to in everyday life. These videos, in which ceramic trinkets that are often produced as souvenirs—also represented extensively in the museum’s Kütahya Tiles and Ceramics Collection—slowly burn, the destructive, transformative, and disruptive nature of fire makes itself felt but does not grow to the extent that it destroys the bibelots. The fire burning the object recalls destruction as well as the production of ceramics fired at high temperatures. The familiar forms of objects have been estranged: In Walking, a beheaded body of a horse; Huzur, a rose without branches; and The Day After, a bird’s head nestled on a human body. As objects we are accustomed to seeing physically transform into digital and moving images, the neon colors painting the walls render the works timeless.

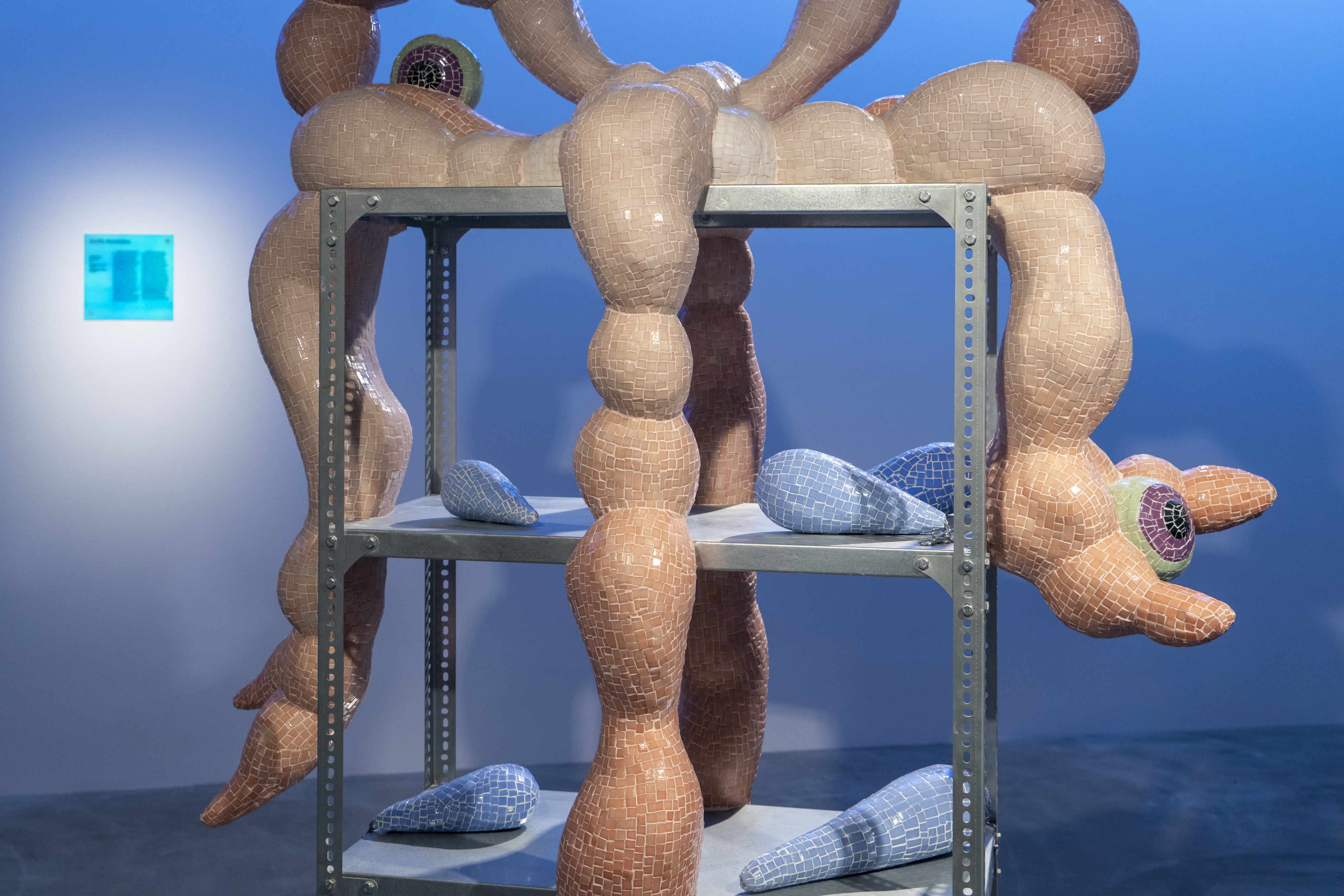

The Present I (2022) is one of the works constituting Zsófia Keresztes’s installation After Dreams: I Dare to Defy the Damage, which she designed for the Hungarian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale. The installation focused on the transitive and complex relationship between the present and the future and explored the effects of this complexity on the construction of identity. In Antal Szerb’s 1937 novel Journey by Moonlight, the protagonist sees the Ravenna mosaics dated to the sixth century on his honeymoon. This cultural heritage evoking admiration encourages him to revisit his own memories. Drawing from the novel, the artist forges a poetic connection between memories and mosaics. Fragments of the past construct the present. The work is placed on a metal shelf system used in storages. While the fluid and undefined structures on the shelves evoke forms from the future, the customary metal shelf and chains do not allow the installation to detach itself from the past. Could The Present I be a structure we will encounter in the collection storage room of a museum bearing a timeless cultural heritage?

Neven Allgeier’s Environment (2019–2023) brings together memories found in landscapes devoid of human presence from the near future. The large photographs in the background are comprised of backdrop images presenting both familiar and foreign elements. It is possible to see human traces in these photographs, but nature prevails to erase them: A pool covered with plants that has changed color over time, tire tracks that have dissolved on soil covered in snow, fallen leaves. These long-empty places suggest a humanless future. As for photographs placed in front of the landscapes, they are memories from the present: plastic bottles in nylon bags, a bird feather that has fallen into the water, a pastel neon plastic chandelier. Each object exists in the context of the landscape it is in. As in the personal stories attached to souvenir objects, these photographs assume new meanings with the viewer’s personal stories.

1. André Malraux, “Museum Without Walls,” Voices of Silence, çev. Stuart Gilbert (Colorado: Paladin Press, 1974), 123.

2. Amy Clarke, “We’ve been collecting souvenirs for thousands of years. They are valuable cultural artifacts – but what does their future hold?” The Conversation, 12 Ekim, 2022.

Excerpted from curator Ulya Soley's article in the exhibition catalogue Souvenirs of the Future.

Explore! all the details about the exhibition sections:

Souvenirs of the Future

Reminiscences of the Motifs

Memory of Objects

Memory of the Region

Tuesday - Saturday 10:00 - 19:00

Friday 10:00 - 22:00

Sunday 12:00 - 18:00

The museum is closed on Mondays.

On Wednesdays, the students can

visit the museum free of admission.

Full ticket: 300 TL

Discounted: 150 TL

Groups: 200 TL (minimum 10 people)